|

You can read this section of the book here on screen, or use the buttons to download it as a PDF or Word file to read on another devise. |

|

Second Wind on the Way of St. James

© 2013 by Russell J Hall and Peg Rooney Hall Published by: Lighthall Books P.O. Box 357305 Gainesville, Florida 32635-7305 http://www.lighthallbooks.com Orders: [email protected] No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, either electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, except as specified by the authors. Electronic versions made available free of charge are intended for personal use, and may not be offered for sale in any form except by the authors. Excluded from copyright are the maps, which are based on the work of Manfred Zentgraf of Volkach, Germany. Like the original, our adaptations of his map remain in the public domain. Second Wind is a work of fiction. Many experiences of the authors on the Camino have inspired and informed themes of the book, but people and events depicted are products of the authors’ imaginations; any resemblance to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental. |

Episode 4

Stage Four:

Faintly Glimpsed Mirrors

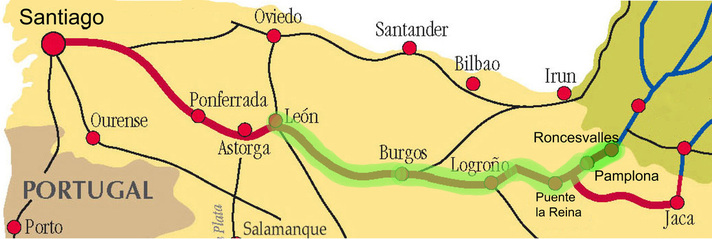

Burgos to Leon

The Brothers

Burgos to Hornillos

Monday, May 30

In contrast to the miles of neighborhoods on the east side, walking out of Burgos to the west was a piece of cake—a pleasant surprise. Many of the dwellings were single-family homes or expensive-looking garden-style apartment buildings. Abundant red, pink, and orange roses graced most yards. The Camino left the city streets and trailed through a park. The trail was wide, flat, clay, and reserved for pedestrians, bicycles, and baby strollers. Helen and Bert cleared the city and were in the countryside before Bert expected it. Mounds of white rocks lined the trail occasionally, as if dumped by a glacier or by a god, he thought. Brilliant red poppies scattered themselves in the rocks, inviting many tries for the perfect photograph.

Six and a half hours after leaving the outskirts of Burgos, they walked into the town of Hornillos. All the accommodations there were filled to capacity. Bert surprised himself by not feeling immediately panicked, even though arriving to a completo sign had been one of his biggest fears.

Helen’s guidebook suggested there might be a shortage of accommodations. It recommended another inn in a nearby town, providing a phone number and the information that the proprietors of the Casa Rural El Molino would pick up hikers and return them to the Camino in Hornillos the following morning.

Helen had committed to memory a few Spanish words and phrases useful for arranging accommodations, so Bert gave her his Blackberry and read off the number from the guidebook while she keyed it in. Having had good coverage most places along the trail, here the Blackberry appeared to have a weak signal. Even when it seemed she might have been able to make a connection with the inn, the phone rang and rang with no one answering.

They were sitting on the stone steps of the church above the small town square, which was crowded with people apparently staying in the filled albergues. The sun was blazing down on them. The weather had been good. Now they were hot, tired, discouraged, but not yet in a dither. There was nothing to do except sit next to their packs and keep trying to reach the casa rural. They had no Plan B, and Bert couldn’t imagine how they might come up with one. This was one of those situations where the conventional advice was “just call a taxi.” He wondered how they would go about getting one, especially given the problem they were having with the phone. And where would they tell the cab driver to take them? Finally on the fourth or fifth attempt someone did answer, but with the weak signal and Helen’s inability to follow the rapid-fire Spanish of the woman on the other end, no arrangement could be made before the call was dropped.

Helen’s shoulders were tense. She got up, paced into the square and looked around. She paced back. Bert thought she was getting desperate. He couldn’t imagine any way to help and knew that saying something like “things will work out somehow” would be worthy only of a nighttime TV comedy routine. He doubted she’d laugh.

She headed down a narrow side street off the square, saying she was going in search of a better signal. Bert stayed behind on the steps to look after their gear. He wished he knew how she was managing. He thought that Hornillos was small, but did it have a maze of streets where one could get lost?

When she finally returned he learned that it had been her good fortune to find a kind Spanish man who offered to help her with the call. Somehow through the teamwork of Helen and her helper, the call was made, the message was delivered, and the information conveyed that someone from the casa rural would be picking them up in thirty minutes.

“Wow, it’s lucky you met that man; we have perhaps encountered our first Camino angel,” Bert said. “After hearing so much about how the Camino will provide an angel when you need one, I was beginning to wonder if we were scaring angels away. But he appeared, right when we were getting desperate.”

Helen laughed, greatly relieved things seemed to have gotten sorted out.

“Now that our lodgings are settled, I am reminded that in addition to being tired and hot, I’m hungry too,” she said.

They had found no place along the way to get lunch, and dinner was nowhere in sight. Bert decided to go back to a tienda—they had passed it just as they got to town—to get them some basic supplies to assuage their crying bellies. He liked their ‘tienda picnics’ with cheese, bread, chorizo, wine, and when they could get them, little plastic packages of green olives too. The packages read aceitunas con huesos or aceitunas sin huesos—literally olives with or without bones. While some American olives have pits, it appeared that in Spain they have bones.

Bert congratulated himself for having thought to bring along a fishing knife superbly adapted to preparing little feasts, with a minimum of cleanup required. Of course they never would have left home without a corkscrew.

He easily found everything he wanted in the tiny store, with one exception. He noted that the only loaf of bread visible was far too big. Not only was it too much for them to eat in a day or two, but it was too long to fit in his pack. Thinking the store might have some supply of bread out of sight, he asked the woman behind the counter if she had a small loaf of bread--tiene una pequeña pan? She shook her head, and Bert worried that she had not understood him. But unruffled, and undaunted by Bert’s poor Spanish, she took down the loaf, ripped off one end, and handed it to Bert. Apparently he was the one who didn’t understand. He paid and hurried out, not wanting to miss the promised ride to the other town and its inn.

When he got back to the square, the vehicle from the casa rural had not yet arrived. Helen was chatting with some other people and told him a French couple they had met before were also waiting for a lift to El Molino. They leaned their packs against the front of an albergue and waited next to them in the thin band of shade cast by the building. Too weary, they made no attempt to strike up further conversations with the other hikers crowding the little square. The time for socializing might come later, when and if they had rested a while.

From the number of people lounging in the hot square, Bert concluded that the local albergues were not only full, but were probably lacking in indoor seating. Why else would so many people be spending the afternoon draped on steps in the sun-drenched village square? They had passed other albergues where people were hanging around, often in uninviting, starkly basic courtyards. Other times when it was raining they had passed albergues where, peering inside, they saw people sitting on bunks in dark, dank-looking rooms. The image of what might lie ahead was troubling, but there seemed to be no other choices.

He was only too aware that they were at the mercy of the Camino when it came to getting someplace to stay for the night. Earlier a pilgrim had told them that giving yourself up to the Camino and learning to joyfully take what it offers you is one of its greatest gifts. Waiting for a ride that might or might not show up didn’t seem like a gift just then. On the other hand, what Bert had seen in Hornillos was unappealing, and he was not altogether unhappy that the town was unable to accommodate them. He hoped they would do better by getting a second chance.

In the promised thirty-minute waiting period a few vehicles—one car, two small delivery trucks, and a farm tractor to be exact—entered the square, and kept going. Perhaps forty-five minutes had elapsed when a car stopped in the small square. Getting out, the young man said, “El Molino?”

Bert, Helen, the French couple, and two other people stepped forward. This was clearly a problem; there were too many of them. The small car could only barely accommodate four extra people with their packs and other gear, and fitting in six was beyond imagination. The man said something in Spanish about expecting to pick up four people. He was obviously agitated, trying hard not to make eye contact with any of them, probably fearing that might indicate they should climb in.

Getting out his cell phone to call the inn, he apparently experienced the same problems Helen had encountered with the Blackberry—first no answer, and then twice his calls were dropped before he had gotten the needed information. The French couple, clearly impatient, put their backpacks in the open trunk, apparently expecting this to make a difference in their priority for transport.

Bert and Helen held back, however. It seemed clear that the man was not going to act without further instructions. Finally he got through and learned the names of the people he was to pick up. He asked Bert and Helen and the French couple—the man and woman—to get in the car. The others—two French women—were out of luck, but apparently in the queue and would be picked up later.

The trip to the Casa Rural El Molino convinced Bert that the guidebook had been guilty of a double exaggeration in reporting that it was in a nearby village. He guessed they must have traveled at least twenty miles over a patchwork of rural roads to reach their destination. Moreover, the place was far out in the countryside, with no village anywhere nearby. Even if they had gotten directions and could have found their way, it would have taken them a very long day to walk from Hornillos to El Molino.

Once out of the car, they discovered that the place was crowded. Following some initial confusion about what to do with them, a young woman who Bert never saw again led the two couples to their rooms. It soon became clear why they had had such difficulty in getting through and then getting there. El Molino was hosting a huge family reunion with at least fifty attendees, and the staff was obviously overwhelmed. The driver who had picked them up, they learned, was a volunteer pressed into service when no one else was available. So they had a reasonable explanation for the difficulties they had encountered, and these were soon forgotten when they took measure of the inn.

Living up to its name, it was obviously an old mill, with a stream and a millrace running under the building. Ducks and geese stood on the banks. Bert imagined that the grounds must have been beautiful at a different time of the year, but right now they were covered by great accumulation of the cottony seeds from the nearby grove of poplar trees. The messy debris looked like snow. It was on the patio, the tables, the chairs, the lawns, and driveways. The waterways were clogged with several inches of soapy-looking foam.

The inside of the old mill had been extensively remodeled. Their room had all modern conveniences and was uncommonly large for a European lodging. They had a pleasant sitting room shared with several other rooms and access to a keg dispensing free beer. This they guessed was at the beneficence of the family reunion, rather than the inn. Spanish and French were mostly spoken, but they did get to listen to some painful English.

They were sitting in the large common room with the impatient souls who had thrown their packs into the open trunk in Hornillos. The man was on his cell phone trying to make room reservations for the next day. He obviously spoke no Spanish and apparently the innkeeper on the line spoke no French. English was the possible second choice for each. The Frenchman’s was the most atrocious English Bert had ever heard. Somehow he seemed to have gotten the notion that it was appropriate to insert a “hello” after every second or third word. Bert thought the man might have confused the word “hello” with “okay.”

“Hello, hello. Je veux . . . une chamber, hello. Avec toilet, hello. Tomorrow, deux persons, hello? Je ne comprends pas, hello! Pour two . . . two personnes . . . Hello!!”

It was ludicrous, amusing, and horrifying. Bert looked at Helen. She looked away so she wouldn’t start to laugh out loud.

Toward evening the wind picked up and a thunderstorm appeared to be rolling in. The dozens of participants in the family reunion had been seated at outdoor tables and chairs in the grove of poplars not far from the building. Some left well before the storm hit, while others waited until the last minute. When the rain did begin to come down hard, the few holdouts fled. The family reunion was over, and the inn began to return to normal.

Dinner wasn’t until nine o’clock, so they read for a while, trying to pick up the plots of the paperbacks that had languished in their backpacks for days.

When the dinner hour finally arrived, with other guests they filed into a large dining room with a long table. It ultimately seated the two of them and thirteen other guests. The French couple and the two French women who had to wait in Hornillos for the second shuttle sat at one end. Helen was able to speak with them with her passable French, but was unable to keep up with their conversation. She knew better than to try to talk to the man in English!

At the other end of the table were five Germans, including a man they had chatted with earlier. He spoke English, but it was clear that he enjoyed talking with the other German speakers more than working to converse with the two of them. They were near the middle of the table, as were two Spanish couples. It appeared to Bert that this evening they would need to rely on each other for conversation.

He soon discovered otherwise. The man who sat across from Bert and Helen introduced himself as Oscar. His English did not come easily to him, and his three companions apparently did not speak it at all. Obviously friendly, outgoing, and energetic, Oscar was not to be deterred from making new friends by something as trivial as a language barrier. Using his limited English and patient Spanish that Bert found relatively easy to follow, he told them his story.

The other Spanish man, who sat next to Bert, was his brother Ernesto, he said. They were from Sevilla. They were walking the Camino from Burgos to Santiago together with their wives, who had never met before two days ago, when their adventure had begun. The brothers looked very much alike. They had close-cropped hair, round faces, and bushy black eyebrows. But what made them so resemble each other was their round, sparkling, brown eyes. Flashing eyes seemed to Bert a funny feature to note in two grown men, but there they were, undeniably calling attention to themselves.

Ernesto may have gotten a wordless cue from his brother, or perhaps understood more English than he let on, because he turned, gave a big smile, and shook hands with Bert, finishing with a pantomime introduction of his wife. Oscar belatedly introduced his wife also. She reached out to shake hands and seemed as eager to be friendly as her husband, but she gave no indication of understanding the first word of English. She remained on the fringes of the conversation. Oscar patiently kept her informed of the drift of the conversation.

As they chatted, the first offerings of what was to be a multicourse meal were served, beginning with bread and olive oil. Immediately Bert understood that this was not to be the typical dinner. Instead, it was a real Spanish meal—the kind of meal the locals enjoyed while eating and talking long into the evening. An early course included fried strips of pork that the Spanish called pancetta. He recognized it as only a distant relative of the famous Italian bacon of the same name. Instead it was “side pork,” “sow belly,” or “white bacon,” a staple of country cooking in America, long in disfavor because of its artery-clogging qualities.

Ernesto was gray-headed and looked older than Oscar, and Helen asked whether he was Oscar’s big brother.

“Once años,” said Oscar.

“Eleven years,” said Helen.

Oscar nodded. In a remarkable combination of languages and gestures, he made known that he and his brother had not seen each other for almost twenty years. He had been a teenager when his brother joined the army, and after the army Ernesto had gone to live in Venezuela. He had returned to live in Spain recently, and through relatives the brothers had gotten in touch. Realizing that they had been separated for almost their entire lifetimes, they felt they had much to catch up on. They decided to walk the Camino together to get reacquainted. So far they had already discovered they had much in common and were obviously enjoying each other’s company.

Their wives weren’t sure that the Camino was for them. Indeed, the brothers were walking and planning to continue all the way to Santiago, but the wives were traveling by car. It wasn’t clear to Bert whether they would be following their husbands along the way and joining them from time to time or whether they were just dropping them off. He did pick up that the intention was that the wives would be getting to know one another also.

Perhaps they are, thought Bert, but it is clear that they are not enjoying the experience nearly as much as were their husbands.

Oscar pointed out a framed poster on the wall behind Bert and Helen that they hadn’t noticed. It was an advertisement for an American movie about the Camino called The Way. They had heard of it and had even seen a trailer. They didn’t know until Oscar told them, however, that the cast and crew had stayed in this very inn during filming. Bert resolved to see the film when it was released in the United States, hoping to catch scenes of El Molino and possibly other familiar sights from the Camino.

Oscar wasn’t finished. They had remarked about the food, and he had some dining suggestions for them. Most of his suggestions seemed to be local specialties, and neither Bert nor Helen could understand what he meant. He asked whether they had paper with them, and Helen took out a small notebook she carried. He got his wife to produce a pen, and he wrote down some things they should ask for when the opportunity arose. When Bert asked for the meaning of one word, he drew a little picture of a goat, and said joven, indicating that the meat in the dish was from a young goat.

The food and wine kept coming, then cheeses, and then a sampler of aperitifs. Just after eleven the meal was declared to be finished, and everyone got up to leave.

Thinking about the chaotic arrangements that had gotten them to El Molino, Bert was a bit concerned about the following morning and how they would get back on the Camino. Helen had overheard a discussion between one of the French women and the owner’s wife concerning arrangements for the morning. She said that from what she could make of the exchange, it appeared that the French couple wanted to be delivered to Hornillos at seven, and the other woman was offering them transport at nine. Helen hadn’t heard the resolution of this apparent conflict, but she told Bert she doubted that the French woman would be leaving at seven. Bert would also have preferred seven, but decided that eight would be fine. If they didn’t leave until after nine, however, they might have trouble making it to Castrojeriz in good time. They discussed it and decided they would be ready to depart at eight, but at the same time be ready to go with the flow. They surely wouldn’t be walking back to Hornillos.

As things developed the next morning, they had finished breakfast, paid their remarkably inexpensive bill, and were ready to leave for Hornillos at ten before eight. They waited only a few minutes before the owner showed up in an ancient and obviously much used Range Rover and sped them off to Hornillos.

Despite the lateness of the night before, Bert felt refreshed. They were ready to begin walking as soon as they were discharged into the same square where they had been picked up a scant seventeen hours before.

Bert began the conversation once they were out on the open road.

“Meeting Oscar and Ernesto for some reason reminded me of my own family. It struck me that I know my brother and sister about as well as the Spanish brothers knew each other. I haven’t exactly lost track of them. I think I could get in touch with them if necessary. But I haven’t seen either of them in years. I can’t imagine we would have much in common. On the other hand, who’s to say? Oscar and Ernesto seem to be getting along all right, despite the significant age difference. I know a reunion of that kind with my siblings will never happen, but the brothers did make me think about them.”

“Maureen, Donna, and I were quite close when we were growing up, even though I am a couple of years older and only a half-sister. We’re in touch mainly by e-mail. I think we have a good relationship, but we aren’t all that close any more. Their lives have been different from mine. They’ve had long marriages and children. Both of them went to work when their kids started school. They have good jobs, but you wouldn’t really say they have careers like ours. I like both of them, but we haven’t had many shared experiences since our childhood days. I was a little surprised that they seemed to be interested in our Camino.”

“Do you see them often?” Bert said, finding many things having to do with family dynamics unfamiliar, and therefore mildly interesting.

“I see each of them maybe once a year, on average. Weddings, funerals, graduations usually provide the reason. Lacking one of those events, I try to make an effort to visit. It’s been a bit harder since I’ve been at the refuge than when I had an eight to five job. I’m both tied down and far from the main travel hubs. You’ve touched a tender spot here. I wish I could be a better sister to them. I may be wrong, but I think if I tried harder I might still be helpful to them, like when I was their big sister.”

“Well, maybe you can feel better now that you’ve discovered someone who is far worse at holding up his end of sister- and brotherhood than you are,” said Bert, hoping to end the discussion on a lighthearted note.

Helen seemed to want to move on to another topic also.

“I’m glad that all the albergues, hostals, hotels, and the like in Hornillos were completo,” she said. “El Molino was a real experience.”

“I agree. We saw the old mill, had a real Spanish meal, met the brothers, slept in nice beds, and we got to speed at a hundred kilometers an hour over crumbling Spanish country roads in a rickety Range Rover. We enjoyed the first several of our experiences and survived the last.”

“I really liked Oscar. Both brothers. I liked them both. They seemed so happy to have rediscovered each other. Maybe I should get my sisters to come on the Camino with me sometime. Silly thought! They’re much too busy, I doubt they enjoy walking, and what would we talk about?”

Bert looked over at her, curious about her unusual mention of her sisters. But she was looking off to the side and he didn’t catch her eye.

“Back to my first thought,” she said. “After meeting Oscar, I don’t think I’ll ever again be reluctant to talk with somebody just because I’m not good at their language. If there had been other English speakers, we would have had to talk with them, and that probably wouldn’t have been any fun at all.” “Yeah, it was a good time,” said Bert. La Noche Blanca and then El Molino—both had been special, almost magical experiences. Maybe the Camino was being kind to them, and maybe more good things awaited them.

“And the idea,” said Helen, interrupting his thoughts. “Imagine the idea of using a walk on the Camino as a way of reconnecting with somebody you haven’t seen in a long time. I wonder . . . how could anybody ever come up with a preposterous idea like that?”

This time she looked toward him just as he was looking to her.

“I wonder,” said Bert, noting the teasing in her eye.

Six and a half hours after leaving the outskirts of Burgos, they walked into the town of Hornillos. All the accommodations there were filled to capacity. Bert surprised himself by not feeling immediately panicked, even though arriving to a completo sign had been one of his biggest fears.

Helen’s guidebook suggested there might be a shortage of accommodations. It recommended another inn in a nearby town, providing a phone number and the information that the proprietors of the Casa Rural El Molino would pick up hikers and return them to the Camino in Hornillos the following morning.

Helen had committed to memory a few Spanish words and phrases useful for arranging accommodations, so Bert gave her his Blackberry and read off the number from the guidebook while she keyed it in. Having had good coverage most places along the trail, here the Blackberry appeared to have a weak signal. Even when it seemed she might have been able to make a connection with the inn, the phone rang and rang with no one answering.

They were sitting on the stone steps of the church above the small town square, which was crowded with people apparently staying in the filled albergues. The sun was blazing down on them. The weather had been good. Now they were hot, tired, discouraged, but not yet in a dither. There was nothing to do except sit next to their packs and keep trying to reach the casa rural. They had no Plan B, and Bert couldn’t imagine how they might come up with one. This was one of those situations where the conventional advice was “just call a taxi.” He wondered how they would go about getting one, especially given the problem they were having with the phone. And where would they tell the cab driver to take them? Finally on the fourth or fifth attempt someone did answer, but with the weak signal and Helen’s inability to follow the rapid-fire Spanish of the woman on the other end, no arrangement could be made before the call was dropped.

Helen’s shoulders were tense. She got up, paced into the square and looked around. She paced back. Bert thought she was getting desperate. He couldn’t imagine any way to help and knew that saying something like “things will work out somehow” would be worthy only of a nighttime TV comedy routine. He doubted she’d laugh.

She headed down a narrow side street off the square, saying she was going in search of a better signal. Bert stayed behind on the steps to look after their gear. He wished he knew how she was managing. He thought that Hornillos was small, but did it have a maze of streets where one could get lost?

When she finally returned he learned that it had been her good fortune to find a kind Spanish man who offered to help her with the call. Somehow through the teamwork of Helen and her helper, the call was made, the message was delivered, and the information conveyed that someone from the casa rural would be picking them up in thirty minutes.

“Wow, it’s lucky you met that man; we have perhaps encountered our first Camino angel,” Bert said. “After hearing so much about how the Camino will provide an angel when you need one, I was beginning to wonder if we were scaring angels away. But he appeared, right when we were getting desperate.”

Helen laughed, greatly relieved things seemed to have gotten sorted out.

“Now that our lodgings are settled, I am reminded that in addition to being tired and hot, I’m hungry too,” she said.

They had found no place along the way to get lunch, and dinner was nowhere in sight. Bert decided to go back to a tienda—they had passed it just as they got to town—to get them some basic supplies to assuage their crying bellies. He liked their ‘tienda picnics’ with cheese, bread, chorizo, wine, and when they could get them, little plastic packages of green olives too. The packages read aceitunas con huesos or aceitunas sin huesos—literally olives with or without bones. While some American olives have pits, it appeared that in Spain they have bones.

Bert congratulated himself for having thought to bring along a fishing knife superbly adapted to preparing little feasts, with a minimum of cleanup required. Of course they never would have left home without a corkscrew.

He easily found everything he wanted in the tiny store, with one exception. He noted that the only loaf of bread visible was far too big. Not only was it too much for them to eat in a day or two, but it was too long to fit in his pack. Thinking the store might have some supply of bread out of sight, he asked the woman behind the counter if she had a small loaf of bread--tiene una pequeña pan? She shook her head, and Bert worried that she had not understood him. But unruffled, and undaunted by Bert’s poor Spanish, she took down the loaf, ripped off one end, and handed it to Bert. Apparently he was the one who didn’t understand. He paid and hurried out, not wanting to miss the promised ride to the other town and its inn.

When he got back to the square, the vehicle from the casa rural had not yet arrived. Helen was chatting with some other people and told him a French couple they had met before were also waiting for a lift to El Molino. They leaned their packs against the front of an albergue and waited next to them in the thin band of shade cast by the building. Too weary, they made no attempt to strike up further conversations with the other hikers crowding the little square. The time for socializing might come later, when and if they had rested a while.

From the number of people lounging in the hot square, Bert concluded that the local albergues were not only full, but were probably lacking in indoor seating. Why else would so many people be spending the afternoon draped on steps in the sun-drenched village square? They had passed other albergues where people were hanging around, often in uninviting, starkly basic courtyards. Other times when it was raining they had passed albergues where, peering inside, they saw people sitting on bunks in dark, dank-looking rooms. The image of what might lie ahead was troubling, but there seemed to be no other choices.

He was only too aware that they were at the mercy of the Camino when it came to getting someplace to stay for the night. Earlier a pilgrim had told them that giving yourself up to the Camino and learning to joyfully take what it offers you is one of its greatest gifts. Waiting for a ride that might or might not show up didn’t seem like a gift just then. On the other hand, what Bert had seen in Hornillos was unappealing, and he was not altogether unhappy that the town was unable to accommodate them. He hoped they would do better by getting a second chance.

In the promised thirty-minute waiting period a few vehicles—one car, two small delivery trucks, and a farm tractor to be exact—entered the square, and kept going. Perhaps forty-five minutes had elapsed when a car stopped in the small square. Getting out, the young man said, “El Molino?”

Bert, Helen, the French couple, and two other people stepped forward. This was clearly a problem; there were too many of them. The small car could only barely accommodate four extra people with their packs and other gear, and fitting in six was beyond imagination. The man said something in Spanish about expecting to pick up four people. He was obviously agitated, trying hard not to make eye contact with any of them, probably fearing that might indicate they should climb in.

Getting out his cell phone to call the inn, he apparently experienced the same problems Helen had encountered with the Blackberry—first no answer, and then twice his calls were dropped before he had gotten the needed information. The French couple, clearly impatient, put their backpacks in the open trunk, apparently expecting this to make a difference in their priority for transport.

Bert and Helen held back, however. It seemed clear that the man was not going to act without further instructions. Finally he got through and learned the names of the people he was to pick up. He asked Bert and Helen and the French couple—the man and woman—to get in the car. The others—two French women—were out of luck, but apparently in the queue and would be picked up later.

The trip to the Casa Rural El Molino convinced Bert that the guidebook had been guilty of a double exaggeration in reporting that it was in a nearby village. He guessed they must have traveled at least twenty miles over a patchwork of rural roads to reach their destination. Moreover, the place was far out in the countryside, with no village anywhere nearby. Even if they had gotten directions and could have found their way, it would have taken them a very long day to walk from Hornillos to El Molino.

Once out of the car, they discovered that the place was crowded. Following some initial confusion about what to do with them, a young woman who Bert never saw again led the two couples to their rooms. It soon became clear why they had had such difficulty in getting through and then getting there. El Molino was hosting a huge family reunion with at least fifty attendees, and the staff was obviously overwhelmed. The driver who had picked them up, they learned, was a volunteer pressed into service when no one else was available. So they had a reasonable explanation for the difficulties they had encountered, and these were soon forgotten when they took measure of the inn.

Living up to its name, it was obviously an old mill, with a stream and a millrace running under the building. Ducks and geese stood on the banks. Bert imagined that the grounds must have been beautiful at a different time of the year, but right now they were covered by great accumulation of the cottony seeds from the nearby grove of poplar trees. The messy debris looked like snow. It was on the patio, the tables, the chairs, the lawns, and driveways. The waterways were clogged with several inches of soapy-looking foam.

The inside of the old mill had been extensively remodeled. Their room had all modern conveniences and was uncommonly large for a European lodging. They had a pleasant sitting room shared with several other rooms and access to a keg dispensing free beer. This they guessed was at the beneficence of the family reunion, rather than the inn. Spanish and French were mostly spoken, but they did get to listen to some painful English.

They were sitting in the large common room with the impatient souls who had thrown their packs into the open trunk in Hornillos. The man was on his cell phone trying to make room reservations for the next day. He obviously spoke no Spanish and apparently the innkeeper on the line spoke no French. English was the possible second choice for each. The Frenchman’s was the most atrocious English Bert had ever heard. Somehow he seemed to have gotten the notion that it was appropriate to insert a “hello” after every second or third word. Bert thought the man might have confused the word “hello” with “okay.”

“Hello, hello. Je veux . . . une chamber, hello. Avec toilet, hello. Tomorrow, deux persons, hello? Je ne comprends pas, hello! Pour two . . . two personnes . . . Hello!!”

It was ludicrous, amusing, and horrifying. Bert looked at Helen. She looked away so she wouldn’t start to laugh out loud.

Toward evening the wind picked up and a thunderstorm appeared to be rolling in. The dozens of participants in the family reunion had been seated at outdoor tables and chairs in the grove of poplars not far from the building. Some left well before the storm hit, while others waited until the last minute. When the rain did begin to come down hard, the few holdouts fled. The family reunion was over, and the inn began to return to normal.

Dinner wasn’t until nine o’clock, so they read for a while, trying to pick up the plots of the paperbacks that had languished in their backpacks for days.

When the dinner hour finally arrived, with other guests they filed into a large dining room with a long table. It ultimately seated the two of them and thirteen other guests. The French couple and the two French women who had to wait in Hornillos for the second shuttle sat at one end. Helen was able to speak with them with her passable French, but was unable to keep up with their conversation. She knew better than to try to talk to the man in English!

At the other end of the table were five Germans, including a man they had chatted with earlier. He spoke English, but it was clear that he enjoyed talking with the other German speakers more than working to converse with the two of them. They were near the middle of the table, as were two Spanish couples. It appeared to Bert that this evening they would need to rely on each other for conversation.

He soon discovered otherwise. The man who sat across from Bert and Helen introduced himself as Oscar. His English did not come easily to him, and his three companions apparently did not speak it at all. Obviously friendly, outgoing, and energetic, Oscar was not to be deterred from making new friends by something as trivial as a language barrier. Using his limited English and patient Spanish that Bert found relatively easy to follow, he told them his story.

The other Spanish man, who sat next to Bert, was his brother Ernesto, he said. They were from Sevilla. They were walking the Camino from Burgos to Santiago together with their wives, who had never met before two days ago, when their adventure had begun. The brothers looked very much alike. They had close-cropped hair, round faces, and bushy black eyebrows. But what made them so resemble each other was their round, sparkling, brown eyes. Flashing eyes seemed to Bert a funny feature to note in two grown men, but there they were, undeniably calling attention to themselves.

Ernesto may have gotten a wordless cue from his brother, or perhaps understood more English than he let on, because he turned, gave a big smile, and shook hands with Bert, finishing with a pantomime introduction of his wife. Oscar belatedly introduced his wife also. She reached out to shake hands and seemed as eager to be friendly as her husband, but she gave no indication of understanding the first word of English. She remained on the fringes of the conversation. Oscar patiently kept her informed of the drift of the conversation.

As they chatted, the first offerings of what was to be a multicourse meal were served, beginning with bread and olive oil. Immediately Bert understood that this was not to be the typical dinner. Instead, it was a real Spanish meal—the kind of meal the locals enjoyed while eating and talking long into the evening. An early course included fried strips of pork that the Spanish called pancetta. He recognized it as only a distant relative of the famous Italian bacon of the same name. Instead it was “side pork,” “sow belly,” or “white bacon,” a staple of country cooking in America, long in disfavor because of its artery-clogging qualities.

Ernesto was gray-headed and looked older than Oscar, and Helen asked whether he was Oscar’s big brother.

“Once años,” said Oscar.

“Eleven years,” said Helen.

Oscar nodded. In a remarkable combination of languages and gestures, he made known that he and his brother had not seen each other for almost twenty years. He had been a teenager when his brother joined the army, and after the army Ernesto had gone to live in Venezuela. He had returned to live in Spain recently, and through relatives the brothers had gotten in touch. Realizing that they had been separated for almost their entire lifetimes, they felt they had much to catch up on. They decided to walk the Camino together to get reacquainted. So far they had already discovered they had much in common and were obviously enjoying each other’s company.

Their wives weren’t sure that the Camino was for them. Indeed, the brothers were walking and planning to continue all the way to Santiago, but the wives were traveling by car. It wasn’t clear to Bert whether they would be following their husbands along the way and joining them from time to time or whether they were just dropping them off. He did pick up that the intention was that the wives would be getting to know one another also.

Perhaps they are, thought Bert, but it is clear that they are not enjoying the experience nearly as much as were their husbands.

Oscar pointed out a framed poster on the wall behind Bert and Helen that they hadn’t noticed. It was an advertisement for an American movie about the Camino called The Way. They had heard of it and had even seen a trailer. They didn’t know until Oscar told them, however, that the cast and crew had stayed in this very inn during filming. Bert resolved to see the film when it was released in the United States, hoping to catch scenes of El Molino and possibly other familiar sights from the Camino.

Oscar wasn’t finished. They had remarked about the food, and he had some dining suggestions for them. Most of his suggestions seemed to be local specialties, and neither Bert nor Helen could understand what he meant. He asked whether they had paper with them, and Helen took out a small notebook she carried. He got his wife to produce a pen, and he wrote down some things they should ask for when the opportunity arose. When Bert asked for the meaning of one word, he drew a little picture of a goat, and said joven, indicating that the meat in the dish was from a young goat.

The food and wine kept coming, then cheeses, and then a sampler of aperitifs. Just after eleven the meal was declared to be finished, and everyone got up to leave.

Thinking about the chaotic arrangements that had gotten them to El Molino, Bert was a bit concerned about the following morning and how they would get back on the Camino. Helen had overheard a discussion between one of the French women and the owner’s wife concerning arrangements for the morning. She said that from what she could make of the exchange, it appeared that the French couple wanted to be delivered to Hornillos at seven, and the other woman was offering them transport at nine. Helen hadn’t heard the resolution of this apparent conflict, but she told Bert she doubted that the French woman would be leaving at seven. Bert would also have preferred seven, but decided that eight would be fine. If they didn’t leave until after nine, however, they might have trouble making it to Castrojeriz in good time. They discussed it and decided they would be ready to depart at eight, but at the same time be ready to go with the flow. They surely wouldn’t be walking back to Hornillos.

As things developed the next morning, they had finished breakfast, paid their remarkably inexpensive bill, and were ready to leave for Hornillos at ten before eight. They waited only a few minutes before the owner showed up in an ancient and obviously much used Range Rover and sped them off to Hornillos.

Despite the lateness of the night before, Bert felt refreshed. They were ready to begin walking as soon as they were discharged into the same square where they had been picked up a scant seventeen hours before.

Bert began the conversation once they were out on the open road.

“Meeting Oscar and Ernesto for some reason reminded me of my own family. It struck me that I know my brother and sister about as well as the Spanish brothers knew each other. I haven’t exactly lost track of them. I think I could get in touch with them if necessary. But I haven’t seen either of them in years. I can’t imagine we would have much in common. On the other hand, who’s to say? Oscar and Ernesto seem to be getting along all right, despite the significant age difference. I know a reunion of that kind with my siblings will never happen, but the brothers did make me think about them.”

“Maureen, Donna, and I were quite close when we were growing up, even though I am a couple of years older and only a half-sister. We’re in touch mainly by e-mail. I think we have a good relationship, but we aren’t all that close any more. Their lives have been different from mine. They’ve had long marriages and children. Both of them went to work when their kids started school. They have good jobs, but you wouldn’t really say they have careers like ours. I like both of them, but we haven’t had many shared experiences since our childhood days. I was a little surprised that they seemed to be interested in our Camino.”

“Do you see them often?” Bert said, finding many things having to do with family dynamics unfamiliar, and therefore mildly interesting.

“I see each of them maybe once a year, on average. Weddings, funerals, graduations usually provide the reason. Lacking one of those events, I try to make an effort to visit. It’s been a bit harder since I’ve been at the refuge than when I had an eight to five job. I’m both tied down and far from the main travel hubs. You’ve touched a tender spot here. I wish I could be a better sister to them. I may be wrong, but I think if I tried harder I might still be helpful to them, like when I was their big sister.”

“Well, maybe you can feel better now that you’ve discovered someone who is far worse at holding up his end of sister- and brotherhood than you are,” said Bert, hoping to end the discussion on a lighthearted note.

Helen seemed to want to move on to another topic also.

“I’m glad that all the albergues, hostals, hotels, and the like in Hornillos were completo,” she said. “El Molino was a real experience.”

“I agree. We saw the old mill, had a real Spanish meal, met the brothers, slept in nice beds, and we got to speed at a hundred kilometers an hour over crumbling Spanish country roads in a rickety Range Rover. We enjoyed the first several of our experiences and survived the last.”

“I really liked Oscar. Both brothers. I liked them both. They seemed so happy to have rediscovered each other. Maybe I should get my sisters to come on the Camino with me sometime. Silly thought! They’re much too busy, I doubt they enjoy walking, and what would we talk about?”

Bert looked over at her, curious about her unusual mention of her sisters. But she was looking off to the side and he didn’t catch her eye.

“Back to my first thought,” she said. “After meeting Oscar, I don’t think I’ll ever again be reluctant to talk with somebody just because I’m not good at their language. If there had been other English speakers, we would have had to talk with them, and that probably wouldn’t have been any fun at all.” “Yeah, it was a good time,” said Bert. La Noche Blanca and then El Molino—both had been special, almost magical experiences. Maybe the Camino was being kind to them, and maybe more good things awaited them.

“And the idea,” said Helen, interrupting his thoughts. “Imagine the idea of using a walk on the Camino as a way of reconnecting with somebody you haven’t seen in a long time. I wonder . . . how could anybody ever come up with a preposterous idea like that?”

This time she looked toward him just as he was looking to her.

“I wonder,” said Bert, noting the teasing in her eye.

The Seeker

Castrojeriz to Fromista

Wednesday, June 1

Bert was feeling good as they left Castrojeriz and headed toward Fromista. Helen was still fussing with her pack from time to time. But he felt his body getting almost used to the walking. They stopped a couple of times for coffee and to rest, arriving on the outskirts of Fromista weary, but not distressed. They had first climbed, and then descended a steep hill. It had been a long walk—nearly sixteen miles—but the last stretch had been easy, along a canal.

Two features struck Bert about today’s walk: the beauty of the wide vistas on the Meseta, and the strength of the wind that relentlessly blew across them. The scrubby elm trees planted along the canal permanently leaned to the south. Bert thought he might lean permanently to the left too if he had to walk with the wind against him like this for many days in a row.

Still, the sky was dramatic. Clouds, some of them ominously dark, rushed across the bright blue background, pushed by the powerful air. Something about today’s sky looked Spanish to him, probably because El Greco might have painted it. Perhaps for the first time, Bert thought that maybe he could really walk five hundred miles. The notion surprised him when it crept into his consciousness.

Helen interrupted his thoughts. “There’s an eleventh century church in Fromista that has been restored to its pure Romanesque roots, simple and unadorned. Also, my guidebook mentions another church it says is worth a visit.” She was consulting the book as they walked, well attuned to sights along the way.

Bert could not be less enthusiastic about visiting another church. He was ready for a break after all these miles, and one that involved a large beer appealed to him much more than a church visit. His feet and legs might be getting used to walking, but nevertheless they were tired—no blisters, but plenty of soreness. He hoped she would forget any church visits by the time they got to town, but doubted she would.

Coming to the end of the canal, they walked on a concrete catwalk over a spillway. Descending a short hill, they entered the town. When the first church appeared in the middle of a small square, Bert noted that it was not topped as most seemed to be, by at least one large stork nest. He knew they would be visiting it.

Being in churches—not the museum-like cathedrals, but those in everyday use—continued to afflict him with a strong sense of unease. It made him feel like an imposter. Churches are meant for people who use them for worship, he thought, and not as tourist attractions. What if some true believer challenged him in a church and asked him what he was doing there? The challenger might identify the intruder—him—as someone looking for a freak show, and that might not be far from the truth. Why would he be there if not to gawk at curious objects related to strange rituals? Even worse, oftentimes there were people in the churches who were praying or in some kind of spiritual reverie, and observing them made him feel like a voyeur—looking in on something intensely private and not meant for the sightseer.

Helen liked visiting churches. He knew she would take her time, squinting in the dim light at the guidebook and learning of the significance of the special features, often statues or paintings, and occasionally the resting places of notable personages. He thought she was no more a churchgoer than him, but she seemed immune to the kind of sensitivities that caused his extreme discomfort.

Suddenly it hit him. He felt like an imposter and a voyeur much of the time on this whole trip. Despite his having read that pilgrims were originally thought of as foreigners or wanderers, he couldn’t shake the sense that the Camino was a pilgrimage trail. Nor the feeling that a pilgrimage is primarily a religious experience.

Even thinking of himself as a wanderer rather than a pilgrim, Bert continued to be put off by all the religious touchstones. To him even the concept of spirituality was outside the realm of reason, and was to be classified with sorcery, witchcraft, and other remnants of the Dark Ages.

Nothing along the Camino so far had diminished his puzzlement; he felt surrounded by ideas and concepts that strayed over the edge of rationality. Helen seemed untroubled by the strangeness. She told him his sensitivity was misplaced but hadn’t been able to explain this in terms he could accept. Communication between them had never been flawless, and this was another disconnect. How could she be so accepting of something she couldn’t adequately explain?

Outside the church, Bert steeled himself for the awkward moments inside. Trying not to be obvious to the point of rudeness, he would look for the earliest opportunity to leave the stuffy surroundings and regain the freedom of the open air.

The restored church was small. His mind was eased somewhat by the fact that this wasn’t one of those great gaudy Gothic or Baroque edifices with rich trappings and ornate treatments that he found off-putting, even as he admired the art of a place like the Burgos cathedral. This was part of his confusion. He had a gut feeling that whatever spirituality was about, it had little to do with the jewels, gold leaf, and over-the-top ornamentation, the kinds of material riches he had seen in abundance in churches. But obviously there were many who felt differently; otherwise why would they have stocked their churches with works of art? And why would churchgoers be so captivated by them?

As they stood by the entrance, Helen was again reading. “Though relatively small, this church has three aisles. Most notable of its parts is the right or south apse, which was remodeled in the Baroque style in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its claim to fame is the highly regarded and hauntingly lifelike statue of Santiago Matamoros, rendered in the eighteenth century by Brother Marcello of the nearby Monastery of Saint Julien. The remainder of the church is unremarkable, although it has been heralded by a few purists as an outstanding example of the Romanesque architectural tradition. It contains no artwork or other features of particular note.”

Bert had seen the statue of Santiago Matamoros above the entrance to the cathedral in Logroño. The name, he learned, translates in English as Saint James the Moorslayer. The statue showed the saint as he was reported to have miraculously appeared on several battlefields in the protracted war against the Moors. Decked out in a suit of armor, and mounted on a large horse, he was in the act of swinging a huge sword. Beneath the horse’s hooves were the headless bodies and severed heads of the unfortunate Moors. Perhaps Saint James in the statue in this church would be lifelike, but what impressed Bert in the other statue he had seen were the lifelike—or perhaps deathlike was a more apt description—expressions on the severed heads. The effect was disturbing and in a way, he thought, almost obscene.

Not wishing to experience this Moorslayer up close, Bert resolved to stay in the back of the church, hoping to find a place in the shadows where he could wait for Helen to finish her self-guided tour. It turned out that the door they entered through was at the side of the building, so once inside, Bert departed from Helen and quickly made his way toward the back, trying his best to be invisible to the two people he saw sitting in the pews. Of course, he stubbed his toe on a kneeler, making a noise that echoed through the church, and causing at least one of the apparent worshipers to look his way. Grateful that he hadn’t reflexively let out a real swear word, he managed to keep the “damn” he nearly uttered under his breath.

When he reached the rear of the church, he was pleased to discover that it was quite dark, as he had hoped. This church was almost intimate, and he at first thought he might feel more like an intruder here than in one of the big, museum-like churches. Somehow he felt unaccountably comfortable here in the shadows, however.

He took measure of the structure. He found the front of the church attracting his attention. Most of the light was coming from tall, clear windows at the front. They bathed the interior in soft white.

The statue of the Moorslayer and the remodeled part of the church that the guidebook had cited were out of sight, and Bert realized that it was the unspoiled, but “unremarkable” Romanesque part that he was viewing. Keying on the word “unremarkable,” he was bemused. Something was wrong with the guidebook or with him, because to his mind this was clearly the most remarkable church he had ever visited. They had seen several scenic vistas in the Spanish countryside. But setting them aside, in some inexplicable way this was the most remarkable place and remarkable scene he’d experienced on the trip so far. How could that be?

Almost free of adornment, the building itself spoke eloquently to him of its purpose; the tall rounded arches enclosing the space. Yes, that was it, the space. It was a space lofty enough and beautiful enough to accommodate something. He supposed that something must be the towering faith of its builders, or maybe of the faithful it was intended to serve.

Bert had a strange desire to talk to these men who almost a thousand years before had built the church. Was he right in guessing their intention? But of course they were long gone, and he doubted he would ever be able even to find out who they were, because it seemed likely that their handiwork was the only trace left of them. Unquestionably lacking their faith, he still felt that whoever they were, they had somehow found a way to speak to him, to deliver a millennium later—a remarkable forty or fifty generations later—the precise message they must have intended—hoped, perhaps—to convey. He understood nothing about what they knew and of course did not and would not share their faith, but they had told him eloquently of their devotion!

Bert didn’t move, and he realized he was no longer in any hurry to get outside. He had encountered something unexpected and wasn’t quite ready to let go of it, at least until he knew what it was. He thought he understood better, but his experience was not the satisfied “ah ha” reaction one gets upon having found the answer to a vexing question. Indeed, this wasn’t something he could readily explain. This instead was something different, almost disturbing.

Helen was apparently still in the other part of the church. But he saw movement. His eyes followed an old woman who had been sitting in a pew when he came in. She got up as if to leave and knelt briefly, but didn’t go directly to the door as he expected. She instead went to an iron rack in which perhaps twenty candles in little glass cups were arrayed. Taking an object from beneath the rack, she used it to light one of the candles, adding its light to that of two already burning. Then she left, pausing by the door to do something. Bert’s mind was in overdrive. He returned his gaze to the church. Yes, it had a strange allure; most certainly a strangeness.

He saw Helen at the front of the church. She must have examined the art objects, and was now making a more cursory observation of the other features of the church. It would soon be time to leave. Perhaps his autopilot kicked in. Without really thinking about it, Bert moved to the candle rack where he had seen the woman. He took a taper from underneath and lit another candle, taking a light from the flame of the one the woman had lit. He noted a coin slot on the front of the metal rack and, fishing in his pocket, found a brass half-euro coin. Dropping it in the slot, his contribution was recorded by a loud clanking sound that reverberated through the emptiness of the church.

Ignoring the disturbance he had caused, he made his way outside. He had no logical narrative for what he’d just done.

Helen came out a few minutes later. “I saw you lighting a candle in there,” she said.

Bert acknowledged with a nod that he had indeed done so, but offered no explanation.

“Why did you do that?” She said this impatiently, as if she believed he had a ready answer but was holding out in order to vex her.

“I don’t know,” Bert said, wishing he had an answer for his own bewildering, but still intriguing, experience.

Could Helen see the confusion that must be registering on his face? He could read nothing from the look on hers. The moment was short-lived, because three noisy teenage boys came bounding up.

“¿Alemans?” said the apparent leader.

“No. Norteamericanos,” replied Bert.

“Have a nice day,” the spokesman called after them as they started down the trail.

__________

Sunday, June 5 9:22 PM

To: [email protected]

Cc: [email protected], [email protected]

From: [email protected]

Subject: Camino Report #4

Now we’re in the mid-sized town of Sahagún. We took a rest day in Burgos, as Helen reported. Burgos is a beautiful city. After 14 days of walking, my body felt deserving of the luxury. I would have been sending more updates, but we haven’t been near a computer, and I haven’t had the energy to go out looking for one. Anyway, it’s been a while, so I’ll try to rattle off the highlights.

After Burgos we had generally pleasant walking, still on the Meseta and still liking it. At one point we passed the impressive ruins of the fifteenth century convent of San Anton. Tall ruins of the convent walls remained standing and we rested in their shade. There were large openings high above us where windows would have been on a second story of the building. Clouds floating in a rich blue sky were framed in the window spaces. The Camino was along a country road at that point and the road ran right through the ruins.

Not long after that we were walking under the ruins of a hilltop castle near the town of Castrojeriz. The guidebook said the hill had been fortified since pre-Roman times, but the present castle dates from the ninth century. We were too tired to walk up the hill to get a better look, and from the ground it looked like little more than crumbling walls.

We had more walking through picturesque countryside, often enjoying vistas where we could see the gravel road snake ahead of us for miles. That was especially true just after Castrojeriz. We climbed a steep hill coming out of there. When we crested the hill, the vista was spectacular, consisting of many rolling miles bathed in the greenest wheat. The steep downslope was a real challenge. We passed a huge monastery turned into a luxury hotel. Wheat fields dotted with occasional bright red poppies were almost always with us as we walked, as were cordial hikers at our overnight stops.

Sahagún is an interesting town with more ruins of monasteries. One surprise it has given us is a look into family life that we never would have imagined. Sitting around the plaza mayor, the main square, we saw the open part of the square filled with young children, running, screaming, and propelling wheeled vehicles ranging from tricycles to skateboards. Their parents were sitting at tables in sidewalk cafés around the square, chatting and sipping on drinks. At nine o’clock, more or less, with daylight still abundant, all cleared out, presumably heading home for the evening meal. So in Sahagún, at least, the village square combines as a playground and meeting place for young parents. We noticed it too in Burgos, but thought it might have been that many people were in town for the festival. Now we think plazas are probably always community gathering-places.

Today the center of Sahagún filled up with vendors. At first we thought it was a farmers’ market, but most of the stalls were selling ordinary merchandise like handbags and tee shirts. Despite all the people around, for some reason we haven’t discovered, we have not had good luck finding our evening meal. Helen thinks this town may not be one of the major stops on the Camino, and indeed, we have seen relatively few hikers here. We couldn’t find a peregrino meal tonight, but got sandwiches—thickly piled slices of Iberian ham encased in crusty bread—in a bar. They were good, and a nice break from the routine.

In addition to Internet access, one of the amenities here in Sahagún is a pharmacy, where we loaded up on remedies. Helen got two kinds of patches useful in treating or preventing blisters. Neither of us has gotten a blister yet, but we are both suffering from non-blister sore spots on our overstressed feet. I got some 300-milligram ibuprofen capsules. They help to dull the pain in my left knee. Also, the knee gave out yesterday, and they take care of the couple of bruises I got in the fall.

I expect we’ll be off to an early start on the trail tomorrow.

By the way, I’ve noticed a big falloff in the Task Force’s e-mail traffic lately. Can it be that now that I’m on leave, everybody else has given themselves permission to enjoy a bit of down time?

Bert

P.S. Regarding the late timing of the festival of lights in Burgos and dinner time in Sahagún: Most of Spain is at the same longitudinal zone as Great Britain, and on that basis should be in the Greenwich (GMT) Time Zone. It is, however, officially in the Central European Time Zone (GMT+1), presumably to be more in sync with its continental neighbors. As a result, at this time of the year darkness doesn’t fall until nearly 10 o’clock. Maybe that’s why they eat dinner so late.

__________

Sunday, June 5 9:23PM

To: [email protected], [email protected]

From: [email protected]

Subject: People on the Camino

Maureen and Donna,

Bert and I each snagged a computer tonight in this Internet café. In the past we have been lucky to get one, rather than two at one time. I am sure he will be giving the description of the trail and the towns. I thought you might like to know a bit about some of the people we have met. He is more into the environment than the people, so I doubt he will mention any of them. But to me there have been many interesting folks. We met a young woman, in her thirties I’d guess, who told us that last year she’d walked the whole Camino, alone, in the winter. She loved the quiet of the snow-covered trail and the fact that she was usually the only one in the albergue at night. It made her feel she could commune with the pilgrims of medieval times.

While Bert washed clothes outside an albergue one afternoon, I chatted with a French woman who seemed about my age. I was doing pretty well with my French. She had gotten tired along the trail and caught a bus from the last town before that one, but her husband had decided to walk the distance. He arrived after we’d been talking for thirty minutes or so. In French she told him that I spoke French but not very well, so he should speak slowly. Of course, I understood every word she said and when we all realized it, the three of us had a great laugh. I explained the joke to Bert when he saw the scene and came to investigate. We have seen that couple twice since and become pretty good friends. Their English is about on the level of my French, so we switch back and forth, especially when Bert’s with us.

One final couple to share, for now—bikers! I suppose I should call them “cyclists,” because they drive bicycles, not Harleys. As much as we have come to fear people on bikes, we ended up at a dinner table with a couple from England who started their Camino in Rome! I had asked where they stayed the night before, just as small talk. But the town they mentioned was about fifty miles behind us. I think they enjoyed springing surprises like that on hikers because just as I was about to say “Where?” they laughed and told us they were riding bikes. They mentioned how hard it is to find routes that are not along the highways and how hard they try not to scare hikers. It gave us a new perspective, although did not lessen my fear of their bikes very much.

We have to feed a euro coin into these computers every fifteen minutes. My time and euro coins are used up, so I’ll close for now. Hasta pronto.

Helen the Hiker

Two features struck Bert about today’s walk: the beauty of the wide vistas on the Meseta, and the strength of the wind that relentlessly blew across them. The scrubby elm trees planted along the canal permanently leaned to the south. Bert thought he might lean permanently to the left too if he had to walk with the wind against him like this for many days in a row.

Still, the sky was dramatic. Clouds, some of them ominously dark, rushed across the bright blue background, pushed by the powerful air. Something about today’s sky looked Spanish to him, probably because El Greco might have painted it. Perhaps for the first time, Bert thought that maybe he could really walk five hundred miles. The notion surprised him when it crept into his consciousness.

Helen interrupted his thoughts. “There’s an eleventh century church in Fromista that has been restored to its pure Romanesque roots, simple and unadorned. Also, my guidebook mentions another church it says is worth a visit.” She was consulting the book as they walked, well attuned to sights along the way.

Bert could not be less enthusiastic about visiting another church. He was ready for a break after all these miles, and one that involved a large beer appealed to him much more than a church visit. His feet and legs might be getting used to walking, but nevertheless they were tired—no blisters, but plenty of soreness. He hoped she would forget any church visits by the time they got to town, but doubted she would.

Coming to the end of the canal, they walked on a concrete catwalk over a spillway. Descending a short hill, they entered the town. When the first church appeared in the middle of a small square, Bert noted that it was not topped as most seemed to be, by at least one large stork nest. He knew they would be visiting it.

Being in churches—not the museum-like cathedrals, but those in everyday use—continued to afflict him with a strong sense of unease. It made him feel like an imposter. Churches are meant for people who use them for worship, he thought, and not as tourist attractions. What if some true believer challenged him in a church and asked him what he was doing there? The challenger might identify the intruder—him—as someone looking for a freak show, and that might not be far from the truth. Why would he be there if not to gawk at curious objects related to strange rituals? Even worse, oftentimes there were people in the churches who were praying or in some kind of spiritual reverie, and observing them made him feel like a voyeur—looking in on something intensely private and not meant for the sightseer.

Helen liked visiting churches. He knew she would take her time, squinting in the dim light at the guidebook and learning of the significance of the special features, often statues or paintings, and occasionally the resting places of notable personages. He thought she was no more a churchgoer than him, but she seemed immune to the kind of sensitivities that caused his extreme discomfort.

Suddenly it hit him. He felt like an imposter and a voyeur much of the time on this whole trip. Despite his having read that pilgrims were originally thought of as foreigners or wanderers, he couldn’t shake the sense that the Camino was a pilgrimage trail. Nor the feeling that a pilgrimage is primarily a religious experience.

Even thinking of himself as a wanderer rather than a pilgrim, Bert continued to be put off by all the religious touchstones. To him even the concept of spirituality was outside the realm of reason, and was to be classified with sorcery, witchcraft, and other remnants of the Dark Ages.

Nothing along the Camino so far had diminished his puzzlement; he felt surrounded by ideas and concepts that strayed over the edge of rationality. Helen seemed untroubled by the strangeness. She told him his sensitivity was misplaced but hadn’t been able to explain this in terms he could accept. Communication between them had never been flawless, and this was another disconnect. How could she be so accepting of something she couldn’t adequately explain?

Outside the church, Bert steeled himself for the awkward moments inside. Trying not to be obvious to the point of rudeness, he would look for the earliest opportunity to leave the stuffy surroundings and regain the freedom of the open air.

The restored church was small. His mind was eased somewhat by the fact that this wasn’t one of those great gaudy Gothic or Baroque edifices with rich trappings and ornate treatments that he found off-putting, even as he admired the art of a place like the Burgos cathedral. This was part of his confusion. He had a gut feeling that whatever spirituality was about, it had little to do with the jewels, gold leaf, and over-the-top ornamentation, the kinds of material riches he had seen in abundance in churches. But obviously there were many who felt differently; otherwise why would they have stocked their churches with works of art? And why would churchgoers be so captivated by them?

As they stood by the entrance, Helen was again reading. “Though relatively small, this church has three aisles. Most notable of its parts is the right or south apse, which was remodeled in the Baroque style in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its claim to fame is the highly regarded and hauntingly lifelike statue of Santiago Matamoros, rendered in the eighteenth century by Brother Marcello of the nearby Monastery of Saint Julien. The remainder of the church is unremarkable, although it has been heralded by a few purists as an outstanding example of the Romanesque architectural tradition. It contains no artwork or other features of particular note.”

Bert had seen the statue of Santiago Matamoros above the entrance to the cathedral in Logroño. The name, he learned, translates in English as Saint James the Moorslayer. The statue showed the saint as he was reported to have miraculously appeared on several battlefields in the protracted war against the Moors. Decked out in a suit of armor, and mounted on a large horse, he was in the act of swinging a huge sword. Beneath the horse’s hooves were the headless bodies and severed heads of the unfortunate Moors. Perhaps Saint James in the statue in this church would be lifelike, but what impressed Bert in the other statue he had seen were the lifelike—or perhaps deathlike was a more apt description—expressions on the severed heads. The effect was disturbing and in a way, he thought, almost obscene.

Not wishing to experience this Moorslayer up close, Bert resolved to stay in the back of the church, hoping to find a place in the shadows where he could wait for Helen to finish her self-guided tour. It turned out that the door they entered through was at the side of the building, so once inside, Bert departed from Helen and quickly made his way toward the back, trying his best to be invisible to the two people he saw sitting in the pews. Of course, he stubbed his toe on a kneeler, making a noise that echoed through the church, and causing at least one of the apparent worshipers to look his way. Grateful that he hadn’t reflexively let out a real swear word, he managed to keep the “damn” he nearly uttered under his breath.

When he reached the rear of the church, he was pleased to discover that it was quite dark, as he had hoped. This church was almost intimate, and he at first thought he might feel more like an intruder here than in one of the big, museum-like churches. Somehow he felt unaccountably comfortable here in the shadows, however.

He took measure of the structure. He found the front of the church attracting his attention. Most of the light was coming from tall, clear windows at the front. They bathed the interior in soft white.

The statue of the Moorslayer and the remodeled part of the church that the guidebook had cited were out of sight, and Bert realized that it was the unspoiled, but “unremarkable” Romanesque part that he was viewing. Keying on the word “unremarkable,” he was bemused. Something was wrong with the guidebook or with him, because to his mind this was clearly the most remarkable church he had ever visited. They had seen several scenic vistas in the Spanish countryside. But setting them aside, in some inexplicable way this was the most remarkable place and remarkable scene he’d experienced on the trip so far. How could that be?

Almost free of adornment, the building itself spoke eloquently to him of its purpose; the tall rounded arches enclosing the space. Yes, that was it, the space. It was a space lofty enough and beautiful enough to accommodate something. He supposed that something must be the towering faith of its builders, or maybe of the faithful it was intended to serve.

Bert had a strange desire to talk to these men who almost a thousand years before had built the church. Was he right in guessing their intention? But of course they were long gone, and he doubted he would ever be able even to find out who they were, because it seemed likely that their handiwork was the only trace left of them. Unquestionably lacking their faith, he still felt that whoever they were, they had somehow found a way to speak to him, to deliver a millennium later—a remarkable forty or fifty generations later—the precise message they must have intended—hoped, perhaps—to convey. He understood nothing about what they knew and of course did not and would not share their faith, but they had told him eloquently of their devotion!

Bert didn’t move, and he realized he was no longer in any hurry to get outside. He had encountered something unexpected and wasn’t quite ready to let go of it, at least until he knew what it was. He thought he understood better, but his experience was not the satisfied “ah ha” reaction one gets upon having found the answer to a vexing question. Indeed, this wasn’t something he could readily explain. This instead was something different, almost disturbing.

Helen was apparently still in the other part of the church. But he saw movement. His eyes followed an old woman who had been sitting in a pew when he came in. She got up as if to leave and knelt briefly, but didn’t go directly to the door as he expected. She instead went to an iron rack in which perhaps twenty candles in little glass cups were arrayed. Taking an object from beneath the rack, she used it to light one of the candles, adding its light to that of two already burning. Then she left, pausing by the door to do something. Bert’s mind was in overdrive. He returned his gaze to the church. Yes, it had a strange allure; most certainly a strangeness.