|

You can read this section of the book here on screen, or use the buttons to download it as a PDF or Word file to read on another devise.

|

|

Second Wind on the Way of St. James

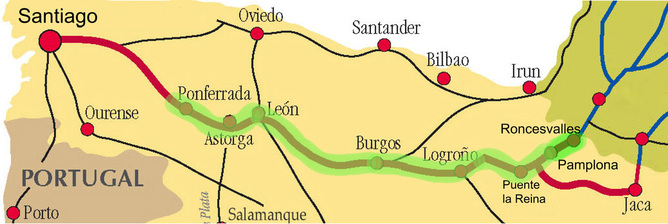

© 2013 by Russell J Hall and Peg Rooney Hall Published by: Lighthall Books P.O. Box 357305 Gainesville, Florida 32635-7305 http://www.lighthallbooks.com Orders: gem@lighthallbooks.com No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, either electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, except as specified by the authors. Electronic versions made available free of charge are intended for personal use, and may not be offered for sale in any form except by the authors. Excluded from copyright are the maps, which are based on the work of Manfred Zentgraf of Volkach, Germany. Like the original, our adaptations of his map remain in the public domain. Second Wind is a work of fiction. Many experiences of the authors on the Camino have inspired and informed themes of the book, but people and events depicted are products of the authors’ imaginations; any resemblance to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental. |

Episode 5

Stage Five:

Turning Points

Santa Catalina de Somoza to Ambasmestas

Love in the Afternoon

Santa Catalina de Somoza to Foncebadon

Tuesday, June 14

Bert’s ankle looked awful still, but he said it wasn’t bothering him most of the time, as long as he didn’t twist it too much on uneven ground. Helen was greatly relieved for both of them that it did not feel as bad as it looked. They had kept their distances short since the mishap, and he said it seemed to be healing, or at least not getting worse.

Walking out of Santa Catalina de Somoza, they passed through what for the most part is a ghost town. Perhaps half of the thirty or forty stone dwellings were complete ruins, and of those that were maintained or restored, few seemed to be permanently occupied. Helen noted that the restored houses seemed to all sport bright colored front doors, blue or green being the most popular, and had door knockers shaped like fists.

The two albergues appeared to be the only going concerns in the little settlement. The guidebook said that the place had a population of fifty, but Helen doubted the total could be close to that many.

The two-lane road was paved with bricks to the edge of town. Crumbling stone fences and walls lined it. Little white and pink flowers pushed through the rubble and climbed over the stones.

“Rock garden flowers,” Bert noted.

Where a door or window used to be, Helen sometimes could look through into a grassy space that used to be a room and see a big white multiflora rose bush or two. She had Bert take her picture in a former doorway where the lintel was so low she had to duck to stand in the space.

“I read that somoza in Latin meant ‘under the mountain.’ I can’t find it in my Spanish dictionary. But we’re sure surrounded by mountains,” Bert said as they left the paved road and started along a yellow dirt path.

Mountains were on every horizon except behind them, and they were continuing the gradual climb they’d experienced all day yesterday. On the walk to Santa Catalina, Helen had been fascinated that Astorga and the spires of its cathedral had remained visible behind them for most of the seven miles.

The path was straight, level, and well-maintained. Surprisingly, on one side it paralleled the paved and little used secondary road they had just left, and on the other side a gravel farm road. On most sections of the Camino they would have found themselves walking on one or other of these, and having a surface they did not need to share with cars and trucks or with farm tractors seemed an unlikely luxury—especially here where the parallel roads were practically unused. Concrete posts about three feet high with the Camino shell icon and sometimes also a yellow arrow on them marked the path. Where there were fields between the path and the paralleling roads, they often were outlined by stone fences.

Few other walkers were in sight, and most of the time Helen felt that the two of them were quite alone. Strange, she thought; I spend most of my life alone, but this feeling that Bert and I are the only people in the world is new, and different. I wonder if he has noticed it.

Her rare moment of sensing a shared solitude changed when they came across a couple sitting by the trail, enjoying a snack. He was perched on the stone fence and she sat on the ground with her back against one of the Camino markers.

“Come join us,” the blue-eyed woman said, smiling softly and broadly under a visor and holding out a plastic bag. “Look, we picked up some goodies in Astorga.”

From their accent, or lack thereof, Helen knew that they were surely North Americans—probably Canadians, she guessed.

Their times with the few Americans they had met on the trail so far, like Gwen and her husband Daryl, were particularly memorable. Helen thought that perhaps it was because of common experiences; if one mentioned a high school reunion, for example, the other would have some idea of its meaning, whereas it would likely draw a blank stare from a German or Spaniard. Of course, they hadn’t crossed the Atlantic Ocean to talk with other Americans, but their very rarity on the Camino increased the allure of occasionally meeting up with them.

"Thanks. What have you got? And where do you hail from?” Helen said when they reached the other couple.

“Have an apple. Oh, we’re from . . . You know, that’s a difficult question. We have houses in two different states. Uh, I hadn’t thought about it, but as things stand, neither can be described as our primary residence. I’ll spare you all the details. Let’s just say Florida, and leave it at that.”

“Well, we have that in common. Same answer from us. I’m Helen and I live in a small town on the Florida Gulf Coast. My friend Bert lives in one of the ‘burbs’ near Washington, D.C.”

Having thus broken the ice, they soon learned that the tanned, dark-haired, and somewhat more reticent Al and the fair-skinned, trim, and outgoing Margie were affable and easy companions. A few years their senior, they seemed to exude energy and good health, making Helen wonder whether they were like that all the time, or were just buoyed by being on the Camino.

Each finding a flat stone on the fence, Bert and Helen sat down with them, offering some of their dried apricots for the shared mini-picnic. The banter was mostly superficial. Where did you start? How long have you been walking? How did you learn about the Camino? Where are you headed tonight?

They were all going to Foncebadón, although they had set their sights on different hostals. Margie had booked them a private room, while Helen had accepted the last two spaces in the albergue she called, and they would be in a room for four. Bert proposed, and all agreed, that they would meet again when they reached their destination and would have a beer and maybe a pilgrim dinner together. Their new acquaintances resumed walking, while Bert and Helen rested a while longer.

A bit later the path joined one of the roads and brought them into the village of El Ganso, another abandoned looking town of crumbling stone fences and houses. Here they came upon the landmark Mesón Cowboy—the Cowboy Bar. Helen thought that the incongruous bar and its equally quaint neighboring café might spoil the mood for those who value authenticity, but on the positive side, they seemed to keep the town from being a complete ruin. Bert ordered coffee and a sweet roll for them. The roll was encased in cellophane, and he remarked that it could have been offloaded from a truck months before.

“I’m still thinking about Al and Margie,” Helen said. “I’d guess them to be a couple. Do you think they’re married?”

“Maybe,” Bert said. “Ha, maybe that old nun in the monastery asked them. Seriously, they did seem different from couples who’ve been together so long they echo each other, or look alike. Two unique personalities. Did you notice how he talked mostly about the Camino, and she mostly about people, even her children and grandchildren?”

“Right,” Helen replied. “I wonder how they saw us. If they realized that we’re just friends. Not a couple. I did call you my friend. We said we live in different parts of the country. But my impression was they’re living together in two different places, not living separately like us.”

Bert sipped his coffee and said nothing.

Helen followed suit and sat back to relax. It wasn’t the first time Helen had wondered what people thought about her and Bert. Would she and Bert give the impression of being just friends? Al and Margie gave her the impression of being a couple. That nosy woman in Pamplona had called him her boyfriend, so maybe they came across as a couple. Maybe most people would initially assume them to be a couple. What about Jack and Emma, the Irish couple, trying to make their story a romance when it wasn’t? What did they see that made them think that? Having been just friends for so long, it seemed to her that it ought to be obvious to others they met.

But on the other hand, here as they shared the Camino’s pains and joys, she wondered about the nature of their friendship. That weekend after their divorces, and once in Orebed Lake, real intimacy had seemed like it could be close, but she had pushed it away not wanting to spoil a good thing. She began to guess that any detectable vibrations they gave off might be confused and confusing.

Rested, they started out again. On the way out of El Ganso they walked through a scene created by centuries of deterioration. Mostly abandoned, like Santa Catalina, the village was strewn with roofless buildings. Crumbling rock walls surrounded trees growing up within spaces that were once rooms. Helen slowed to adjust her pack and Bert walked onto the porch of a ramshackle church. Moments later they were walking again.

“What did you see in the church?”

“Oh, the door was locked. Couldn’t see anything. I was trying to translate a note posted on the door. I had to use a lot of guesswork, but from what I could gather, somebody—local people I suppose—seem to be trying to recruit help to restore the church. It seemed to be about raising money.”

“Look like they were having any success?”

“No, it didn’t look encouraging. The notice was dated last December, and it was faded and dog-eared.”

“Too bad.”

“I agree. Maybe that old church has little to recommend it architecturally or artistically, but it must have a place in the history of the town. I imagine at one time it played an important role in the lives of the inhabitants of this burg. Maybe if the church could be restored, the little settlement would have a less mournful feel to it. Another sign of the change that we’ve been talking about.”

Soon a tall, blue sign holding the drawings of a stick pilgrim with a staff in hand, a Camino shell icon, and a yellow arrow pointed them off the little-used paved road and back onto the yellow-brown dirt path. Almost immediately they passed one of the concrete Camino markers. This one sported a rainbow painted on the concrete and a wooden cross on top. People had left stones piled on the top of the monument.

Wildflowers lined the path: bright yellow dandelions on tall wind-blown stems, white daisies that reminded Helen of the omnipresent weeds in Florida called Spanish needles, and other daisies with white petals and bright yellow centers that clung to stone fences.

Then a wire fence appeared alongside the path, separating it from a farm field where white, horned cattle lay in the sun. Hikers, no doubt the type comfortable being called pilgrims thought Helen, had taken sticks and woven them into the wire to form crosses. She was sure neither Bert nor she would emulate them.

Arriving in Rabanal, after climbing most of the four-mile distance, they were pleased that this town was not another ruin. They first visited its newly restored church and then had a soft drink, pastry, and bathroom break at a café-bar. Inquiring at the Albergue Guacelmo for Jack and Emma, they learned the hospitaleros had gone together to Astorga to buy supplies and weren’t expected to return for an hour or more. Helen was not particularly disappointed to be missing them. She did not want a repeat of the story-telling episode.

The walk to Foncebadón continued on a more rugged and steep trail than the ones they had enjoyed in the early morning out of Santa Catalina. But the difficulty of walking was more than compensated for by the abundant, colorful wildflowers along the way. The bright yellow flowers of gorse mingled with the bluer tones of heather and lavender. Helen and Bert each lingered to take many photographs, with the added benefit that slowing their pace made the very steep climbs on much narrowed and stony paths a bit less noticeable to their weary bodies. Bert was placing his sore ankle deliberately and cautiously with each step.

When they finally arrived, Helen immediately observed that Foncebadón offered some unusual contrasts. The town had never been large and, not unlike Santa Catalina and El Ganso, perhaps half its structures were complete ruins. Nevertheless, it sported three albergues, one newly opened, and a more or less upscale-looking restaurant with a thatched roof outbuilding and a sign touting its medieval décor and menu. The cars parked along the new road in front of the restaurant suggested that the town had become a destination for day-trippers. One more surprise was a sign displaying an architect’s rendering of a proposed second new albergue, this apparently a large one. Bert said he doubted that one would be built soon, given the present state of the economy, but the signs of the town’s growth and renewal were impressive nevertheless.

At their albergue, they dropped off their packs, and agreed to begin their afternoon over glasses of beer and bowls of soup. Foncebadón was too intriguing for them to spend much time in their room. They could rest and recover in the restaurant.

“What a magical place this is,” Helen said after their lunch. “I want to get out my camera and stroll around. It’s so picturesque. And, something about the light is strange, alluring.”

For the next hour and a half they enjoyed the scenery, and tried to capture the mood of the place on the memory chips in their cameras. Bert showed Helen his two favorites, saying they might be the best of the whole trip so far. All along the Camino they had passed monuments of one kind or another on which people had placed stones. Often they were waymarks for the Camino, bases of statues and crosses, or foundations of fountains in town squares. They had guessed that people put them there as symbols of devotion.

Here in Foncebadón he had photographed a monument similar to the others. It was a cross on a stonework pedestal. This one was unique in having a sign asking passersby not to place stones on it. Somehow the incongruity appealed to him, he said. If the residents of Foncebadón wanted to be different, they had found at least one small way to do so.

His other favorite was a photo of two dogs sprawled out sleeping in the old road that the Camino followed, unperturbed as passing hikers tiptoed around them. He particularly liked this image, he said, because the popular books about the Camino by actress Shirley MacLaine and Brazilian author Paulo Coelho had both made much of Foncebadón and especially the legends about its fearsome wild dogs.

Later in the afternoon, as agreed, they met Al and Margie at a table on an enclosed porch in front of the albergue. The men ordered beers and the women opted for wine. The innkeeper also brought tapas. They ate them without questioning how long the sardine topped bread slices had been sitting out on the bar without refrigeration, perhaps all day, or since the day before.

Helen surrendered to her curiosity and asked about how they had met. The answer turned out to be far more involved and richer in drama than expected.

“Actually, we met in high school,” said Al. “We were high school sweethearts. It was true love. We were enthralled with each other. We were convinced that we had an enduring love, an indelible bond. We pledged to spend the rest of our lives together and had every expectation of doing so.”

“I was invited to Al’s family’s Thanksgiving dinner. He came to my family’s Christmas. He endured all my obnoxious cousins. I’m still impressed that he was able to do that. Our families were sure we would marry. His family adopted me and mine adopted him.”

“Yeah, we were a couple before we knew what it was all about. On the other hand, I’ll bet we knew more about it than some young people do today.”

“Enter reality,” interjected Margie. “We broke up over some issue that we don’t even remember. New boy- and girlfriends entered the picture. I think we both expected to get back together. But before we knew it, Al was off to college and me to nursing school. The marriage made in heaven was dashed on the rocks of day-to-day happenings.”

“My turn,” said Al. “We married other people, and both of us had decades of happiness with near-perfect spouses. I was blessed with two daughters and two grandchildren. Margie has three children and a handful of grandchildren. Our lives couldn’t have been much closer to perfect. Except for the deaths of our spouses.”

“I was okay for a while,” Margie continued. “My son encouraged me to leave the old place and build a new house next to his. It’s on a pristine and quiet lake. It’s beautiful, I love him, and I love it, but it wasn’t the answer. I was still lonely, not having someone to share the good things life has to offer. And of course to help endure the difficult things. I wanted something different. I’m no longer a young wisp of a woman. But one day it struck me that part of that young woman still remains, and I wanted her to find a home.”

With a brief critical look, Helen noted that Margie had weathered the years really well. Was she really older than Helen? She looked strong, like a woman who enjoys the outdoors. Margie obviously liked hiking, and Helen guessed she might be a golfer or a skier too.

“Maybe we’re still missing some of the facts here,” said Al. “I became a widower at about the same time that Margie lost her husband—four or five years ago. Like her, I adapted well at first and have done all right on the whole. But once I got past the day-to-day and began thinking about the long road ahead, I too realized I was lonely. I can’t tell you what it was like. Well, I probably could, but I don’t want to think about it.”

“Make no mistake, we were sad. Not desperate, but sad,” said Margie. “We have fond memories. But we have many—or at least several—good years left, and we wanted them to be full, productive, rewarding, and fun! We love our children, we honor our past, and we cherish the memories.”

Al chanced another explanation.

“Margie’s newly built house is in the North Country of New York State. I have a nice house in south Florida and a family summer cottage in the Adirondacks. We’re awash in places to live—special places with memories and touchstones—and, separated by more than 1,500 miles. And, of course there are the children and grandchildren to visit and enjoy. We aren’t going to give up all that!

“But then we re-found each other and weren’t going to give up on that either. We had no reason to hunker down in our empty houses because we couldn’t bear to leave them. We decided to find a way to live, and love, and take the bounty offered to us in the afternoon of our lives.”

Love in the afternoon. For Helen it was a more frightening than appealing concept. She found herself wondering what Bert was thinking. She’d almost surely never ask him. It was too close to the place they never went in their conversations.

She was perfectly capable of managing her own afternoons, she thought. She was no more ready to again surrender to the demands of a shared life than she had been at any other time since her divorce. Stability was at stake, and hard-won professional success had granted her a measure of predictability, accomplishment, and serenity. Al and Margie must not value their individual freedoms to go where they wanted and do what they needed to do for themselves as much as she did. So why was she having this conversation with herself?

Margie interrupted her thoughts. “Al left some things out. It’s like a movie plot. We met up again at our high school reunion. I didn’t expect Al to attend, but I suppose I had certain hopes. I was talking to a nice man—someone I also knew from high school—and all of a sudden he asked me if I had seen Al. Well, no, I said. He looked over my shoulder and then I turned around and there was Al.

“We swept toward one another and I thought I heard violins playing. But that must have been a hallucination because after all it was a hockey arena. No musicians were anywhere in sight. Anyway, I don’t want to exaggerate, but we talked and it was as if a forty-year-old loving relationship again instantly rekindled, like we were picking up on and continuing a conversation that was interrupted decades ago.

“It was a strange feeling. On one hand, I felt more comfortable talking with Al than I’d been in years, but I was tense because I didn’t know how he felt. Or, what I would do if he rejected me.”

“She was on the prowl,” Al said teasingly.

“Well, I suppose I was. I didn’t know it then. I was worried about what you were thinking. Now I know that you were on the prowl, too.”

“Yeah, and the chances of me rejecting you were zip.”

The look between them told Helen it had obviously been a grand reconnection; they seemed crazy in love with each other. At their age, the word “crazy” might aptly describe it.

“It sounds like a story of true love,” Helen said, hoping her skepticism wasn’t creeping into her voice. She was happy for them, but couldn’t imagine herself behaving like them. Thinking back on a high school infatuation with basketball player, she knew their story was not in her future. She saw him at the reunion last year. He was still attractive. But, no way, would he fit in her life.

“How is it working? Have you found what you were looking for? Have you been able to manage the complexity?” Helen asked the last crucial question with curiosity and incredulity, but tried to keep her tone light.

“We’re burning a lot of gasoline and wearing out tires and vehicles traipsing across the country,” said Al. “We really can’t imagine it any other way. We follow our hearts. We’re so lucky to have this chance. Challenges we have. But we love each other. Love is quite special when it comes with such a lot of living to sink its roots in.

“We know we’re not perfect,” he went on. “But we also know we’re not the half-baked, forlorn folks we were before that reunion. We both have good jobs and we work hard at them. But there are more than enough spaces in our lives to share with each other.”

Helen wasn’t convinced. This wasn’t just about love. Their talk of honoring the past while plunging headlong into a new relationship didn’t ring true to Helen. She knew from experience, when people plunge heedlessly ahead, they leave others behind. What they were describing just doesn’t work in real life. And how could they possibly be doing all this traveling when they had jobs? Responsibilities to kids and even to work can’t just be thrown to the winds. People get hurt. Love has to accommodate.

Their tale of new soul mates and a dreamy future made her enjoyable, platonic relationship with Bert look almost barren. Helen hid her discomfort with conscious effort. She smiled and wished them well as, to her relief, they left saying they’d decided to have dinner at their hostal.

Not in the least ready to talk about their story, Helen was relieved when Bert didn’t plunge into it either saying only, “That was quite a tale! I know what their nickname will be―the lovebirds.”

They finished their drinks thinking their own thoughts.

“Let’s have a nonpilgrim dinner tonight,” Helen suggested. I’d like to see what that medieval restaurant is like.”

“Good idea.”

They headed off to the restaurant and were able to get seated right away. All the later reservations were booked, but early worked for them.

Their long trestle table had a deep red tablecloth and was lighted by a candelabra dripping long stalactites of melted wax. The terracotta dishes and wine goblets and the waitress’s costume added to the medieval aura of the place, although Helen noted from the cluster of locals near the bar that it also seemed to be the regional hangout.

“What a great meal,” said Bert when they had finished. “A whole platter of meaty ribs and broiled potatoes after so many days of almost-enough trout or chicken, and the omnipresent patatas fritas. I was ready. Twice the calories and no regrets. And, I am enjoying the buzz from beer at lunch, more beer with Al and Margie, and then the wine with our megameal.”

Helen agreed. Foncebadón would be part of the Camino she would not soon forget.

When they had returned to the albergue, no roommates had yet shown up to take the other two bunks. Helen had to ask the lurking question.

“What did you think? I know they seemed happy and I wish them the best, but Al and Margie’s story is hard to accept at face value. I almost wish Jack and Emma—our tale-weaving Irishmen—were here. They’d shed some light on it. I know the lovebirds’ dead spouses can’t feel rejected, but can you imagine after thirty years of happy marriage just blithely, impulsively letting an old high school flame get that close to you, just like that? Can you imagine it?”

“Well, yes and no,” said Bert. “I think Jack and Emma would take them at their word.”

“But they’re making themselves so vulnerable,” Helen interrupted. “What if the glow fades on either side? How big will that pain be, for heaven’s sake?”

“I don’t want to see it that way. I think I always sort of expected the stars would someday offer me something like their story,” Bert mused. “I don’t feel like I’m lonely, but maybe I am. Maybe that’s why I agreed to come on the Camino.”

“Well, it felt to me like they’d reverted to a childhood fantasy of what love is,” Helen said. “They said they were happy, and I didn’t believe it.”

“Give them some space, Helen. I don’t know why you see disaster coming toward them. It is so unlike you to be the pessimist. I’m the one who’s been a failure at love. My ex told me often enough that I didn’t measure up as a husband. But I’m willing to learn. With these lovebirds I felt like what you see is what you get. The real thing. As if life were new again.

“Oh shit! Maybe we need another pitcher of wine, dear lady. And if you’ll agree not to jump to any more snarky conclusions, I’ll agree not to overreact.

“Or, maybe I can’t stop myself from overreacting. Honestly, Helen, why be so negative? Why can’t they be just what they seem to be? Why can’t what they have be possible? Such skepticism from your virginal heights could be impetus enough for me to seek the nearest train or bus back to the Madrid airport.” Looking away, he wiped his brow.

He turned back toward her, took a quick breath, and explained that he hadn’t meant to say anything like that, and it was probably all the beer and wine doing the talking.

“Actually, Al and Margie’s story brought a loneliness into focus that I didn’t know was in me, and I have begun to think that I’m less happy than I used to believe.” He gave a half smile and she thought it was not with joy but maybe a recognition of the loneliness.

She had no response. She was overwhelmed. They sank into their bunks and she didn’t look at him. No one else had arrived to claim the room’s vacant upper bunks. Before she drifted off with Bert’s words ringing in her ears, it struck her that maybe what really bothered her about the day’s conversation was an inexplicable feeling that she was being left behind.

Whether it was a wine-induced stupor or a deep sleep, when she was awakened by an alarm at six on the following morning, she was surprised that roommates had arrived during the night—Americans, in fact. They were college students separated from their group because their colleagues had filled the albergue where they had intended to stay. Either the two girls had been extraordinarily quiet or Helen had been completely out of it, because she hadn’t heard a sound. They apologized for waking her.

Bert was already up when their alarm went off. He had left the room, and she figured he must be waiting in line for an available shower stall. She wondered if he also had a slight headache.

When her head cleared they needed to have a talk, although she couldn’t begin to think of what words she would use. Camino magic might be necessary. If none appeared today, maybe by the time they got to Santiago she’d know what to say.

Walking out of Santa Catalina de Somoza, they passed through what for the most part is a ghost town. Perhaps half of the thirty or forty stone dwellings were complete ruins, and of those that were maintained or restored, few seemed to be permanently occupied. Helen noted that the restored houses seemed to all sport bright colored front doors, blue or green being the most popular, and had door knockers shaped like fists.

The two albergues appeared to be the only going concerns in the little settlement. The guidebook said that the place had a population of fifty, but Helen doubted the total could be close to that many.

The two-lane road was paved with bricks to the edge of town. Crumbling stone fences and walls lined it. Little white and pink flowers pushed through the rubble and climbed over the stones.

“Rock garden flowers,” Bert noted.

Where a door or window used to be, Helen sometimes could look through into a grassy space that used to be a room and see a big white multiflora rose bush or two. She had Bert take her picture in a former doorway where the lintel was so low she had to duck to stand in the space.

“I read that somoza in Latin meant ‘under the mountain.’ I can’t find it in my Spanish dictionary. But we’re sure surrounded by mountains,” Bert said as they left the paved road and started along a yellow dirt path.

Mountains were on every horizon except behind them, and they were continuing the gradual climb they’d experienced all day yesterday. On the walk to Santa Catalina, Helen had been fascinated that Astorga and the spires of its cathedral had remained visible behind them for most of the seven miles.

The path was straight, level, and well-maintained. Surprisingly, on one side it paralleled the paved and little used secondary road they had just left, and on the other side a gravel farm road. On most sections of the Camino they would have found themselves walking on one or other of these, and having a surface they did not need to share with cars and trucks or with farm tractors seemed an unlikely luxury—especially here where the parallel roads were practically unused. Concrete posts about three feet high with the Camino shell icon and sometimes also a yellow arrow on them marked the path. Where there were fields between the path and the paralleling roads, they often were outlined by stone fences.

Few other walkers were in sight, and most of the time Helen felt that the two of them were quite alone. Strange, she thought; I spend most of my life alone, but this feeling that Bert and I are the only people in the world is new, and different. I wonder if he has noticed it.

Her rare moment of sensing a shared solitude changed when they came across a couple sitting by the trail, enjoying a snack. He was perched on the stone fence and she sat on the ground with her back against one of the Camino markers.

“Come join us,” the blue-eyed woman said, smiling softly and broadly under a visor and holding out a plastic bag. “Look, we picked up some goodies in Astorga.”

From their accent, or lack thereof, Helen knew that they were surely North Americans—probably Canadians, she guessed.

Their times with the few Americans they had met on the trail so far, like Gwen and her husband Daryl, were particularly memorable. Helen thought that perhaps it was because of common experiences; if one mentioned a high school reunion, for example, the other would have some idea of its meaning, whereas it would likely draw a blank stare from a German or Spaniard. Of course, they hadn’t crossed the Atlantic Ocean to talk with other Americans, but their very rarity on the Camino increased the allure of occasionally meeting up with them.

"Thanks. What have you got? And where do you hail from?” Helen said when they reached the other couple.

“Have an apple. Oh, we’re from . . . You know, that’s a difficult question. We have houses in two different states. Uh, I hadn’t thought about it, but as things stand, neither can be described as our primary residence. I’ll spare you all the details. Let’s just say Florida, and leave it at that.”

“Well, we have that in common. Same answer from us. I’m Helen and I live in a small town on the Florida Gulf Coast. My friend Bert lives in one of the ‘burbs’ near Washington, D.C.”

Having thus broken the ice, they soon learned that the tanned, dark-haired, and somewhat more reticent Al and the fair-skinned, trim, and outgoing Margie were affable and easy companions. A few years their senior, they seemed to exude energy and good health, making Helen wonder whether they were like that all the time, or were just buoyed by being on the Camino.

Each finding a flat stone on the fence, Bert and Helen sat down with them, offering some of their dried apricots for the shared mini-picnic. The banter was mostly superficial. Where did you start? How long have you been walking? How did you learn about the Camino? Where are you headed tonight?

They were all going to Foncebadón, although they had set their sights on different hostals. Margie had booked them a private room, while Helen had accepted the last two spaces in the albergue she called, and they would be in a room for four. Bert proposed, and all agreed, that they would meet again when they reached their destination and would have a beer and maybe a pilgrim dinner together. Their new acquaintances resumed walking, while Bert and Helen rested a while longer.

A bit later the path joined one of the roads and brought them into the village of El Ganso, another abandoned looking town of crumbling stone fences and houses. Here they came upon the landmark Mesón Cowboy—the Cowboy Bar. Helen thought that the incongruous bar and its equally quaint neighboring café might spoil the mood for those who value authenticity, but on the positive side, they seemed to keep the town from being a complete ruin. Bert ordered coffee and a sweet roll for them. The roll was encased in cellophane, and he remarked that it could have been offloaded from a truck months before.

“I’m still thinking about Al and Margie,” Helen said. “I’d guess them to be a couple. Do you think they’re married?”

“Maybe,” Bert said. “Ha, maybe that old nun in the monastery asked them. Seriously, they did seem different from couples who’ve been together so long they echo each other, or look alike. Two unique personalities. Did you notice how he talked mostly about the Camino, and she mostly about people, even her children and grandchildren?”

“Right,” Helen replied. “I wonder how they saw us. If they realized that we’re just friends. Not a couple. I did call you my friend. We said we live in different parts of the country. But my impression was they’re living together in two different places, not living separately like us.”

Bert sipped his coffee and said nothing.

Helen followed suit and sat back to relax. It wasn’t the first time Helen had wondered what people thought about her and Bert. Would she and Bert give the impression of being just friends? Al and Margie gave her the impression of being a couple. That nosy woman in Pamplona had called him her boyfriend, so maybe they came across as a couple. Maybe most people would initially assume them to be a couple. What about Jack and Emma, the Irish couple, trying to make their story a romance when it wasn’t? What did they see that made them think that? Having been just friends for so long, it seemed to her that it ought to be obvious to others they met.

But on the other hand, here as they shared the Camino’s pains and joys, she wondered about the nature of their friendship. That weekend after their divorces, and once in Orebed Lake, real intimacy had seemed like it could be close, but she had pushed it away not wanting to spoil a good thing. She began to guess that any detectable vibrations they gave off might be confused and confusing.

Rested, they started out again. On the way out of El Ganso they walked through a scene created by centuries of deterioration. Mostly abandoned, like Santa Catalina, the village was strewn with roofless buildings. Crumbling rock walls surrounded trees growing up within spaces that were once rooms. Helen slowed to adjust her pack and Bert walked onto the porch of a ramshackle church. Moments later they were walking again.

“What did you see in the church?”

“Oh, the door was locked. Couldn’t see anything. I was trying to translate a note posted on the door. I had to use a lot of guesswork, but from what I could gather, somebody—local people I suppose—seem to be trying to recruit help to restore the church. It seemed to be about raising money.”

“Look like they were having any success?”

“No, it didn’t look encouraging. The notice was dated last December, and it was faded and dog-eared.”

“Too bad.”

“I agree. Maybe that old church has little to recommend it architecturally or artistically, but it must have a place in the history of the town. I imagine at one time it played an important role in the lives of the inhabitants of this burg. Maybe if the church could be restored, the little settlement would have a less mournful feel to it. Another sign of the change that we’ve been talking about.”

Soon a tall, blue sign holding the drawings of a stick pilgrim with a staff in hand, a Camino shell icon, and a yellow arrow pointed them off the little-used paved road and back onto the yellow-brown dirt path. Almost immediately they passed one of the concrete Camino markers. This one sported a rainbow painted on the concrete and a wooden cross on top. People had left stones piled on the top of the monument.

Wildflowers lined the path: bright yellow dandelions on tall wind-blown stems, white daisies that reminded Helen of the omnipresent weeds in Florida called Spanish needles, and other daisies with white petals and bright yellow centers that clung to stone fences.

Then a wire fence appeared alongside the path, separating it from a farm field where white, horned cattle lay in the sun. Hikers, no doubt the type comfortable being called pilgrims thought Helen, had taken sticks and woven them into the wire to form crosses. She was sure neither Bert nor she would emulate them.

Arriving in Rabanal, after climbing most of the four-mile distance, they were pleased that this town was not another ruin. They first visited its newly restored church and then had a soft drink, pastry, and bathroom break at a café-bar. Inquiring at the Albergue Guacelmo for Jack and Emma, they learned the hospitaleros had gone together to Astorga to buy supplies and weren’t expected to return for an hour or more. Helen was not particularly disappointed to be missing them. She did not want a repeat of the story-telling episode.

The walk to Foncebadón continued on a more rugged and steep trail than the ones they had enjoyed in the early morning out of Santa Catalina. But the difficulty of walking was more than compensated for by the abundant, colorful wildflowers along the way. The bright yellow flowers of gorse mingled with the bluer tones of heather and lavender. Helen and Bert each lingered to take many photographs, with the added benefit that slowing their pace made the very steep climbs on much narrowed and stony paths a bit less noticeable to their weary bodies. Bert was placing his sore ankle deliberately and cautiously with each step.

When they finally arrived, Helen immediately observed that Foncebadón offered some unusual contrasts. The town had never been large and, not unlike Santa Catalina and El Ganso, perhaps half its structures were complete ruins. Nevertheless, it sported three albergues, one newly opened, and a more or less upscale-looking restaurant with a thatched roof outbuilding and a sign touting its medieval décor and menu. The cars parked along the new road in front of the restaurant suggested that the town had become a destination for day-trippers. One more surprise was a sign displaying an architect’s rendering of a proposed second new albergue, this apparently a large one. Bert said he doubted that one would be built soon, given the present state of the economy, but the signs of the town’s growth and renewal were impressive nevertheless.

At their albergue, they dropped off their packs, and agreed to begin their afternoon over glasses of beer and bowls of soup. Foncebadón was too intriguing for them to spend much time in their room. They could rest and recover in the restaurant.

“What a magical place this is,” Helen said after their lunch. “I want to get out my camera and stroll around. It’s so picturesque. And, something about the light is strange, alluring.”

For the next hour and a half they enjoyed the scenery, and tried to capture the mood of the place on the memory chips in their cameras. Bert showed Helen his two favorites, saying they might be the best of the whole trip so far. All along the Camino they had passed monuments of one kind or another on which people had placed stones. Often they were waymarks for the Camino, bases of statues and crosses, or foundations of fountains in town squares. They had guessed that people put them there as symbols of devotion.

Here in Foncebadón he had photographed a monument similar to the others. It was a cross on a stonework pedestal. This one was unique in having a sign asking passersby not to place stones on it. Somehow the incongruity appealed to him, he said. If the residents of Foncebadón wanted to be different, they had found at least one small way to do so.

His other favorite was a photo of two dogs sprawled out sleeping in the old road that the Camino followed, unperturbed as passing hikers tiptoed around them. He particularly liked this image, he said, because the popular books about the Camino by actress Shirley MacLaine and Brazilian author Paulo Coelho had both made much of Foncebadón and especially the legends about its fearsome wild dogs.

Later in the afternoon, as agreed, they met Al and Margie at a table on an enclosed porch in front of the albergue. The men ordered beers and the women opted for wine. The innkeeper also brought tapas. They ate them without questioning how long the sardine topped bread slices had been sitting out on the bar without refrigeration, perhaps all day, or since the day before.

Helen surrendered to her curiosity and asked about how they had met. The answer turned out to be far more involved and richer in drama than expected.

“Actually, we met in high school,” said Al. “We were high school sweethearts. It was true love. We were enthralled with each other. We were convinced that we had an enduring love, an indelible bond. We pledged to spend the rest of our lives together and had every expectation of doing so.”

“I was invited to Al’s family’s Thanksgiving dinner. He came to my family’s Christmas. He endured all my obnoxious cousins. I’m still impressed that he was able to do that. Our families were sure we would marry. His family adopted me and mine adopted him.”

“Yeah, we were a couple before we knew what it was all about. On the other hand, I’ll bet we knew more about it than some young people do today.”

“Enter reality,” interjected Margie. “We broke up over some issue that we don’t even remember. New boy- and girlfriends entered the picture. I think we both expected to get back together. But before we knew it, Al was off to college and me to nursing school. The marriage made in heaven was dashed on the rocks of day-to-day happenings.”

“My turn,” said Al. “We married other people, and both of us had decades of happiness with near-perfect spouses. I was blessed with two daughters and two grandchildren. Margie has three children and a handful of grandchildren. Our lives couldn’t have been much closer to perfect. Except for the deaths of our spouses.”

“I was okay for a while,” Margie continued. “My son encouraged me to leave the old place and build a new house next to his. It’s on a pristine and quiet lake. It’s beautiful, I love him, and I love it, but it wasn’t the answer. I was still lonely, not having someone to share the good things life has to offer. And of course to help endure the difficult things. I wanted something different. I’m no longer a young wisp of a woman. But one day it struck me that part of that young woman still remains, and I wanted her to find a home.”

With a brief critical look, Helen noted that Margie had weathered the years really well. Was she really older than Helen? She looked strong, like a woman who enjoys the outdoors. Margie obviously liked hiking, and Helen guessed she might be a golfer or a skier too.

“Maybe we’re still missing some of the facts here,” said Al. “I became a widower at about the same time that Margie lost her husband—four or five years ago. Like her, I adapted well at first and have done all right on the whole. But once I got past the day-to-day and began thinking about the long road ahead, I too realized I was lonely. I can’t tell you what it was like. Well, I probably could, but I don’t want to think about it.”

“Make no mistake, we were sad. Not desperate, but sad,” said Margie. “We have fond memories. But we have many—or at least several—good years left, and we wanted them to be full, productive, rewarding, and fun! We love our children, we honor our past, and we cherish the memories.”

Al chanced another explanation.

“Margie’s newly built house is in the North Country of New York State. I have a nice house in south Florida and a family summer cottage in the Adirondacks. We’re awash in places to live—special places with memories and touchstones—and, separated by more than 1,500 miles. And, of course there are the children and grandchildren to visit and enjoy. We aren’t going to give up all that!

“But then we re-found each other and weren’t going to give up on that either. We had no reason to hunker down in our empty houses because we couldn’t bear to leave them. We decided to find a way to live, and love, and take the bounty offered to us in the afternoon of our lives.”

Love in the afternoon. For Helen it was a more frightening than appealing concept. She found herself wondering what Bert was thinking. She’d almost surely never ask him. It was too close to the place they never went in their conversations.

She was perfectly capable of managing her own afternoons, she thought. She was no more ready to again surrender to the demands of a shared life than she had been at any other time since her divorce. Stability was at stake, and hard-won professional success had granted her a measure of predictability, accomplishment, and serenity. Al and Margie must not value their individual freedoms to go where they wanted and do what they needed to do for themselves as much as she did. So why was she having this conversation with herself?

Margie interrupted her thoughts. “Al left some things out. It’s like a movie plot. We met up again at our high school reunion. I didn’t expect Al to attend, but I suppose I had certain hopes. I was talking to a nice man—someone I also knew from high school—and all of a sudden he asked me if I had seen Al. Well, no, I said. He looked over my shoulder and then I turned around and there was Al.

“We swept toward one another and I thought I heard violins playing. But that must have been a hallucination because after all it was a hockey arena. No musicians were anywhere in sight. Anyway, I don’t want to exaggerate, but we talked and it was as if a forty-year-old loving relationship again instantly rekindled, like we were picking up on and continuing a conversation that was interrupted decades ago.

“It was a strange feeling. On one hand, I felt more comfortable talking with Al than I’d been in years, but I was tense because I didn’t know how he felt. Or, what I would do if he rejected me.”

“She was on the prowl,” Al said teasingly.

“Well, I suppose I was. I didn’t know it then. I was worried about what you were thinking. Now I know that you were on the prowl, too.”

“Yeah, and the chances of me rejecting you were zip.”

The look between them told Helen it had obviously been a grand reconnection; they seemed crazy in love with each other. At their age, the word “crazy” might aptly describe it.

“It sounds like a story of true love,” Helen said, hoping her skepticism wasn’t creeping into her voice. She was happy for them, but couldn’t imagine herself behaving like them. Thinking back on a high school infatuation with basketball player, she knew their story was not in her future. She saw him at the reunion last year. He was still attractive. But, no way, would he fit in her life.

“How is it working? Have you found what you were looking for? Have you been able to manage the complexity?” Helen asked the last crucial question with curiosity and incredulity, but tried to keep her tone light.

“We’re burning a lot of gasoline and wearing out tires and vehicles traipsing across the country,” said Al. “We really can’t imagine it any other way. We follow our hearts. We’re so lucky to have this chance. Challenges we have. But we love each other. Love is quite special when it comes with such a lot of living to sink its roots in.

“We know we’re not perfect,” he went on. “But we also know we’re not the half-baked, forlorn folks we were before that reunion. We both have good jobs and we work hard at them. But there are more than enough spaces in our lives to share with each other.”

Helen wasn’t convinced. This wasn’t just about love. Their talk of honoring the past while plunging headlong into a new relationship didn’t ring true to Helen. She knew from experience, when people plunge heedlessly ahead, they leave others behind. What they were describing just doesn’t work in real life. And how could they possibly be doing all this traveling when they had jobs? Responsibilities to kids and even to work can’t just be thrown to the winds. People get hurt. Love has to accommodate.

Their tale of new soul mates and a dreamy future made her enjoyable, platonic relationship with Bert look almost barren. Helen hid her discomfort with conscious effort. She smiled and wished them well as, to her relief, they left saying they’d decided to have dinner at their hostal.

Not in the least ready to talk about their story, Helen was relieved when Bert didn’t plunge into it either saying only, “That was quite a tale! I know what their nickname will be―the lovebirds.”

They finished their drinks thinking their own thoughts.

“Let’s have a nonpilgrim dinner tonight,” Helen suggested. I’d like to see what that medieval restaurant is like.”

“Good idea.”

They headed off to the restaurant and were able to get seated right away. All the later reservations were booked, but early worked for them.

Their long trestle table had a deep red tablecloth and was lighted by a candelabra dripping long stalactites of melted wax. The terracotta dishes and wine goblets and the waitress’s costume added to the medieval aura of the place, although Helen noted from the cluster of locals near the bar that it also seemed to be the regional hangout.

“What a great meal,” said Bert when they had finished. “A whole platter of meaty ribs and broiled potatoes after so many days of almost-enough trout or chicken, and the omnipresent patatas fritas. I was ready. Twice the calories and no regrets. And, I am enjoying the buzz from beer at lunch, more beer with Al and Margie, and then the wine with our megameal.”

Helen agreed. Foncebadón would be part of the Camino she would not soon forget.

When they had returned to the albergue, no roommates had yet shown up to take the other two bunks. Helen had to ask the lurking question.

“What did you think? I know they seemed happy and I wish them the best, but Al and Margie’s story is hard to accept at face value. I almost wish Jack and Emma—our tale-weaving Irishmen—were here. They’d shed some light on it. I know the lovebirds’ dead spouses can’t feel rejected, but can you imagine after thirty years of happy marriage just blithely, impulsively letting an old high school flame get that close to you, just like that? Can you imagine it?”

“Well, yes and no,” said Bert. “I think Jack and Emma would take them at their word.”

“But they’re making themselves so vulnerable,” Helen interrupted. “What if the glow fades on either side? How big will that pain be, for heaven’s sake?”

“I don’t want to see it that way. I think I always sort of expected the stars would someday offer me something like their story,” Bert mused. “I don’t feel like I’m lonely, but maybe I am. Maybe that’s why I agreed to come on the Camino.”

“Well, it felt to me like they’d reverted to a childhood fantasy of what love is,” Helen said. “They said they were happy, and I didn’t believe it.”

“Give them some space, Helen. I don’t know why you see disaster coming toward them. It is so unlike you to be the pessimist. I’m the one who’s been a failure at love. My ex told me often enough that I didn’t measure up as a husband. But I’m willing to learn. With these lovebirds I felt like what you see is what you get. The real thing. As if life were new again.

“Oh shit! Maybe we need another pitcher of wine, dear lady. And if you’ll agree not to jump to any more snarky conclusions, I’ll agree not to overreact.

“Or, maybe I can’t stop myself from overreacting. Honestly, Helen, why be so negative? Why can’t they be just what they seem to be? Why can’t what they have be possible? Such skepticism from your virginal heights could be impetus enough for me to seek the nearest train or bus back to the Madrid airport.” Looking away, he wiped his brow.

He turned back toward her, took a quick breath, and explained that he hadn’t meant to say anything like that, and it was probably all the beer and wine doing the talking.

“Actually, Al and Margie’s story brought a loneliness into focus that I didn’t know was in me, and I have begun to think that I’m less happy than I used to believe.” He gave a half smile and she thought it was not with joy but maybe a recognition of the loneliness.

She had no response. She was overwhelmed. They sank into their bunks and she didn’t look at him. No one else had arrived to claim the room’s vacant upper bunks. Before she drifted off with Bert’s words ringing in her ears, it struck her that maybe what really bothered her about the day’s conversation was an inexplicable feeling that she was being left behind.

Whether it was a wine-induced stupor or a deep sleep, when she was awakened by an alarm at six on the following morning, she was surprised that roommates had arrived during the night—Americans, in fact. They were college students separated from their group because their colleagues had filled the albergue where they had intended to stay. Either the two girls had been extraordinarily quiet or Helen had been completely out of it, because she hadn’t heard a sound. They apologized for waking her.

Bert was already up when their alarm went off. He had left the room, and she figured he must be waiting in line for an available shower stall. She wondered if he also had a slight headache.

When her head cleared they needed to have a talk, although she couldn’t begin to think of what words she would use. Camino magic might be necessary. If none appeared today, maybe by the time they got to Santiago she’d know what to say.

La Cruz de Ferro

Foncebadon to Molinaseca

Wednesday, June 15

Bert was waiting for her on the albergue’s porch. Breaking out of what had become a pattern, they had decided to have coffee and a bite to eat before setting out. They stopped at one of the other albergues—the one with goats running freely about. It had intrigued her the day before. She said it looked as if it were run by either “wanna-be” or “useta-be” hippies.

Not wanting to revisit last night’s conversation just yet, she talked about the day’s destination. They had been planning to stop in the intermediate village of Acebo to keep their distances shorter, but she suggested instead that they go all the way into Molinaseca, assuming Bert’s ankle didn’t bother him too much.

Maybe Bert had forgotten the exchange of the night before, she thought, because he didn’t bring it up either.

As they walked away from the albergue into the cool mountain morning, Helen looked forward to reaching the Cruz de Ferro, the famous iron cross. She was fascinated by the quality of the light. It turned her attention from the ghosts of Bert’s evening words. Had he really said “snarky comments,” and “virginal heights”? He must have been really upset. She was happy for the morning light. It calmed her.

The sun was low in the east behind them, casting their shadows doubly long. Where the sun didn’t touch the land directly, the trail, and stone walls along it all rested in twilight, fading into one another and indistinguishable. Where the sun touched, features glowed with a color that lacked the full range of the light spectrum. The yellows, reds, and oranges burst forth. The greens, blues, indigos, and violets hid.

“I don’t remember ever seeing light like this before,” said Bert.

“You’re reading my mind,” she said. “Hard to believe this is natural.”

“It can’t just be the time of day,” Bert said. “I’ve seen a lot of sunrises, and never one that cast the world in gold like this. Yesterday afternoon’s light had a strange quality, too. Perhaps it’s the combination of temperature, humidity, the season, and the mountain air.”

“But it must be really unusual. The guidebook doesn’t mention it,” Helen said. “I think we’ve lucked into a meteorological special event. Maybe, it’s an omen meaning we have a notable day ahead.”

"Well, it is the day you promised me way back in the Pyrenees," Bert said. "Finally, we get to the Cruz de Ferro and the Camino's highest point. All downhill from today, right."

"Not likely," Helen replied. "Spain seems to keep growing hills and mountains everywhere."

Their progress was pleasurably slow as they played with the light and their cameras. She hoped some of the photos would be beautiful, but doubted they would begin to capture the totality of what her eyes saw.

“How can it be so spectacular and so hard to capture digitally?” asked Helen. She was trying to catch the edge between the light and dark. It wasn’t working.

Bert was looking in the other direction, his camera pointed at the field running up to the trail from the valley below. He said something about it reminded him of burnished gold. “Not even close to what my eyes see,” he complained, squinting at the image on the camera’s small screen.

They agreed to give themselves all the time they wanted, saying this surely would not happen again, and they had a choice of how far to go today anyway. Eventually they fell into a more normal walking pace and the sun rose high enough to pull the rest of the spectrum out of its sleepy start to the day. The gold filled in with blues, greens, indigos, and violets and a new field of amazing beauty greeted them.

Now they were surrounded by thigh-high heather, shoulder-high gorse, and knee-high lavender. The gold glow gave way to air that was blooming purple and lavender, with bright yellow highlights.

“I think the picture I just took of you walking ahead of me at that bend in the trail, with heather above you on the high side of the trail, gorse below, and snow-capped mountains in the distance, is going to be my screensaver for the next year,” Bert called to her.

“I can’t imagine anything much prettier,” she replied. “Of course, it would be quite ordinary without me in the picture.” She tried hard to push the “virginal heights” comment out of her mind and sound normal.

“Look at that snow. Did you expect we would see snow-capped mountains?” she asked. “I hope we don’t have to cross any. But they sure dress up my pictures. I think I took one from the spot where you captured my back. It looks great on the small screen—the heather sweeping far down into that valley and then back up toward the snow. Wow!”

Helen was reasonably sure they wouldn’t be crossing through snow, since this was the highest point on the entire Camino. Over their café con leche yesterday in Rabanal—it seemed like a lot longer ago given the events later in the day—they learned of a tradition. A couple of Austrians told them about it. Since medieval times pilgrims have been bringing a rock from home and carrying it all the way to the Cruz de Ferro. It represents their troubles, illnesses, or burdens. They leave it at the cross, symbolically unburdening their lives for the walk on to Santiago.

“Too bad we didn’t know about that one a month ago,” Bert had said. “I would have picked up a rock outside the doctor’s office, piled my heart problems and the dark hole of the rest of my life on it, left it at the Cruz de Ferro, and been able to go home early.”

“I can’t think of any real burdens to leave behind,” she had replied. “There must be something. I suppose I could have brought a tiny stone along. Maybe I could have brought one for someone else whose life has more pain than mine,” she offered.

They had each picked up a small stone after they heard the story. It was Helen’s idea. Bert had a skeptical look, but had gone along with her.

“The traditions are part of the experience,” she said, “so why not? One should honor traditions. And we saved carrying the extra ounces all this way. If the magic would have worked carrying it from Roncesvalles, why shouldn’t it work if we carry it from here?”

“Good thinking,” said Bert.

Surrounded by pines, the trail flattened and in the distance they saw a clearing. Before them a large mound of stones in a park-like setting spouted a tall wooden pole topped by a small cross. On a ridge in the distance was a line of wind turbines. She at first thought the turbines spoiled the vista, but on second thought decided they seemed to enhance it by emphasizing the sweep of centuries the place had witnessed. People, with and without backpacks, sat at the dozen or so picnic tables in the grassy park surrounding the mound. The trail approached from the east, along a road that led away from the summit. On the south side of the road was a small parking lot.

“Look at all the cars. This appears to be a tourist attraction as well as a highlight of the Camino,” Bert observed.

The mound, probably having been built up over the centuries, was high and steep, and formed of loose stones. Ribbons, flags, and other colorful little pieces of cloth with meanings known only to the donors were attached to the pole as high as one could reach. Maybe each had carried a burden left to flutter off in the breeze.

They waited among a dozen or so hikers for their turns to climb up to the cross. When a couple got up from a bench in the park area on the north side of the mound, they slid into their places to rest and soak in the surroundings for a few more minutes.

Helen noticed a young hiker come up the path from Foncebadón. He seemed to be walking alone. She noticed his attire and gear looked serviceable enough, but were clearly old and well-worn. He slipped out of his backpack and fished in its outside pocket for his rock. A few minutes later she saw a gray-haired man arrive. Tired looking, and slightly stooped, he too seemed to be a lone walker. He set his pack next to the young man’s, against the fence separating the trail from the place where Bert and Helen sat. Helen felt Bert following her eyes to the two men. The older hiker’s rock was already in hand and he took out a camera from his pocket.

He sighed, or maybe just breathed deeply from the morning’s beautiful, but far from easy, climb. He caught the younger man’s attention, apparently asking him to take his picture as he positioned his rock. They smiled and exchanged cameras so each would have his memento.

The older man walked carefully up to the pole. He held his hand on it for a long time. Helen thought he looked like he was taking warmth from the wood. The young hiker took his picture as he stood there. Then the man kissed his rock and placed it gently on the pile. Ready for the action, the young man clicked the camera twice, seeming to catch both moments.

When the older hiker came back down close enough for them to see him well, tears were rolling steadily from his dark eyes down his cheeks. His shoulders were low, his chin down. He reached out for his camera. The second man handed it to him, without looking directly at him. The young man didn’t start immediately up the hill. The two stood side by side, looking back at the cross, not really in each other’s space. Then the younger man, eyes ahead, put an arm around the other’s shoulder. Neither said anything as far as Helen could tell. She wondered whether Bert was equally caught up in the scene.

After a moment, the older man straightened a bit and got out the young man’s camera. The young hiker headed up the mound. Bert and Helen looked at each other. Could he see the tear that burned in her eye?

Helen wondered if the older man had lost his wife, or a child, someone really dear to him. She imagined that he had carried the heavy burden long enough.

It required some effort for Helen to climb up, place her hand on the pole for a minute, and position the rock she added to the pile. She decided to let last night’s conversation cling to the little stone. She felt the stone’s weight in her palm before she set it down; she could almost imagine what leaving it would feel like if she had brought a big burden all the way from home.

Bert remained below and took her picture. The wind was blowing gently and she felt calm standing up there all alone. He shouted up for her to pose, and took another photo of her smiling holding the pole with one hand, the other outstretched, open-armed, embracing the moment. She scrambled down, giving her spot to Bert.

She caught a nice photo of him looking up the pole to the cross atop it, or maybe at the fluttering pieces of cloth. Then another as he added his stone to the pile. He straightened and she was ready to snap another picture, but he stood a few moments with his back to her. She wondered what he was doing. Then he turned and scrambled back down, seeming somber, with no smile at all. That was not how she had felt coming back down from the mound.

“What were you doing up there? What’s up?” said Helen, when he was back on the ground.

“Oh, it was just that . . . something that looked like a wallet caught my eye. But it was something else. It’s hard to explain . . . really hard. We can talk about it later . . . maybe by the time we get to Santiago. I’m ready to get walking again now.”

They slipped into their packs and started down the broad path toward Acebo.

“That was a moment I won’t soon forget,” said Helen.

“I had the same thought,” Bert said.

They walked on in silence.

The path became a wide clay one with landscape timbers edging it, the kind of smooth, level, robust path the National Park Service builds where many tourists will walk between sights. Sure enough, in a half mile or so they came to a second parking area.

“You were right, Bert. This is also an attraction for motorized tourists,” she commented. Just after the parking area, it narrowed back to a hiking path. Bert seemed lost in his own thoughts. They started down a steeper descent. They each lengthened their walking poles.

Helen’s thoughts slipped back to the scene of the two pilgrims at the cross. She found she was okay with thinking of them as “pilgrims” even though she couldn’t possibly think of herself that way. She had sensed pure empathy, with no return implied. She could picture herself as the comforter. At least she thought she could. It was a role that came naturally to her. Nevertheless, she harbored a faint doubt that she could connect the way the young man had, so fully without intrusion.

She didn’t want to think about it, or about the lovebird conversation with Bert. On to simpler things, like not stumbling on this path. The vista was spectacular. Green and blue snow-capped mountains surrounded them. They walked near the road initially but soon the path went cross country. Presumably it was shorter than following the gradual decline of the road around hairpin turns and terraced straightaways. But unlike the road, the trail was steep and stony.

“Bert, how’s your ankle doing with this?”

“I‘m taking pains—pun intended—to place my foot flat and firm,” he said. “It’s a challenge. I think I don’t have as good balance walking step by step as I would with a more spontaneous stride. It’s like riding a bicycle; as long as you’re moving you are stable, but when you hesitate you fall over.”

Not wanting to distract him further, she let herself slide back into her thoughts about the men at the cross. A strange thought popped up. What if instead of being the comforter, she found herself in the position of that man who needed comfort? Would she be willing to accept it, or would she pull away? She hated to be needy and couldn’t picture herself in the role of “comforted,” even comfort as genuinely and unobtrusively offered as by the young hiker.

The trail took another turn toward the difficult. She saw the road meandering to the left below them and wondered if they ought to be walking along it instead of this steep, rocky trail. Her sore toes, bumping into the ends of her boots, were difficult to ignore. She adjusted her walking sticks again making them longer still for the sharp downhill ahead. Her conscious brain was fully engaged in the walking.

The day had in no way become less spectacular. The sun was still with them, warming their backs. The pinkish heather that was on both sides of the trail when they started down had thinned. The bright yellow gorse and deep blue lavender had taken over the color scheme, everywhere joined by tall white and low yellow flowers she couldn’t identify. The sky was big. She could see in every direction. The Camino’s beauty filled her senses and expanded her spirit. Her heart was going to strange, never-visited places, although not yet to last night’s words with Bert.

The pilgrim’s tears had pulled her into thinking about how the Camino had called out to her when she first learned about it. It wasn’t out of sadness, like him. She was at the top, and life was good. She had done what she hoped to do in her career.

She felt good about how far she had come and how she had gotten there. She had her success at the refuge. She had her sisters who she cared about, albeit from a distance. It surprised her, but she enjoyed their interest in her adventure.

And then, despite last night’s comments, there was good friend Bert. She wondered what he’d seen up on the Cruz de Ferro. It must have been why he seemed almost sad when he came down. She had felt so joyous up there. Was she really here on the Camino in celebration, like she’d thought? What was it about last night’s exchange with Bert and today's events that was letting these contrary thoughts seep in?

She’d been in love like Al and Margie once upon a time. They met in graduate school. It was good to meet someone who didn’t know her family. Someone who didn’t know she’d always been the extra kid, the one that came ready-made, not quite one of them, always needing to be good so they’d want her. She and Greg would start fresh. Neither had to accept ready-made roles. Not having children right away seemed natural and agreeable. Just two of them seemed perfect.

But it was a mistake to put so much faith in someone. Maybe he really did love her, but obviously not enough. Within months of when the Fish and Wildlife Service asked her to take an appointment in Alaska, they had filed for divorce. He had no interest in leaving the business he’d built. He hadn’t even asked her to stay, so why consider limiting her career? She wasn't quite good enough to make him want her forever.

Helen made sure they parted friends. Finding herself alone was nothing like the experience Al and Margie had described. She didn’t want or need Greg in her life. She’d gotten along just fine. Maybe that’s why she reacted negatively to Al and Margie’s story.

The trail was narrow and she walked behind Bert, not wanting to set a pace that put too much strain on his injured ankle. She heard someone behind her and realized she was being overtaken by another hiker. Moving off the trail slightly and slowing, she did what she could to let the person pass. She turned slightly as he went by and caught a quick glimpse. Her breath caught in her throat. For an ever-so-brief instant, she thought it was her dad—the one who had raised her. She’d heard of people having that experience, but it never happened to her before and she’d never quite believed it was possible. It must have been this thinking! A second later she realized he didn’t even look much like him. “Danke, buen Camino,” he said as he passed her. The adrenalin rush did not pass with him. She had seen a ghost. Camino magic? She wanted him to be real. She knew he wasn’t. Another set of never-visited thoughts cascaded out of her subconscious.

She remembered that when her dad died, she felt herself being angry with him. Totally illogical and unlike her, but there it was. She was angry that he just up and had a heart attack and died. The anger didn’t last long, a few months maybe. What remained after the anger was a bittersweet sadness. Without warning the sadness would well up in her and tears would flow. Sometimes it seemed there was no trigger. Other times, it would be that she wished she could call and tell him something, and he would share her joy and be proud for her. She had never really called like that, impulsively, to share something, before he died. She was always afraid she’d interrupt him or bother him. The thought reminded her of what Margie had said about meeting Al at the reunion, and how she was afraid he would reject her.

Bert, who had been walking a few yards ahead, stood by the trail. When she reached him, she stopped, and together they looked down a steep slope to where a large flock of sheep, surely more than a hundred, were filing along a path below. Most followed the path as if it were a familiar one, with little or no attention from the single shepherd and his small dog.

“There’s a scene you won’t see in Florida or DC,” said Bert, as they resumed picking their way along the trail.

Ah, yes, Florida. Her thoughts drifted to work. What if she didn’t want to just ride the wave into retirement? She wondered if she had peaked too early and all the rest of her days would be like walking down this mountain. Sure it was beautiful, but more tortuous than the climbing up had been.

Having all this time to be inside her own head might be a gift from the universe right at the moment when she could best take advantage of it. For the first time she let herself think about the call from Donald. Maybe before they specifically asked her to come to headquarters, she could apply for some other position she’d like better. She ought to have a good shot at becoming the manager of a more important refuge. Or, maybe she could overcome her gut feelings and enjoy the policy position he implied they wanted her to take. Maybe she could influence the whole system somehow.

“What is going on in my head today? How did I get into this whole discussion with myself?” She said this out loud, perhaps to more effectively banish the jumble of ideas. The attempt failed. The notion slipped in that if she wanted something new, something more, it might be in a corner of her life that was not about work. Maybe she ought to listen to what her subconscious was whispering. Or was it shouting when it brought recollections of Greg and her dad into this day of Camino color, spirit, and magic? Unlike the tearful pilgrim leaving his burden up there at the Cruz de Ferro, for her the place had done something else. Somehow it had let hidden burdens burst into the open.

She felt the juxtaposition of the joy of the past months and the other joys—those foregone—along paths she had not chosen. She’d always believed she had to make careful choices. Love the dad the universe gave her, or be sad about the father who had left her before she met him. Accept that Greg was rejecting the woman she really was, or become someone she really wasn’t to avoid the divorce. Take the new refuge and hope to make a go of it, or stay in a less risky job. And Bert’s friendship, what was the choice she was making there? She wondered if there is an age when you face down the choices, mistakes, and regrets of the past. She wondered if there is an age when you stop having to choose one thing over another. She wondered if she was old enough yet to do more than one thing at a time for a change. The thought fit the spirit of the day.

__________

Wednesday, June 15 3:02 PM

To: task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Cc: Maureen327@midnet.net, Donna121@midnet.net

From: bert_task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Subject: Camino Report #6

Dear Friends,

I am happy to report that we are in the small city of Molinaseca. Not only has the place provided good access to the Internet, but we have now gotten through what has been some rather difficult hiking. The guidebook shows the steep descent is behind us, thank goodness, and I’m expecting a couple of days with relatively level ground and, I hope, well-developed trails. My healing seems to be advancing apace, but a repeat mishap and re-injury would not help.