|

You can read this section of the book here on screen, or use the buttons to download it as a PDF or Word file to read on another devise.

|

|

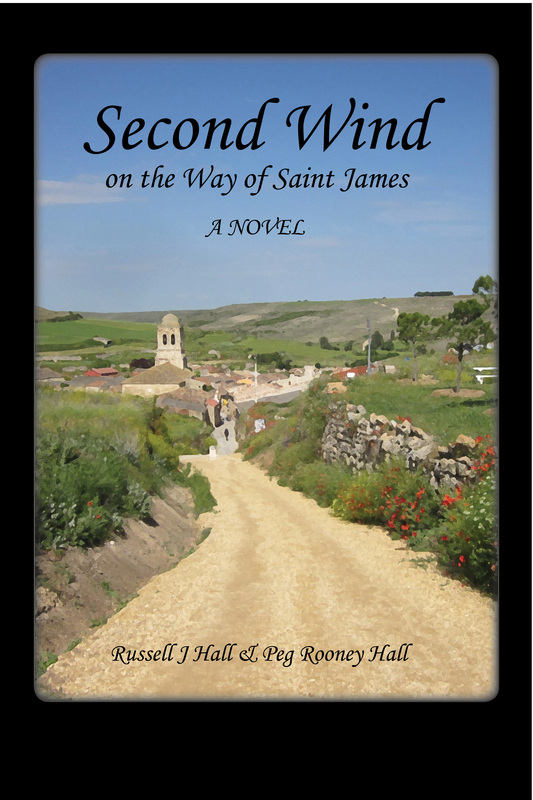

Second Wind on the Way of St. James

© 2013 by Russell J Hall and Peg Rooney Hall Published by: Lighthall Books P.O. Box 357305 Gainesville, Florida 32635-7305 http://www.lighthallbooks.com Orders: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, either electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, except as specified by the authors. Electronic versions made available free of charge are intended for personal use, and may not be offered for sale in any form except by the authors. Excluded from copyright are the maps, which are based on the work of Manfred Zentgraf of Volkach, Germany. Like the original, our adaptations of his map remain in the public domain. Second Wind is a work of fiction. Many experiences of the authors on the Camino have inspired and informed themes of the book, but people and events depicted are products of the authors’ imaginations; any resemblance to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental. |

Episode 6

Stage Six: Secret Lives

Ambasmestas to Samos

Saturday, June 8 to Monday, June 20

Tending the Cemetery

Ambasmestas to O'Cebreiro

Saturday, June 18

Nearing the eighty percent mark toward completion of their long journey, Helen’s confidence that they would make it to Santiago had been growing with almost every step. Of course, any number of calamities could still keep them from getting there, but she felt less vulnerable to the random events that might trip them up. If something happened to thwart them, she was certain its cause would be some external factor, rather than lack of resolve on their part.

Despite this optimism about their journey, the morning found her morose. The trail had begun as a gentle ascent along the roadside path on the far side of town. Now they had turned into the woods. The humidity that was hanging thick had become misty fog. The path was narrow and had grown steadily steeper as they got closer to O’Cebreiro. So much for the feeling of accomplishment!

Also, ever since the steep walk down from the Cruz de Ferro, when she hadn’t been able to get out of her own head, dark thoughts had been bubbling up from her subconscious. And, Bert had seemed distant since the Cruz de Ferro, but she supposed that she had been uncommunicative too, given how weighed down with her thoughts she had been. Try as she might, she couldn’t make them disappear completely.

Yesterday’s fun afternoon of creating the fantasy about Portia and Edith’s friendship had helped, but today the funk was back. Perhaps it was the fog enshrouding the narrow path. If there were scenery out there that might lift the spirits, it was invisible. Not quite rain, they walked through almost-drizzle, and were forced to wear their waterproof jackets. Beads of moisture formed on their eyelashes, and from time to time they needed to brush droplets from their noses.

“You seem down in the dumps,” said Bert. “I know it’s an unusually dreary day, but we’ve seen worse.”

What about you, Bert? The thought came to her instantly, but she didn’t say anything. Instead, noticing his uncharacteristic expression of concern, she responded without challenging him.

“Oh, it’s nothing. I have to agree with all the talk we heard about this walk up to O’Cebreiro being one of the most difficult climbs of the entire Camino, but that isn’t the whole of it. I don’t know; just a mood thing. Maybe it has to do with growing older and my aging body.”

“Well, if it’s about your aging body, I suppose I can’t help. I might try to think of a cheerful tale to tell. Hmm, at the moment none comes to mind. We probably just need to slog along until the sun throws a new light on things.”

It did seem to be a mood thing because Helen felt an alarming sense of unease—as if she were being whipsawed emotionally. She would settle her mind on less troubling things, and then without warning the unsettling ones would well up again.

She couldn’t quite imagine that it would bring relief, but she found herself wanting to talk to Bert about it. She really wasn’t looking for his help, as much as for him to be willing to listen and understand. She knew she couldn’t explain it to him, but if they talked around the edges of the problem, he might fortuitously hit on a mood-changer.

There had been a time when she thought that, with the right person, she could talk openly and honestly about the real her. It was a silly idea. She had tried putting her trust in Greg, and it had been a mistake. Since Greg, she’d never trusted anyone to get that close again.

Once she had stepped to the brink with Bert, then panicked and backed off far and fast. Why should she expect him to be any different, she’d thought at the time.

But here on the Camino she felt safer than any place she had been, maybe ever. And, for heaven’s sake, she thought, I sure as heck ought to have better judgment at this age about who I can trust than I did back then.

They trudged along, watching their feet so as to avoid stumbling over rocks and roots as they climbed the shrouded, slippery path. There was unlikely to be a better time to reach out, she realized. They were already in a down mood, so it wasn’t as if she would be ruining anything.

“This is really silly, Bert, but bear with me. Ever since the day we watched those two men at Cruz de Ferro my subconscious has been raising narratives in my head that have left me puzzled and disconcerted. Maybe our conversations about Mr. and Mrs. Lovebird were part of it too.”

“Honestly, Helen, I am sorry about what I said that night . . .”

“Really, it’s not about that. It’s something else entirely. I don’t know. The Camino is supposed to help you soar above all that baggage you carry around, but from what I can tell, spending so much time thinking isn’t a healthy thing.”

“Okay, I’m intrigued. Pray tell, what unhealthful things have been rattling around in your cranium.” He looked over at her, smiling slightly as he huffed and puffed up the hill.

“Oh, I guess it really was silly. Never mind. Trust me, you don’t want to know. Besides, I don’t want to tell you, and I’m not about to.”

His smile evaporated, and he looked away. She could tell that he heard her and understood that she wasn’t about to share any secrets with him. On second thought, she feared that her statement had been overly dismissive and off-putting.

“Okay, I’ll give you one example—a trivial one. It happened . . . I can’t remember exactly when. It was sometime a while ago when you were walking ahead. I fell in with three Czechs, two young men and a woman. They were very nice. They eventually forged ahead, and maybe you saw them. They had to have passed you. They were really quite friendly. They all seemed to speak some English, but one of the men was very good and very talkative. He and I bantered on, I suppose for a half mile or so.”

“I’m afraid I left my psychoanalyst license back in the U. S., but I’m all ears, so keep going.”

“Well, I said something about his good English. I asked if he was planning to go abroad to work. I mentioned that Polish man we met who was looking for a job in the UK. The Czech said, no, he would be staying at home, in the little village in Moravia where he grew up. You’d never guess why. He said because everybody else in his family had moved away. Someone had to stay behind and take care of the cemetery. He said that’s the Czech way. Most of his countrymen felt like he did. Whether they actually stayed or not, they thought it was the right thing to do.”

“Okay, I agree I never heard of staying home to take care of the cemetery before,” said Bert. “But what’s so disturbing about that, and what’s it got to do with you? Have you been hiding a cemetery somewhere you want to take care of?”

She ignored his questions.

“There was another incident also. When we were coming down from Acebo, a hiker startled me, coming up behind me. And when I looked back, for a split second, I thought it was my dad. I know, I know. Too weird. But it may be part of my angst because when I heard the Czech’s story, what plagued me first were thoughts about my two fathers.”

“Helen, other people have reported experiences like yours, and in fact, I think it’s fairly common. I suppose some might find it depressing, but it strikes me that it could just as easily be a happy and even comforting event. Anything else?”

“Not really, and I don’t know what your problem is. Why are you expecting me to provide you with more information? Maybe you did bring along your imaginary psychotherapist’s license, and you want me to say something that will give you an opportunity for a little practice.”

“Sorry, Helen. You’re the one who started this conversation, and I thought there might be something you wanted me to help you with.”

“Okay, Doctor Freud, you are looking for connections, so here’s one. I had two fathers, and they’re both in cemeteries somewhere. How about that?”

“And the men you saw at the Cruz de Ferro . . . and the Lovebirds . . . how do they fit in?”

“I don’t know, Bert, and it really bothers me. I don’t think there is a connection. As you well know, I was fond of the father who raised me, but I never met the one who left when I was a baby, so there can’t be much of a connection between the two of them. Except . . .maybe, deep down in my kid thinking . . .I feared my parents, especially my dad, would leave me too if I gave them any hint of a reason."

"Wait, Helen, stop a minute," Bert said reaching over and putting his hand on her arm. "That's a dreadful thing for a kid to have to deal with. It sure is harder to be a child than it seems it ought to be,” he said unusually gently.

“Thanks, Bert. Let’s keep walking, even though my foot is beginning to hurt. Let’s hope O’Cebreiro is just beyond that next turn up there and a hot toddy is waiting for us.”

“Definitely a good thought. Are you going to keep talking?”

“Must I? Well, okay. That whole cemetery thing with the Czechs got me thinking about my birth father. It struck me that he was always frozen in time to me. I never thought of him in terms of birth date and death date. It just dawned on me after talking to the Czechs about tending the cemetery that he was only about twenty-one when he left me. Then I got thinking about decisions I made in my twenties. Maybe I should have been cutting him some more slack all these years―been more understanding of the position he was in.”

They’d gotten beyond that next bend. O’Cebreiro wasn’t there yet, but the misty rain stopped and the trail widened. It was open on the right to green pasture land. The dirt was firm underfoot here where the moisture was not held in by trees on both sides. The potato-size stones that had littered the path disappeared and the overcast was lifting. They talked as they walked side by side, occasionally stopping to catch their breath and enjoy the views.

“The trail sure is nicer up here. Look, up ahead. Those farmers seem to have just released that colt into the pasture,” noted Bert.

Helen talked on. “Somehow the chat about cemeteries makes me think something is missing in my life. I know that some people visit cemeteries, but I’ve never done it. Maybe I should try sometime—put it on my bucket list. Not only do I not visit cemeteries, I don’t know of anybody who would visit my grave, if perchance my earthly remains were to wind up in a cemetery. I can’t think about anybody who would do something quirky like that, with the possible exception of you. My sisters would probably attend a memorial service, but I can’t see them fussing around about a tombstone.”

“No wonder you’ve been so pensive lately. Cemeteries, memorial services, mourners; can you think of any more gloomy subjects? More than the weather or age was feeding your somber mood. It’s bizarre. Also, this new-found obsession with cemeteries isn’t like you at all.”

They were next to each other on the trail. He reached over, letting his stick hang on his wrist, and took her gently by the arm. They stopped.

“Wait, I think I have an explanation,” he said. “I hadn’t thought of it before, and the word bizarre again comes to mind. This whole pilgrimage has us walking toward a cemetery—the resting place of Saint James. Or his bones, at least. One idea for where the word compostela comes from is compost terra, Latin for cemetery. I think that’s it! What do you think?”

Helen had to laugh. That was classic Bert. All cerebral. And back to normal from his gingerly emotional reactions. She liked his classic cerebral self, but she could come to really like his occasional reaching out to her from the heart.

The Camino ended the conversation. The sun broke through, or maybe it was that their climb had lifted them above the clouds. Whatever the cause, the landscape was now a panorama bathed in patches of gold and silvery glow.

“Look, there’s an eagle. I don’t know what kind, but I’m pretty sure it’s an eagle.

“How can you say that, Bert? Isn’t it as clear as the socks hanging from your backpack that what you see is a vulture attracted to us by my deathly stupid conversation?”

They shared a laugh, and continued up the trail.

Maybe it was the sun’s warm glow. Maybe it was the sharing and unburdening. Regardless, Helen felt better. The mood had passed. That was good. She was pleased and hoped it would last, but was also a bit uncomfortable. She hoped Bert wouldn’t read too much into what she had said.

Despite this optimism about their journey, the morning found her morose. The trail had begun as a gentle ascent along the roadside path on the far side of town. Now they had turned into the woods. The humidity that was hanging thick had become misty fog. The path was narrow and had grown steadily steeper as they got closer to O’Cebreiro. So much for the feeling of accomplishment!

Also, ever since the steep walk down from the Cruz de Ferro, when she hadn’t been able to get out of her own head, dark thoughts had been bubbling up from her subconscious. And, Bert had seemed distant since the Cruz de Ferro, but she supposed that she had been uncommunicative too, given how weighed down with her thoughts she had been. Try as she might, she couldn’t make them disappear completely.

Yesterday’s fun afternoon of creating the fantasy about Portia and Edith’s friendship had helped, but today the funk was back. Perhaps it was the fog enshrouding the narrow path. If there were scenery out there that might lift the spirits, it was invisible. Not quite rain, they walked through almost-drizzle, and were forced to wear their waterproof jackets. Beads of moisture formed on their eyelashes, and from time to time they needed to brush droplets from their noses.

“You seem down in the dumps,” said Bert. “I know it’s an unusually dreary day, but we’ve seen worse.”

What about you, Bert? The thought came to her instantly, but she didn’t say anything. Instead, noticing his uncharacteristic expression of concern, she responded without challenging him.

“Oh, it’s nothing. I have to agree with all the talk we heard about this walk up to O’Cebreiro being one of the most difficult climbs of the entire Camino, but that isn’t the whole of it. I don’t know; just a mood thing. Maybe it has to do with growing older and my aging body.”

“Well, if it’s about your aging body, I suppose I can’t help. I might try to think of a cheerful tale to tell. Hmm, at the moment none comes to mind. We probably just need to slog along until the sun throws a new light on things.”

It did seem to be a mood thing because Helen felt an alarming sense of unease—as if she were being whipsawed emotionally. She would settle her mind on less troubling things, and then without warning the unsettling ones would well up again.

She couldn’t quite imagine that it would bring relief, but she found herself wanting to talk to Bert about it. She really wasn’t looking for his help, as much as for him to be willing to listen and understand. She knew she couldn’t explain it to him, but if they talked around the edges of the problem, he might fortuitously hit on a mood-changer.

There had been a time when she thought that, with the right person, she could talk openly and honestly about the real her. It was a silly idea. She had tried putting her trust in Greg, and it had been a mistake. Since Greg, she’d never trusted anyone to get that close again.

Once she had stepped to the brink with Bert, then panicked and backed off far and fast. Why should she expect him to be any different, she’d thought at the time.

But here on the Camino she felt safer than any place she had been, maybe ever. And, for heaven’s sake, she thought, I sure as heck ought to have better judgment at this age about who I can trust than I did back then.

They trudged along, watching their feet so as to avoid stumbling over rocks and roots as they climbed the shrouded, slippery path. There was unlikely to be a better time to reach out, she realized. They were already in a down mood, so it wasn’t as if she would be ruining anything.

“This is really silly, Bert, but bear with me. Ever since the day we watched those two men at Cruz de Ferro my subconscious has been raising narratives in my head that have left me puzzled and disconcerted. Maybe our conversations about Mr. and Mrs. Lovebird were part of it too.”

“Honestly, Helen, I am sorry about what I said that night . . .”

“Really, it’s not about that. It’s something else entirely. I don’t know. The Camino is supposed to help you soar above all that baggage you carry around, but from what I can tell, spending so much time thinking isn’t a healthy thing.”

“Okay, I’m intrigued. Pray tell, what unhealthful things have been rattling around in your cranium.” He looked over at her, smiling slightly as he huffed and puffed up the hill.

“Oh, I guess it really was silly. Never mind. Trust me, you don’t want to know. Besides, I don’t want to tell you, and I’m not about to.”

His smile evaporated, and he looked away. She could tell that he heard her and understood that she wasn’t about to share any secrets with him. On second thought, she feared that her statement had been overly dismissive and off-putting.

“Okay, I’ll give you one example—a trivial one. It happened . . . I can’t remember exactly when. It was sometime a while ago when you were walking ahead. I fell in with three Czechs, two young men and a woman. They were very nice. They eventually forged ahead, and maybe you saw them. They had to have passed you. They were really quite friendly. They all seemed to speak some English, but one of the men was very good and very talkative. He and I bantered on, I suppose for a half mile or so.”

“I’m afraid I left my psychoanalyst license back in the U. S., but I’m all ears, so keep going.”

“Well, I said something about his good English. I asked if he was planning to go abroad to work. I mentioned that Polish man we met who was looking for a job in the UK. The Czech said, no, he would be staying at home, in the little village in Moravia where he grew up. You’d never guess why. He said because everybody else in his family had moved away. Someone had to stay behind and take care of the cemetery. He said that’s the Czech way. Most of his countrymen felt like he did. Whether they actually stayed or not, they thought it was the right thing to do.”

“Okay, I agree I never heard of staying home to take care of the cemetery before,” said Bert. “But what’s so disturbing about that, and what’s it got to do with you? Have you been hiding a cemetery somewhere you want to take care of?”

She ignored his questions.

“There was another incident also. When we were coming down from Acebo, a hiker startled me, coming up behind me. And when I looked back, for a split second, I thought it was my dad. I know, I know. Too weird. But it may be part of my angst because when I heard the Czech’s story, what plagued me first were thoughts about my two fathers.”

“Helen, other people have reported experiences like yours, and in fact, I think it’s fairly common. I suppose some might find it depressing, but it strikes me that it could just as easily be a happy and even comforting event. Anything else?”

“Not really, and I don’t know what your problem is. Why are you expecting me to provide you with more information? Maybe you did bring along your imaginary psychotherapist’s license, and you want me to say something that will give you an opportunity for a little practice.”

“Sorry, Helen. You’re the one who started this conversation, and I thought there might be something you wanted me to help you with.”

“Okay, Doctor Freud, you are looking for connections, so here’s one. I had two fathers, and they’re both in cemeteries somewhere. How about that?”

“And the men you saw at the Cruz de Ferro . . . and the Lovebirds . . . how do they fit in?”

“I don’t know, Bert, and it really bothers me. I don’t think there is a connection. As you well know, I was fond of the father who raised me, but I never met the one who left when I was a baby, so there can’t be much of a connection between the two of them. Except . . .maybe, deep down in my kid thinking . . .I feared my parents, especially my dad, would leave me too if I gave them any hint of a reason."

"Wait, Helen, stop a minute," Bert said reaching over and putting his hand on her arm. "That's a dreadful thing for a kid to have to deal with. It sure is harder to be a child than it seems it ought to be,” he said unusually gently.

“Thanks, Bert. Let’s keep walking, even though my foot is beginning to hurt. Let’s hope O’Cebreiro is just beyond that next turn up there and a hot toddy is waiting for us.”

“Definitely a good thought. Are you going to keep talking?”

“Must I? Well, okay. That whole cemetery thing with the Czechs got me thinking about my birth father. It struck me that he was always frozen in time to me. I never thought of him in terms of birth date and death date. It just dawned on me after talking to the Czechs about tending the cemetery that he was only about twenty-one when he left me. Then I got thinking about decisions I made in my twenties. Maybe I should have been cutting him some more slack all these years―been more understanding of the position he was in.”

They’d gotten beyond that next bend. O’Cebreiro wasn’t there yet, but the misty rain stopped and the trail widened. It was open on the right to green pasture land. The dirt was firm underfoot here where the moisture was not held in by trees on both sides. The potato-size stones that had littered the path disappeared and the overcast was lifting. They talked as they walked side by side, occasionally stopping to catch their breath and enjoy the views.

“The trail sure is nicer up here. Look, up ahead. Those farmers seem to have just released that colt into the pasture,” noted Bert.

Helen talked on. “Somehow the chat about cemeteries makes me think something is missing in my life. I know that some people visit cemeteries, but I’ve never done it. Maybe I should try sometime—put it on my bucket list. Not only do I not visit cemeteries, I don’t know of anybody who would visit my grave, if perchance my earthly remains were to wind up in a cemetery. I can’t think about anybody who would do something quirky like that, with the possible exception of you. My sisters would probably attend a memorial service, but I can’t see them fussing around about a tombstone.”

“No wonder you’ve been so pensive lately. Cemeteries, memorial services, mourners; can you think of any more gloomy subjects? More than the weather or age was feeding your somber mood. It’s bizarre. Also, this new-found obsession with cemeteries isn’t like you at all.”

They were next to each other on the trail. He reached over, letting his stick hang on his wrist, and took her gently by the arm. They stopped.

“Wait, I think I have an explanation,” he said. “I hadn’t thought of it before, and the word bizarre again comes to mind. This whole pilgrimage has us walking toward a cemetery—the resting place of Saint James. Or his bones, at least. One idea for where the word compostela comes from is compost terra, Latin for cemetery. I think that’s it! What do you think?”

Helen had to laugh. That was classic Bert. All cerebral. And back to normal from his gingerly emotional reactions. She liked his classic cerebral self, but she could come to really like his occasional reaching out to her from the heart.

The Camino ended the conversation. The sun broke through, or maybe it was that their climb had lifted them above the clouds. Whatever the cause, the landscape was now a panorama bathed in patches of gold and silvery glow.

“Look, there’s an eagle. I don’t know what kind, but I’m pretty sure it’s an eagle.

“How can you say that, Bert? Isn’t it as clear as the socks hanging from your backpack that what you see is a vulture attracted to us by my deathly stupid conversation?”

They shared a laugh, and continued up the trail.

Maybe it was the sun’s warm glow. Maybe it was the sharing and unburdening. Regardless, Helen felt better. The mood had passed. That was good. She was pleased and hoped it would last, but was also a bit uncomfortable. She hoped Bert wouldn’t read too much into what she had said.

Bert's Secret

O'Cebreiro, and on to Triacastela

Saturday, June 18 and Sunday, June 19

The woods closed in on both sides of the trail again as they climbed another steep ascent. And then, abruptly, they were at the top and there they were, in O’Cebreiro. Bert felt exhausted as he always did when they arrived at their day’s destination. In fact, today’s climb had been so demanding that for the past half hour or so he thought he couldn’t get more tired. But when they stepped out of the woods onto the paved road and saw the town smack in front of them, an additional heavy layer of exhaustion poured in like a tidal wave.

Lately new little aches, pains, and weaknesses had made themselves known. The left knee, which had given out once and threatened to do it again, was perhaps a bit more on the brink than in days past. One toe tended to get numb after a few hours of walking, and he could restore it partly only after vigorous wiggling of all his toes. Also, a pain in his right hip visited him not when walking, but afterwards, when resting. It made sitting uncomfortable, and occasionally almost unbearable. And, of course, the twisted ankle could not be ignored. By this point in their adventure, it seemed clear to him that walking twelve miles in a day was something qualitatively different from walking twelve miles several days in a row. And walking twelve miles a day for several weeks was something else again.

This was a funny day. The surprising wave of additional tiredness at the end fit the rest of it. They started on the steep and challenging trail in weather as gloomy as Helen’s mood. They ended the walk in bright sunshine in this lovely little village on top of the mountain. Looking back at the path from which they’d just emerged, they saw that the patch of woods embracing it was narrow. Just to their left, along the shoulder of the road was a wide stone wall topped with flat field stones. They sat, gazing and enjoying the respite. The views, back down to the valley where they began and across it to cloud-topped mountains, were spectacular.

Bert thought about how the early fog and drizzle, the heavy air, and the grueling initial ascent with no clear vistas to reward them, had led him to pondering his aches and pains.

Ever since La Cruz de Ferro, it weighed heavily on him that maybe Helen couldn’t be a part of the new life he had to make for himself. He had been shaken out of his mood by Helen’s reserved but uncharacteristically candid sharing of her thoughts and talk about cemeteries. What a strange conversation! It was so clear that she had been really upset thinking about her dad and her father, as she called them. He hoped he hadn’t said anything he shouldn’t have. The universe must have created this day for borderline craziness. Somewhere in it was the germ of a hope that Helen might be willing to look to a new future also.

Here on top of the mountain, the air around them felt different. What had changed? Was it the day, the Camino, Helen’s revelations? Had the nature of their friendship shifted? What made their closeness feel more cordial, more relaxed? Could he believe that anything, in fact, had changed?

Whatever the reason, now it was he who was wanting to talk about things he had never revealed before. He didn’t know how it would happen, but he knew when he did, it was Helen he wanted to tell.

They checked into their casa rural, more upscale than their usual albergues. They not only had a private room, but a private bath also. They showered and washed their wet, muddy clothes. The routine of arriving and cleaning up had rejuvenated him. It was still early afternoon. Hungry, they found a rustic restaurant with stone walls, hand-hewed beams, apparent locally made sausages hanging over the bar and, and a roaring wood fire. They grabbed a table next to a window looking out over the distant mountains.

Encouraged by her sharing earlier, over an overpriced bowl of caldo gallego, a rich stew of local vegetables and meat, and a glass of beer, as a tentative first step, Bert ventured a bit of sharing of his own.

“Your bringing up the subject of cemeteries called back to mind an incident from my childhood that also involved one, in a way.”

“It is my turn to be all ears,” Helen said. “I hope I’ll be as good a listener as you were, and that your story won’t be quite as nutty as mine. I wish they’d close the door. It’s drafty in here.”

“No promises, but okay, here it is. When I was about eleven or twelve, my father let me come along one time when his group of amateur archaeologists went on a field trip. He must have been stuck with me for the day for some reason because he had never brought me along before and never did again. The group was exploring a Paleoindian site, and one of the men discovered a human bone sticking out of the ground.”

“Oh my, that sounds both creepy and thrilling.”

“I felt like I was in a movie or something to have that happen when I was there. While all the grownups were talking about it and ignoring me, I took a photo of it—with my Brownie Special.”

“Oh, my gosh. I had one of those too. I thought it was so great that I got a camera of my own, and my sisters were too young. Sorry to interrupt. Go on with the tale!”

“Well, of course, my father and the men left the bones undisturbed and later reported the find to whomever. Ultimately my father told me the bones were turned over to a local Indian tribe.”

“Did you tell your father about the photo?”

“Oddly, I never even considered telling him. I was pretty independent, as you’ve noted before. Your question is pertinent though because the tribe announced that no artifacts could be taken from the site, and no photographs.”

“Artifacts I can understand. But photos?”

“I remember being frightened about having the photo. I didn’t believe in ghosts, but imagined the ghost of that Indian seeping into my room at night. Still, I wasn’t about to give it up. So I compromised with myself. I destroyed the photograph, but kept the negative. At the time it felt like I had a little victory, a little bit of growing up. I’d overcome my fear. It all seemed silly after I became an adult, but I still have the negative. And to this moment I have always kept it a secret.”

“Well, Bert, I love the story. Around the office, you have a reputation for being a by-the-books kind of guy. But I have always felt you followed only the rules that made sense to you. Now I see that you were like that way back when you were just a kid. It makes me feel like I have known you even longer than I have. Maybe if I think about it awhile, I’ll even figure out your conflicted attitude toward the Camino.”

“Perhaps that’s enough about bones for a while though. Let’s go explore the village.”

“I’m ready. The soup and beer will hold me until dinner hour.”

Bert felt good as they got up and paid their bill. Telling Helen his long and closely held secret was a vaguely emotional and surprisingly pleasant experience. He found himself thinking he might try it again sometime. She hadn’t reacted negatively, and even seemed to have enjoyed it. He had a bigger secret that weighed on him, and sometime she might learn about that one too.

________________

An opportunity came that very evening. They were drinking wine in the restaurant at their casa rural, finishing off the bottle that had come with their dinner. They were both relaxed and mellow. It seemed like he probably ought to grab the momentum.

He hadn’t gotten over his reticence to talk to her about things he thought of as private, and talking about the photo had been difficult for him. But it hadn’t turned out badly. He wasn’t as embarrassed as he expected; he didn’t feel stupid. He was relieved that she had taken him seriously. Her insights about his relationship with the rules and expectations were a total surprise—probably right on the mark, he thought.

She had opened the gates by sharing her concerns earlier. He thought of her as much less willing to share than he—and he was Fort Knox.

But, then he had second thoughts. This was probably not the right time to talk about the second secret. It would be too much pushing their envelope all in one day. They had plenty of days left on the Camino. If it seemed like a good idea later on, he would reconsider.

His big secret wasn’t damning, at least not in the usual literal sense. And it wasn’t the kind of thing most people would keep wholly to themselves. Nevertheless, it was a heavy burden on him. Why, he wondered, had it been like that it all these years? Like keeping that old negative, he wished he’d known the Cruz de Ferro tradition earlier. He would have tied them both to a stone and kissed them goodbye.

Since the Cruz de Ferro he had spent a lot of time, in what he had come to think of as his walking mind, with thoughts that seldom rose to his consciousness and even less frequently were allowed to stay there. The core of an answer to the question he usually ignored so assertively had begun to come to him. But he wasn’t there yet.

He now suspected that Helen may have had similar experiences of self-recognition. If he shared his secret with her, she might have an insight like she did about his relationship with rules. She might be able to help him to fill in the parts he was still missing. He liked her comment about feeling like she’d known him since he was a boy. But what if, this time, her comment wasn’t comforting?

Of course, that was the real problem; and that was why he was hesitating. Where would it end? It was why he wasn’t too upset when she pulled away that weekend after their divorces. In truth, he hadn’t been any more ready than she to try again. Once you start sharing, each secret might be more painful than the last. He wasn’t quite ready to begin filling in all the missing parts of himself.

On the other hand, maybe that’s what the Camino and that Cruz de Ferro message are all about. Bert ordered a second bottle of wine for them. The genie was getting out of the bottle. He decided this would be as good a time as any. He steeled himself.

“There’s something about me that you don’t know,” he said. “It’s another long-kept secret, and it’s been bothering me for the past few days, like the concerns you shared with me earlier. Your reaction to my photo story has nudged me to share this one as well.”

“Okay,” she said. “I might be more worried about what you are going to say except that I found the photo story to be so interesting. And I liked what it told me about you.”

“Actually, this has been bothering me for years, so why should I be talking about it now? I suppose it’s the Camino. Walking has gotten me thinking about it and wanting to tell you. Anyway, I don’t feel like we can be real friends unless you know. So here goes.”

“Hello.” Through the room came Jacques and Hélène, a couple they had spoken with while having a café con leche at a bar along the trail a few days ago.

“Hold that thought,” whispered Helen.

“Damnation,” responded Bert.

Burley, gray-bearded Jacques, still in shorts despite the mountain cold, and pale, slight Hélène with her plastic-framed glasses—Helen’s almost namesake—came over to the table and joined Bert and Helen. Bert hid his frustration well, but Helen gave him a knowing smile. The four of them compared notes about the relative values of their respective dinners. The Canadians had dined across the street at another restaurant and were just returning to the casa rural.

“Where are you staying tomorrow? Maybe we could meet and see the sights together.”

They quickly ascertained that they were planning to walk to different destinations—the Canadians were stronger walkers—and after expressions of regret, they bid their farewells.

Helen’s interested eyes gave Bert the clear go ahead to resume his monologue at the point where they had been interrupted.

“As I was about to say, you had every reason to think that I had a more or less normal background. Coming up, that is, just a normal American childhood, nothing special. In fact, one thing was different. You see, I graduated from college at age nineteen, and got a PhD at age twenty-three, even though I tried to slow things down as best I could. So, there you have it.”

He waited for what seemed a very long time, expecting a gasp. Or what? He didn’t know what to expect.

“Bert! That’s no deep, dark secret. Why, I thought you were going to tell me you were a convicted criminal or had a rare genetic disorder that would rapidly bring on psychosis as you approach your sixties. Why would the fact that you’re a quick study be something to keep hidden?”

“You don’t understand. When this is happening I’m in my early twenties, I am—as you say—a quick study, and everyone around me thinks I’m a prodigy. It wasn’t so much my parents—they wanted me to go into business management. It was others, especially teachers, and along with them, it was me too. I came to believe that I had truly extraordinary talents. It was my destiny to become a great scientist.”

“And you never did.”

“No, barely twenty-three years old, I was too young to be a professor. Some of my fellow graduates, who were mostly about a decade older than me, went on to postdoctoral programs in order to sharpen their skills and better qualify for academic positions. I didn’t want to do that. I thought I was tired and needed a break. Actually there was something else. It was hubris I guess. I didn’t think I needed a postdoc. I was ready to launch into the real world, and no additional tune-up was required. I thanked my professors for suggesting a postdoc, but I didn’t believe my scientific credentials needed to be enhanced.”

“How did you wind up in the Fish and Wildlife Service?”

“Well, Fish and Wildlife was willing to hire me, even at my tender age, and I felt the organization was doing good work, had a great need for good science, and could benefit from my super sharp scientific skills. Plus, it was a way to get a taste of the real world before I returned to academia.

“As things turned out, and as you know, the Service did have a great need for good science, but I eventually learned it wasn’t the kind I had earlier excelled at. Fish and Wildlife Service science was no better or no worse than academic science, but it wasn’t the arena where a prodigy could make much of a difference.

“I stayed on, and after a few years my academic credentials had dimmed. I sensed it was already too late to go back to academe. I felt I was doing important work with Fish and Wildlife, but I was no longer riding the crest of the wave. By the advanced age of thirty, still younger than most of the folks who got their PhDs with me, it was clear that I had failed to achieve my destiny. There was nothing else. No mountains to climb. No chance for greatness.”

“So you were doing important work, but not working at the level of excellence you expected of yourself. Is that what you’re saying?”

“At first I didn’t want to reveal my years as a prodigy because I didn’t want my colleagues to view me as something different. I didn’t even tell people I had a doctorate. I didn’t want to be an odd duck. As time went on, my reluctance to tell people became no longer the desire to appear normal to my co-workers. Instead, it was the failure and waste of it all and the accompanying embarrassment that bothered me. That—my failure—was what I was reluctant to reveal to others. At some level I have long realized that my failure is a heavy burden on me, but it wasn’t until walking on the Camino that I began to fully get my secret out into the conscious regions of my mind. My burden is that I had a great opportunity, and I let it go down the drain.”

Helen seemed anxious to set the conversation on a better course. “Bert, I’m glad you told me. Odd, isn’t it, how things we have kept completely to ourselves are so painful to share. First of all, it’s horrible carrying around such a burden for so long. Then telling someone else about it, just saying it out loud, brings back the agony that made you keep it a secret.

“I think I can see how you must feel about failing to stay on the crest of your early accomplishments, but I have to tell you I don’t believe in destinies. At some point as a teenager, I thought I would become the nucleus of a family with a loving husband and four wonderful children. Of course it didn’t happen, it can’t happen, and despite what I thought as an eighteen-year-old, it never was my destiny. In fact, right now my destiny is Santiago. Actually I believe my destiny is unknown, but nevertheless is something I can partially control, or at least influence.”

She appeared to be gathering her thoughts. She stared into a little lantern on the table, seeming to seek light from its flickering candle. The room was dark, and the candle’s reflection in her eyes gave them an emerald cast that he’d never noticed before.

“Bert, you were little more than a teenager. You had gotten positive feedback from everyone around you, and had come to believe all the nice things people said about you. Who wouldn’t? And now you’re second-guessing a decision you made thirty years ago. You’re being much too hard on yourself. And don’t you think if becoming a great scientist really was your destiny, it would have happened somehow? Could something as trivial as taking a job after graduate school have derailed a destiny engraved in the annals of the universe? Maybe I’m repeating myself, but you are a good friend and I hate to see you walk around in a prison you’ve built for yourself.”

Was she scolding him? Of course not. Why wasn’t he feeling much of anything? Her way of seeing his decision to join Fish and Wildlife and his sense of having failed to achieve what he was supposed to, given his talents, was a new way of thinking about that time in his life. Maybe she had it right, but the conclusion was too different for him to go there yet. He needed to think about it more. He would do that, but not just yet.

Something had stuck in his mind, however, and he couldn’t let it go.

“I know this discussion has been about me,” he said, “but what you said about your destiny . . . what you once thought was your destiny that never materialized . . . is too important to let just float by. You have told me more than once that you have no regrets about your decision to get a divorce. I think I still believe you, but what you just said was different—the part about a loving husband and four children. I suspect you may have regretted missing that part of your life from time to time.”

“You may be right. Yeah, there could be something there. By the way, the wine is gone.”

“Yes, and I’m really tired. It’s been a long day.”

“Me too.”

“Let’s see what tomorrow brings.”

He didn’t know what to think. He didn’t feel like he was saving his life, but could it be that he might help Helen to save hers?

____________

The next morning as they had loaded up their gear and headed down the stone pavement, Bert was still ready to talk.

“Our conversation from last night got me thinking—thinking so much that I didn’t do too much sleeping. But that’s okay. I don’t mind the lack of sleep.”

“I hope nothing I said made you toss and turn all night. Good thing we weren’t in a crowded albergue.”

“Oh, no. I don’t even know which one of us said it. Maybe both of us did. But the word failure came up, and we both recognized that I had been carrying around a sense of failure because I hadn’t lived up to expectations, and it wasn’t anybody else’s, but just my own expectations of myself.”

“I don’t remember either who said it first.”

“Our little talk got me thinking about my other failures, and made me realize I need to come to grips with them too. There’s the matter of my failed marriage. You have nothing to do with that, and I’ll tackle dealing with that one on my own. The question is whether I will let that failure—and make no mistake, there was failure on my side as well as hers—will I let it take charge of my future life and determine what I will and will not try to do? So, even though I won’t drag you into that one, there is one where you can probably help because you’re knowledgeable and have some relevant experience. That one has to do with my career.”

“We’ve been giving each other career counseling for years in our informal, gossipy sort of way,” said Helen.

“I don’t expect any answers or solutions from you, but I do want to share my feelings with you, just so you know where things lie. And maybe someday, a situation will come up in which you have a key bit of advice to offer.”

He retraced the times in their careers when they had worked together in reasonable contentment. Then she had made the critical move that put her career on an upward and rewarding track while he remained behind and suffered a series of disappointments. His recommendations on protections needed for several endangered species had been cast aside in the face of what he regarded as political expediency.

On a seeming tailspin, his career appeared bound for a crash. But it had been rescued by a temporary promotion to a position where he performed competently. The promotion became permanent, and he expected to continue in it or a similar post until retirement. It didn’t really make him happy, but it was better than before.

His health intervened, however, and then came the task force. This was as close to being happy at work as he’d been since she’d left for the Florida job.

Helen knew all of this, but she let him go on so she could get some sense of how it affected him. Could he ever be happy with his work? She cut him off.

“Bert, I know what you are going to say, and you needn’t tell me, because I’m way ahead of you. I really am. I’m way ahead of you.”

He looked shocked by the interruption, but waited for her to say what she wanted to.

“You have the answer, Bert. You have it yourself, and you just don’t know how to use it!”

She stopped and pulled him to the side of the trail, where they could talk face to face. Her words were soft and measured. “Remember our discussion back in Estella, I think it was Estella, where you had talked to that man and had gotten curious about people’s motivations. It was about poorness in spirit, and your cousin, and how maybe she thought happiness would forever be beyond her reach. You joked about a poorness-in-spirit gene. I didn’t say anything, but it crept into my mind that you might have gotten the gene too. I know it has nothing to do with genes, but I thought ‘There’s Bert; he doesn’t seem to know how to be happy, and maybe he believes he’ll never find out.’”

Bert was silent for a long time, even though they remained facing one another beside the trail. He was looking at her scallop shell, which had flopped over from her backpack and was resting on her shoulder. Finally he spoke. “How would you ever make yourself be happy? I mean who wouldn’t be happy, given the choice?”

“Let’s walk on. Maybe the Camino will help us find our answer.”

__________

Sunday, June 19 4:49 PM

To: [email protected]

Cc: [email protected], [email protected]

From: [email protected]

Subject: Camino Report #7

Dear Friends,

I had never guessed that Spain was such a mountainous country (it looks flat on all my maps), but the past several days have involved much scrambling up and down steep slopes. Coming down from the Cruz de Ferro we had a bad trail, a long steep climb down, and a dazzling blue sky. Yesterday we had the exact reverse. We climbed almost 2,000 feet in less than six miles, mostly in foggy drizzle. We won’t complain about the weather though because when we got to the top of the mountain it turned beautiful again.

Once past the physical hardship, our only concerns have been the really basic need to get where we are going, manage to find some food and lodging, and as often as possible to enjoy the beauty around us.

Last night, we were almost 3,600 feet above the cares of the complicated lands beneath us. With pastures teeming with cattle and sheep, we are literally surrounded by evidence of life’s bounty. Today we came back down those 2,000 feet, but had twelve miles to do it. A piece of cake!

The one thing missing in this tiny town where we are staying tonight is an abundance of computers, and an anxious-looking young woman is waiting for me to get off this one. That’s fine with me, because I have told you all you really need to know about how our trip is going.

One final thing: I have no bars on my Blackberry. If you need to get in touch with me, you’ll have to wait a day or two until we return to the twenty-first century. Oh, and of course I’ll have to remember to turn the contraption on.

Bert (& Helen)

Lately new little aches, pains, and weaknesses had made themselves known. The left knee, which had given out once and threatened to do it again, was perhaps a bit more on the brink than in days past. One toe tended to get numb after a few hours of walking, and he could restore it partly only after vigorous wiggling of all his toes. Also, a pain in his right hip visited him not when walking, but afterwards, when resting. It made sitting uncomfortable, and occasionally almost unbearable. And, of course, the twisted ankle could not be ignored. By this point in their adventure, it seemed clear to him that walking twelve miles in a day was something qualitatively different from walking twelve miles several days in a row. And walking twelve miles a day for several weeks was something else again.

This was a funny day. The surprising wave of additional tiredness at the end fit the rest of it. They started on the steep and challenging trail in weather as gloomy as Helen’s mood. They ended the walk in bright sunshine in this lovely little village on top of the mountain. Looking back at the path from which they’d just emerged, they saw that the patch of woods embracing it was narrow. Just to their left, along the shoulder of the road was a wide stone wall topped with flat field stones. They sat, gazing and enjoying the respite. The views, back down to the valley where they began and across it to cloud-topped mountains, were spectacular.

Bert thought about how the early fog and drizzle, the heavy air, and the grueling initial ascent with no clear vistas to reward them, had led him to pondering his aches and pains.

Ever since La Cruz de Ferro, it weighed heavily on him that maybe Helen couldn’t be a part of the new life he had to make for himself. He had been shaken out of his mood by Helen’s reserved but uncharacteristically candid sharing of her thoughts and talk about cemeteries. What a strange conversation! It was so clear that she had been really upset thinking about her dad and her father, as she called them. He hoped he hadn’t said anything he shouldn’t have. The universe must have created this day for borderline craziness. Somewhere in it was the germ of a hope that Helen might be willing to look to a new future also.

Here on top of the mountain, the air around them felt different. What had changed? Was it the day, the Camino, Helen’s revelations? Had the nature of their friendship shifted? What made their closeness feel more cordial, more relaxed? Could he believe that anything, in fact, had changed?

Whatever the reason, now it was he who was wanting to talk about things he had never revealed before. He didn’t know how it would happen, but he knew when he did, it was Helen he wanted to tell.

They checked into their casa rural, more upscale than their usual albergues. They not only had a private room, but a private bath also. They showered and washed their wet, muddy clothes. The routine of arriving and cleaning up had rejuvenated him. It was still early afternoon. Hungry, they found a rustic restaurant with stone walls, hand-hewed beams, apparent locally made sausages hanging over the bar and, and a roaring wood fire. They grabbed a table next to a window looking out over the distant mountains.

Encouraged by her sharing earlier, over an overpriced bowl of caldo gallego, a rich stew of local vegetables and meat, and a glass of beer, as a tentative first step, Bert ventured a bit of sharing of his own.

“Your bringing up the subject of cemeteries called back to mind an incident from my childhood that also involved one, in a way.”

“It is my turn to be all ears,” Helen said. “I hope I’ll be as good a listener as you were, and that your story won’t be quite as nutty as mine. I wish they’d close the door. It’s drafty in here.”

“No promises, but okay, here it is. When I was about eleven or twelve, my father let me come along one time when his group of amateur archaeologists went on a field trip. He must have been stuck with me for the day for some reason because he had never brought me along before and never did again. The group was exploring a Paleoindian site, and one of the men discovered a human bone sticking out of the ground.”

“Oh my, that sounds both creepy and thrilling.”

“I felt like I was in a movie or something to have that happen when I was there. While all the grownups were talking about it and ignoring me, I took a photo of it—with my Brownie Special.”

“Oh, my gosh. I had one of those too. I thought it was so great that I got a camera of my own, and my sisters were too young. Sorry to interrupt. Go on with the tale!”

“Well, of course, my father and the men left the bones undisturbed and later reported the find to whomever. Ultimately my father told me the bones were turned over to a local Indian tribe.”

“Did you tell your father about the photo?”

“Oddly, I never even considered telling him. I was pretty independent, as you’ve noted before. Your question is pertinent though because the tribe announced that no artifacts could be taken from the site, and no photographs.”

“Artifacts I can understand. But photos?”

“I remember being frightened about having the photo. I didn’t believe in ghosts, but imagined the ghost of that Indian seeping into my room at night. Still, I wasn’t about to give it up. So I compromised with myself. I destroyed the photograph, but kept the negative. At the time it felt like I had a little victory, a little bit of growing up. I’d overcome my fear. It all seemed silly after I became an adult, but I still have the negative. And to this moment I have always kept it a secret.”

“Well, Bert, I love the story. Around the office, you have a reputation for being a by-the-books kind of guy. But I have always felt you followed only the rules that made sense to you. Now I see that you were like that way back when you were just a kid. It makes me feel like I have known you even longer than I have. Maybe if I think about it awhile, I’ll even figure out your conflicted attitude toward the Camino.”

“Perhaps that’s enough about bones for a while though. Let’s go explore the village.”

“I’m ready. The soup and beer will hold me until dinner hour.”

Bert felt good as they got up and paid their bill. Telling Helen his long and closely held secret was a vaguely emotional and surprisingly pleasant experience. He found himself thinking he might try it again sometime. She hadn’t reacted negatively, and even seemed to have enjoyed it. He had a bigger secret that weighed on him, and sometime she might learn about that one too.

________________

An opportunity came that very evening. They were drinking wine in the restaurant at their casa rural, finishing off the bottle that had come with their dinner. They were both relaxed and mellow. It seemed like he probably ought to grab the momentum.

He hadn’t gotten over his reticence to talk to her about things he thought of as private, and talking about the photo had been difficult for him. But it hadn’t turned out badly. He wasn’t as embarrassed as he expected; he didn’t feel stupid. He was relieved that she had taken him seriously. Her insights about his relationship with the rules and expectations were a total surprise—probably right on the mark, he thought.

She had opened the gates by sharing her concerns earlier. He thought of her as much less willing to share than he—and he was Fort Knox.

But, then he had second thoughts. This was probably not the right time to talk about the second secret. It would be too much pushing their envelope all in one day. They had plenty of days left on the Camino. If it seemed like a good idea later on, he would reconsider.

His big secret wasn’t damning, at least not in the usual literal sense. And it wasn’t the kind of thing most people would keep wholly to themselves. Nevertheless, it was a heavy burden on him. Why, he wondered, had it been like that it all these years? Like keeping that old negative, he wished he’d known the Cruz de Ferro tradition earlier. He would have tied them both to a stone and kissed them goodbye.

Since the Cruz de Ferro he had spent a lot of time, in what he had come to think of as his walking mind, with thoughts that seldom rose to his consciousness and even less frequently were allowed to stay there. The core of an answer to the question he usually ignored so assertively had begun to come to him. But he wasn’t there yet.

He now suspected that Helen may have had similar experiences of self-recognition. If he shared his secret with her, she might have an insight like she did about his relationship with rules. She might be able to help him to fill in the parts he was still missing. He liked her comment about feeling like she’d known him since he was a boy. But what if, this time, her comment wasn’t comforting?

Of course, that was the real problem; and that was why he was hesitating. Where would it end? It was why he wasn’t too upset when she pulled away that weekend after their divorces. In truth, he hadn’t been any more ready than she to try again. Once you start sharing, each secret might be more painful than the last. He wasn’t quite ready to begin filling in all the missing parts of himself.

On the other hand, maybe that’s what the Camino and that Cruz de Ferro message are all about. Bert ordered a second bottle of wine for them. The genie was getting out of the bottle. He decided this would be as good a time as any. He steeled himself.

“There’s something about me that you don’t know,” he said. “It’s another long-kept secret, and it’s been bothering me for the past few days, like the concerns you shared with me earlier. Your reaction to my photo story has nudged me to share this one as well.”

“Okay,” she said. “I might be more worried about what you are going to say except that I found the photo story to be so interesting. And I liked what it told me about you.”

“Actually, this has been bothering me for years, so why should I be talking about it now? I suppose it’s the Camino. Walking has gotten me thinking about it and wanting to tell you. Anyway, I don’t feel like we can be real friends unless you know. So here goes.”

“Hello.” Through the room came Jacques and Hélène, a couple they had spoken with while having a café con leche at a bar along the trail a few days ago.

“Hold that thought,” whispered Helen.

“Damnation,” responded Bert.

Burley, gray-bearded Jacques, still in shorts despite the mountain cold, and pale, slight Hélène with her plastic-framed glasses—Helen’s almost namesake—came over to the table and joined Bert and Helen. Bert hid his frustration well, but Helen gave him a knowing smile. The four of them compared notes about the relative values of their respective dinners. The Canadians had dined across the street at another restaurant and were just returning to the casa rural.

“Where are you staying tomorrow? Maybe we could meet and see the sights together.”

They quickly ascertained that they were planning to walk to different destinations—the Canadians were stronger walkers—and after expressions of regret, they bid their farewells.

Helen’s interested eyes gave Bert the clear go ahead to resume his monologue at the point where they had been interrupted.

“As I was about to say, you had every reason to think that I had a more or less normal background. Coming up, that is, just a normal American childhood, nothing special. In fact, one thing was different. You see, I graduated from college at age nineteen, and got a PhD at age twenty-three, even though I tried to slow things down as best I could. So, there you have it.”

He waited for what seemed a very long time, expecting a gasp. Or what? He didn’t know what to expect.

“Bert! That’s no deep, dark secret. Why, I thought you were going to tell me you were a convicted criminal or had a rare genetic disorder that would rapidly bring on psychosis as you approach your sixties. Why would the fact that you’re a quick study be something to keep hidden?”

“You don’t understand. When this is happening I’m in my early twenties, I am—as you say—a quick study, and everyone around me thinks I’m a prodigy. It wasn’t so much my parents—they wanted me to go into business management. It was others, especially teachers, and along with them, it was me too. I came to believe that I had truly extraordinary talents. It was my destiny to become a great scientist.”

“And you never did.”

“No, barely twenty-three years old, I was too young to be a professor. Some of my fellow graduates, who were mostly about a decade older than me, went on to postdoctoral programs in order to sharpen their skills and better qualify for academic positions. I didn’t want to do that. I thought I was tired and needed a break. Actually there was something else. It was hubris I guess. I didn’t think I needed a postdoc. I was ready to launch into the real world, and no additional tune-up was required. I thanked my professors for suggesting a postdoc, but I didn’t believe my scientific credentials needed to be enhanced.”

“How did you wind up in the Fish and Wildlife Service?”

“Well, Fish and Wildlife was willing to hire me, even at my tender age, and I felt the organization was doing good work, had a great need for good science, and could benefit from my super sharp scientific skills. Plus, it was a way to get a taste of the real world before I returned to academia.

“As things turned out, and as you know, the Service did have a great need for good science, but I eventually learned it wasn’t the kind I had earlier excelled at. Fish and Wildlife Service science was no better or no worse than academic science, but it wasn’t the arena where a prodigy could make much of a difference.

“I stayed on, and after a few years my academic credentials had dimmed. I sensed it was already too late to go back to academe. I felt I was doing important work with Fish and Wildlife, but I was no longer riding the crest of the wave. By the advanced age of thirty, still younger than most of the folks who got their PhDs with me, it was clear that I had failed to achieve my destiny. There was nothing else. No mountains to climb. No chance for greatness.”

“So you were doing important work, but not working at the level of excellence you expected of yourself. Is that what you’re saying?”

“At first I didn’t want to reveal my years as a prodigy because I didn’t want my colleagues to view me as something different. I didn’t even tell people I had a doctorate. I didn’t want to be an odd duck. As time went on, my reluctance to tell people became no longer the desire to appear normal to my co-workers. Instead, it was the failure and waste of it all and the accompanying embarrassment that bothered me. That—my failure—was what I was reluctant to reveal to others. At some level I have long realized that my failure is a heavy burden on me, but it wasn’t until walking on the Camino that I began to fully get my secret out into the conscious regions of my mind. My burden is that I had a great opportunity, and I let it go down the drain.”

Helen seemed anxious to set the conversation on a better course. “Bert, I’m glad you told me. Odd, isn’t it, how things we have kept completely to ourselves are so painful to share. First of all, it’s horrible carrying around such a burden for so long. Then telling someone else about it, just saying it out loud, brings back the agony that made you keep it a secret.

“I think I can see how you must feel about failing to stay on the crest of your early accomplishments, but I have to tell you I don’t believe in destinies. At some point as a teenager, I thought I would become the nucleus of a family with a loving husband and four wonderful children. Of course it didn’t happen, it can’t happen, and despite what I thought as an eighteen-year-old, it never was my destiny. In fact, right now my destiny is Santiago. Actually I believe my destiny is unknown, but nevertheless is something I can partially control, or at least influence.”

She appeared to be gathering her thoughts. She stared into a little lantern on the table, seeming to seek light from its flickering candle. The room was dark, and the candle’s reflection in her eyes gave them an emerald cast that he’d never noticed before.

“Bert, you were little more than a teenager. You had gotten positive feedback from everyone around you, and had come to believe all the nice things people said about you. Who wouldn’t? And now you’re second-guessing a decision you made thirty years ago. You’re being much too hard on yourself. And don’t you think if becoming a great scientist really was your destiny, it would have happened somehow? Could something as trivial as taking a job after graduate school have derailed a destiny engraved in the annals of the universe? Maybe I’m repeating myself, but you are a good friend and I hate to see you walk around in a prison you’ve built for yourself.”

Was she scolding him? Of course not. Why wasn’t he feeling much of anything? Her way of seeing his decision to join Fish and Wildlife and his sense of having failed to achieve what he was supposed to, given his talents, was a new way of thinking about that time in his life. Maybe she had it right, but the conclusion was too different for him to go there yet. He needed to think about it more. He would do that, but not just yet.

Something had stuck in his mind, however, and he couldn’t let it go.

“I know this discussion has been about me,” he said, “but what you said about your destiny . . . what you once thought was your destiny that never materialized . . . is too important to let just float by. You have told me more than once that you have no regrets about your decision to get a divorce. I think I still believe you, but what you just said was different—the part about a loving husband and four children. I suspect you may have regretted missing that part of your life from time to time.”

“You may be right. Yeah, there could be something there. By the way, the wine is gone.”

“Yes, and I’m really tired. It’s been a long day.”

“Me too.”

“Let’s see what tomorrow brings.”

He didn’t know what to think. He didn’t feel like he was saving his life, but could it be that he might help Helen to save hers?

____________

The next morning as they had loaded up their gear and headed down the stone pavement, Bert was still ready to talk.

“Our conversation from last night got me thinking—thinking so much that I didn’t do too much sleeping. But that’s okay. I don’t mind the lack of sleep.”

“I hope nothing I said made you toss and turn all night. Good thing we weren’t in a crowded albergue.”

“Oh, no. I don’t even know which one of us said it. Maybe both of us did. But the word failure came up, and we both recognized that I had been carrying around a sense of failure because I hadn’t lived up to expectations, and it wasn’t anybody else’s, but just my own expectations of myself.”

“I don’t remember either who said it first.”

“Our little talk got me thinking about my other failures, and made me realize I need to come to grips with them too. There’s the matter of my failed marriage. You have nothing to do with that, and I’ll tackle dealing with that one on my own. The question is whether I will let that failure—and make no mistake, there was failure on my side as well as hers—will I let it take charge of my future life and determine what I will and will not try to do? So, even though I won’t drag you into that one, there is one where you can probably help because you’re knowledgeable and have some relevant experience. That one has to do with my career.”

“We’ve been giving each other career counseling for years in our informal, gossipy sort of way,” said Helen.

“I don’t expect any answers or solutions from you, but I do want to share my feelings with you, just so you know where things lie. And maybe someday, a situation will come up in which you have a key bit of advice to offer.”

He retraced the times in their careers when they had worked together in reasonable contentment. Then she had made the critical move that put her career on an upward and rewarding track while he remained behind and suffered a series of disappointments. His recommendations on protections needed for several endangered species had been cast aside in the face of what he regarded as political expediency.

On a seeming tailspin, his career appeared bound for a crash. But it had been rescued by a temporary promotion to a position where he performed competently. The promotion became permanent, and he expected to continue in it or a similar post until retirement. It didn’t really make him happy, but it was better than before.

His health intervened, however, and then came the task force. This was as close to being happy at work as he’d been since she’d left for the Florida job.

Helen knew all of this, but she let him go on so she could get some sense of how it affected him. Could he ever be happy with his work? She cut him off.

“Bert, I know what you are going to say, and you needn’t tell me, because I’m way ahead of you. I really am. I’m way ahead of you.”

He looked shocked by the interruption, but waited for her to say what she wanted to.

“You have the answer, Bert. You have it yourself, and you just don’t know how to use it!”

She stopped and pulled him to the side of the trail, where they could talk face to face. Her words were soft and measured. “Remember our discussion back in Estella, I think it was Estella, where you had talked to that man and had gotten curious about people’s motivations. It was about poorness in spirit, and your cousin, and how maybe she thought happiness would forever be beyond her reach. You joked about a poorness-in-spirit gene. I didn’t say anything, but it crept into my mind that you might have gotten the gene too. I know it has nothing to do with genes, but I thought ‘There’s Bert; he doesn’t seem to know how to be happy, and maybe he believes he’ll never find out.’”

Bert was silent for a long time, even though they remained facing one another beside the trail. He was looking at her scallop shell, which had flopped over from her backpack and was resting on her shoulder. Finally he spoke. “How would you ever make yourself be happy? I mean who wouldn’t be happy, given the choice?”

“Let’s walk on. Maybe the Camino will help us find our answer.”

__________

Sunday, June 19 4:49 PM

To: [email protected]

Cc: [email protected], [email protected]

From: [email protected]

Subject: Camino Report #7

Dear Friends,

I had never guessed that Spain was such a mountainous country (it looks flat on all my maps), but the past several days have involved much scrambling up and down steep slopes. Coming down from the Cruz de Ferro we had a bad trail, a long steep climb down, and a dazzling blue sky. Yesterday we had the exact reverse. We climbed almost 2,000 feet in less than six miles, mostly in foggy drizzle. We won’t complain about the weather though because when we got to the top of the mountain it turned beautiful again.

Once past the physical hardship, our only concerns have been the really basic need to get where we are going, manage to find some food and lodging, and as often as possible to enjoy the beauty around us.

Last night, we were almost 3,600 feet above the cares of the complicated lands beneath us. With pastures teeming with cattle and sheep, we are literally surrounded by evidence of life’s bounty. Today we came back down those 2,000 feet, but had twelve miles to do it. A piece of cake!

The one thing missing in this tiny town where we are staying tonight is an abundance of computers, and an anxious-looking young woman is waiting for me to get off this one. That’s fine with me, because I have told you all you really need to know about how our trip is going.

One final thing: I have no bars on my Blackberry. If you need to get in touch with me, you’ll have to wait a day or two until we return to the twenty-first century. Oh, and of course I’ll have to remember to turn the contraption on.

Bert (& Helen)

Kindred Spirits

Triacestela to Samos

Monday, June 20

Santiago grew closer, and Helen and Bert were experiencing the first real rain in days. Despite the need to wear ponchos, Helen felt upbeat. Today’s rain was not like the hours of drizzly gloom enveloping them on the climb to O’Cebreiro. This warm, gentle rain felt friendly and nurturing. Now in Galicia, with its Ireland-like climate and look of the land, rain was more expected.

This wet weather was inconvenient, but hardly threatened the disaster that the soaking rain had seemed as they walked their first few days through the Pyrenees. Today, rainy weather felt to her like just an inseparable and essential part of their Camino. She smiled as she remembered fleetingly having had a similar thought way back on Day Two in Zubiri.

They were occasionally sharing the muddy road with farm animals. Bert took the lead when that happened. Helen was hesitant to compete for a travel lane with oncoming cows. He seemed confident, but Helen wasn’t certain that cows would seek to avoid head-on collisions with humans. She noted the lack of concern on the part of the farmers driving the cattle along, and this gave her added confidence that Bert wouldn’t be mowed down.

Bert mentioned that all the many cattle they had seen in Spain so far were the same color, and he thought they might be Brown Swiss. The words were scarcely out of his mouth when they rounded a bend and came upon a pasture with black and white heifers. From that point on they passed other herds, some partially and some entirely populated by black and white cattle.

Bert said something about the dogs and their apparent lack of motivation, and she agreed. The cattle seemed to be following the people, and the dogs following everybody else. What was the relationship here?

With no cows in sight for the moment, she was walking a few steps ahead of Bert. She was surprised and delighted when through the mist she spotted a familiar person sitting on a low stone wall. Ilsa was trying improbably to write in her notebook held beneath her poncho, peering down through the neck opening to see the page. She looked up, her expression registering recognition when her eyes went from Helen to Bert. Her rain-streaked face broke into a broad smile.

“Well, look who’s here,” she exclaimed, with evident delight.

Helen rushed up to her. Somehow in the time it took Helen to cover a few meters, the notebook and pencil were stowed and it was poncho to poncho hugs all around.

Having long since lost track of the days, Helen couldn’t remember how long it had been since they last saw Ilsa, but guessed it must have been the better part of a month.

“How have you been? And how have we missed seeing you along the trail?” Helen thought they must have been walking close to Ilsa, and wondered why their paths had never managed to cross.

“Oh, I took a couple of days off in Sahagún. Then a couple of days later I twisted my knee, and had to lay low for another day until I was confident it was going to take care of itself. I got way behind my schedule, until I hopped a bus from Molinaseca to O’Cebreiro. So I suppose I’ve mostly been a day or two behind you. But that’s all history, and now the three of us are here together.”

“Shall we walk together for a while?”

“Oh, yes, and maybe we’ll find a café before long. I could stand to spend a few minutes without this poncho clinging around me.”

“You can count me in,” said Bert, who other than a brief perfunctory hug, hadn’t so far been brought into the conversation.

They continued down the trail, with Helen and Ilsa walking side by side like teenage friends, and Bert following close behind them.

Helen briefly wondered why she liked Ilsa so much. Maybe it was the way Ilsa reached out to them with her story, without any expectation that they would reciprocate by opening up to her.

“How has your Camino been going? Has it helped to improve your spirits?” Reluctant to pull Ilsa back to the painful revelations about her role in her daughters’ estrangement, Helen’s inquiry was as generic as she could make it.