|

You can read this section of the book here on screen, or use the buttons to download it as a PDF or Word file to read on another devise.

|

|

Second Wind on the Way of St. James

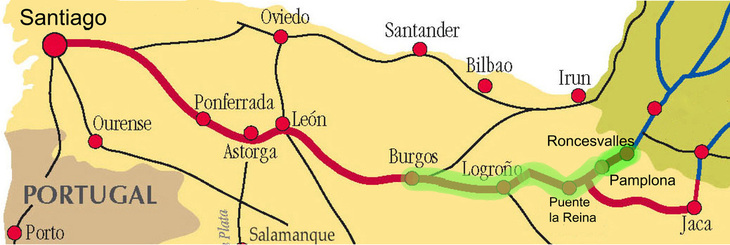

© 2013 by Russell J Hall and Peg Rooney Hall Published by: Lighthall Books P.O. Box 357305 Gainesville, Florida 32635-7305 http://www.lighthallbooks.com Orders: gem@lighthallbooks.com No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, either electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, except as specified by the authors. Electronic versions made available free of charge are intended for personal use, and may not be offered for sale in any form except by the authors. Excluded from copyright are the maps, which are based on the work of Manfred Zentgraf of Volkach, Germany. Like the original, our adaptations of his map remain in the public domain. Second Wind is a work of fiction. Many experiences of the authors on the Camino have inspired and informed themes of the book, but people and events depicted are products of the authors’ imaginations; any resemblance to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental. |

Episode 3

Stage Three:

The Hard Road

Logrono to Burgos

Poor in Spirit

Logrono to Navarette

Sunday, May 22

Walking out of Logroño after a relaxing afternoon, seven days were now behind them. The light brown gravel trail was dry and flat. Pleasant, low-rise apartment buildings lined the broad park-like district through which they walked. Bicycles were allowed on the wide trail, but cars were off somewhere else, unseen. Bert noted that the miles seemed shorter along this stretch where the walking was more comfortable.

They arrived at a lake, crowded with families enjoying a Sunday of fishing and picnicking. On the far side, the route climbed. Bert was pleased that his body did not rebel.

They came to a café with a terrace looking down on the lake. He was more than content to rest a bit and agreed immediately when Helen suggested they get a café con leche and something to eat. A French couple they had spoken with earlier wandered in their direction and Bert motioned them to join him, but they explained in their labored English that their destination was a pharmacy a few streets over.

Helen went to get their coffee while he stayed with their packs. He was gazing blankly at a group of hikers sitting outside the café when a young woman on a bench opposite him caught his attention. He couldn’t imagine how she managed it, but somehow she was changing out of a pair of long pants and into shorts in plain sight, while he had been looking in her direction. Fascinated, he tried to take in the scene while appearing not to be looking, although it seemed not to matter to her in the least that a man sat facing her not ten feet away. She probably knew exactly what she was doing, he concluded, because she wriggled out of one garment into another while showing a minimal amount of skin and nary a hint of underwear. She had a little Swedish flag stitched on her backpack. That made sense; it didn’t surprise him that a Swedish woman would undress in the open. On the other hand, he found it surprising and disappointing that she had been able to pull off the feat so modestly.

One thing that could be said about the Camino is that so far it had an unending ability to surprise in small and large ways.

As the Swedish woman had completed her change of wardrobe and was strapping herself into her heavy-looking pack, he noticed her long and muscular legs. Suspecting that she was an athletic hiker probably each day knocking down thirty or more kilometers—that would be at least twenty miles—he gave up any thought of seeing her again.

He enjoyed the rest and coffee. Before hitting the trail again, Helen wanted to visit the restroom, which at the moment had a three-person waiting line. He felt lucky knowing that if he needed a pit stop once they were on the trail, he would surely be able to find a convenient clump of tall shrubs with no waiting line. Her desire to take a bit of extra time did not make him unhappy because he saw ten more minutes of sitting as a means of further restoring life to his legs.

He was staring at his empty coffee cup when a man came over and asked in English if he might sit down at Helen’s vacated place, then the only available chair in the café. “Of course,” Bert replied, pushing Helen’s pack and walking poles to the side, “we’ve finished and will be leaving soon.”

They exchanged the usual pleasantries. Conrad was from Geneva in Switzerland. Apparently in his early sixties, he explained that his flawless English was the result of many years of study and many happy hours spent with his Irish daughter-in-law. Stocky, with tiny rimless glasses, and dressed in forest green, he could have played the part of an Alpine gentleman in a Hollywood movie. Bert did allow that his gold earring might have spoiled the effect.

It became almost immediately clear that Conrad was as much interested in conversation as in the cup of coffee he cradled between his hands.

“I have been noticing that the people I see here on the Camino are quite different from the people one sees in everyday life,” he said.

“I suppose they are a special breed,” Bert replied, readily agreeing but not quite sure what the other man meant.

“I am retired now, but in my career I was in social services. I worked with people who require assistance from the state. You know, the welfare office. We did a good job in helping out many deserving people who were just overcome by misfortune. But some of the people, they were—I am sure you have them in America also—they were hopeless. They were hopeless in two ways. First they never changed, and any hopes we in the office might have that our help would improve them were never met. We had no hope for them.

“Also they were hopeless because they had no hope for their own lives. I don’t mean to exaggerate, but this is how it was with all but the smallest percentage of those clients. They had, many of them anyway, had damaged lives. We tried to help them, of course, but we could do nothing that would really change their affairs. Whatever we tried to do, in the end their lives remained unchanged.”

“Yes, I’ve known some people like that, I guess. But I never thought of it the way you described it,” said Bert, his mind roaming to the fringes of his own family. A cousin on his mother’s side came to mind immediately.

“I think of them as ’poor people,’ but it is not about money. Not all people with too little money fit my category. Those I think of as ‘poor people’ seem to have a limited view of the world and their lives. They see their lives as they are, and they accept whatever they see. Their thinking seems to be: I have a drug problem, I am overweight, I am unemployed, my spouse isn’t good for me, and my children are making all the mistakes I made. Of course, they seem to think, that is just the way things are. They see all of these things and they say, ‘yes, that is my life,’ and they do nothing to change it.”

“I see what you mean,” Bert said, “but all the people who came into your office couldn’t have been like that, could they? I can’t imagine everyone who needed help was like that. Some must just have had a disaster that messed up their lives, like a business going bad or something. They need help to get back to normal. And what about mental illness? Aren’t some of them mentally ill?”

“Yes, some of them are ill or in a crisis,” replied Conrad, “but most of them are not. They are poor in spirit. It has very little to do with the idea of spirituality, the way the people here on the Camino consider it. Instead our clients were passive and seemed to be . . .Um—I don’t know—they might have good times or bad times, but that made no difference because they saw no connection between what they did, and what happened to them and their lives, or the lives of people around them.”

The Biblical saying about the poor in spirit inheriting the earth came to mind for Bert. Maybe that wasn’t it exactly; there was also something about the meek and seeing God. Somehow the Biblical idea of the poor in spirit inheriting the earth wasn’t comforting.

“So you’re saying . . . Let me try to say this right. Unlike people you’ve been talking about, those who feel no responsibility for what happens to them, the people you have met on the Camino may have problems of various kinds or find their lives lacking in some way, but they’re not being passive or indifferent because they are doing something about it. They are seeking some kind of answer or solution, and walking the Camino is a part of it.”

“Exactly,” said Conrad. “If all humans were like the people I have met on the Camino, then I would not have had a career, or at least I would have had a different one. Maybe I would have become a foot doctor. Ha, ha! But making jokes aside, the world would be a better place because it would be filled with people who are living better lives.”

“I don’t think everyone I have met here in Spain is dealing with a problem or feels something lacking in his or her life,” said Bert. “My friend Helen, for example, is celebrating having had a series of successes at work this year. But, I think you’re right that everyone is doing it for a reason, and the fact that they are doing it certainly indicates that they aren’t being passive. Willingly pulling on boots, often damp ones, every morning and trudging off to the trail, often a wet trail, on sore feet wouldn’t happen to them if they were passive people.”

“You’re right. We are not all here to work out problems. But we certainly would not be here if we were the passive types,” Conrad replied.

Bert easily followed the logic of what Conrad was saying about people walking the Camino, but his own situation didn’t seem to fit. The only reason he was here was that Helen had encouraged, almost demanded, that he do it. And, he still thought she probably needed him to make it possible for her to come. He couldn’t believe she would have done it alone. There must be many others just like him, walking because of a friend or family member.

Just then, Helen returned. Bert introduced Conrad while he and Helen were putting on their backpacks and getting ready to leave.

“I hope we’ll meet again and can continue our conversation,” said Bert as they parted.

“What was your conversation about?” They were back on the trail, and he couldn’t tell whether Helen was truly curious or just making small talk.

“It had to do with the temperament of people walking the Camino. It piqued my curiosity. I need to think about it more. I’d like to hear your take on it, but that’ll have to wait until I’ve thought about it a bit longer. Were there any interesting conversations to liven up your time with your colleagues in the queue for the W.C.?”

“I suppose I could have engaged them in speculation about the likelihood that toilet paper would be available once we reached our destination, but no one seemed particularly talkative, despite the liveliness and timeliness of the potential conversation topic. By the way, toilet paper was available and I didn’t have to use the stash I had in my pocket.”

Rejoicing in the lovely flat fields and vineyards they were crossing, Bert’s mind was at ease and freely wandered to thoughts about the cousin Conrad’s words had brought to mind. He couldn’t imagine what made Ellie the way she was, but she was surely one of life’s losers. He liked Conrad’s language about “poor in spirit.” That was kinder and less judgmental than “loser,”’ and he preferred to think about Ellie in a gentler way. She had been good enough to him, and surely she hadn’t wanted to be a loser, so some deeper cause must have been involved.

She had almost all the symptoms Conrad had mentioned. She apparently had multiple drug dependencies, was overweight, couldn’t or wouldn’t hold a job. Her house was a mess, and most of the time she was a mess. She had what these days we’d call a domestic partner who was prone to violence and currently was serving a jail term, and her four children clearly had not had good role models. Three of the children showed every indication of reliving the lifestyle pioneered by their mother. No one in the wider family doubted that more than one man was responsible for fathering her children, not the least because one daughter, Carla, had surprised everyone. She had broken with family tradition, and seemed on a trajectory to finish college with outstanding grades and bright prospects.

A slight smile crossed Bert’s lips when he remembered the old rural metaphor. Maybe inside whatever fence Ellie usually found herself there were only potential mates with unpromising genes. It would be nice to think she managed to “jump the fence” and for once after an unbroken series of unfortunate liaisons to link up with a man who was the source of some promising genes. On the other hand, he realized, the metaphor didn’t entirely fit, because Ellie seemed never to have been constrained by fences of any kind. Carla’s success was inspiring, all the more so because her mother’s successes were so few; after all, her average was only one in four when it came to finding suitable mating partners.

Who could ignore the contrast between Ellie, her incarcerated husband, and her train-wreck brood on one hand, and the overachiever Carla on the other? He liked imagining there could be a gene that was needed for success, and another gene or lack thereof that would condemn one to a lifetime of skidding along one downslope after another. Maybe it is all in the genes, he laughed to himself, aware as a biologist that few qualities of human lives are determined by one or even a few genes. He could think of no rational explanation for how things had developed for Ellie.

Enough fantasy! He would think about something else. Navarette was just ahead, and his mind turned to how nice it was that they planned another short day of walking.

Entering the town, they were treated to more stork nests, one on top of the large chimney of an old factory, and the others perched precariously on a ledge of a tall church steeple.

Later as they were sipping wine at one of the outdoor tables of a café on the plaza, he posed a question to Helen. “What does the term ‘poor in spirit’ mean to you?”

“You mean blessed are the poor in spirit because theirs is the kingdom of heaven?”

Puzzled, Bert wondered if the surprise showed in his face. He leaned forward so as not to miss the expected explanation.

“One more thing you don’t know about me, Mr. Charles! I was a nun in a former life.”

Not looking at him, she reached for one of the olives on the plate the waiter had set in front of them when he brought their wine.

“Okay, I wasn’t a nun, and as far as I know, I haven’t had a former life. I was just pretending to be Shirley MacLaine for a moment,” she said with a wink and a smile. “I took a course about the Bible in college—you know, a Bible as history and culture kind of course. That particular statement is a big one for Bible-study people, because it seems to make little sense. From what I remember, their explanation for the apparent contradiction is that ‘poor in spirit’ equates more or less to ‘humble.’ I suppose they see that in a good sense, like devout monks living in poverty and humility.”

She went on. “That would be a reasonable interpretation if you were trying to avoid an apparent paradox. But what if the words in the Bible mean exactly what they say? Many Christians insist that they do.”

“Conrad, the Swiss guy I talked to at the last café, used the term to apply to the clients he had when he was working for a social welfare agency. I’m dubbing him, Poor in Spirit Conrad. I think he uses it to mean that they are lacking something. I suppose you could call it spirit. I do wonder about people who can’t seem to live their lives properly, and I’ve got a not-too-distant example in my own family.”

“You and everybody else, I suppose.”

“My cousin Ellie is one of those people who have never gotten their acts together,” said Bert. “Nothing she has ever done appears to have made her happy. I don’t even think she expected the things she did would make her happy. If she had wanted to be happy, she would have followed a completely different path. She wouldn’t have taken wrong turns at every opportunity.”

“Bert, I don’t think we’ll ever know what motivates some people. We don’t even fully understand ourselves, I’d bet. Why do you think the idea resonates with you?”

He brushed two flies off the edge of the plate, ate a couple of olives, and sat back, drinking his wine. After a minute, Helen asked if he had heard her.

“Maybe Ellie didn’t think happiness was possible. Maybe she thought she could never be happy. So at some point, at some critical point in her life, she gave up trying. I don’t know about you, Helen, but to me that is really the meaning of poor in spirit.”

“I’d have to agree, for sure,” said Helen. “I’ve never heard you talk about your family before, other than to tell me that you weren’t particularly close to any of them. Have I been missing something? Is there more of a story than you led me to believe?”

“Not really,” Bert replied after another sip of his wine. “As you know, my folks were pretty old when I was born and my brother and sister had long ago left home. My mother used to visit her siblings and their families now and then, and sometimes she dragged me along. I suppose looking in at those people, they almost didn’t seem real. I was so much younger than any of them. Watching them and hearing about what they did—I don’t know—it was sort of like reading a novel. They didn’t seem connected to me. I just peeked into their lives. Like most people, I expect, I would get curious about what made them tick.”

“But you did care about them, at least a little bit?”

“I suppose, but I cared about the Hardy Boys too.”

They both laughed at that.

“Well, we figured out the Bible’s true meaning. We got our minds around Poor in Spirit Conrad’s use of a turn of phrase. We analyzed your cousin Ellie. And voila! We still have a half-bottle of wine sitting in front of us.”

Bert smiled and offered a toast.

“To Conrad, the Camino, and the two of us,” said Bert, holding up his wine glass. “Maybe by the time we get to Santiago we’ll be world-class philosophers.”

Helen’s eye caught a swinging ponytail, and then recognized a familiar hiker passing by. It was Ilsa, the Australian biologist they’d met in Puente la Reina. “Join us, Ilsa. It is good to see you again.”

“May we join you too,” asked a man with a British accent. “There is a shortage of tables.”

“Of course, plenty of chairs here,” replied Bert. Just then a white haired man wandered by, apparently also looking for a chair and they waved him into their little group.

“Je ne parle pas anglais,” he said.

“Je parle un peu de franςais,” Helen replied.

“Moi aussi,” said Ilsa. “Asseyez-vous.”

Ilsa’s French was excellent. Bert noticed that, while the others chatted in English, Helen appeared to enjoy being part of the conversation in French about the day’s walk. After a glass of wine, the Frenchman excused himself to meet up with some friends for dinner. The rest of them decided to find a restaurant together.

As the small group set off in search of a meal, it struck Bert that if he were one of those desperate people who walk the Camino in search of companionship, he would have found it tonight.

__________

Sunday, May 22 5:45 PM

To: task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Cc: Maureen327@midnet.net, Donna121@midnet.net

From: bert_task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Subject: Camino Report #2

Dear Fellow Task Force Members,

In the seven days since my last note I have learned many things. For one, when you spend your days walking, weather is really important. And for another, when you walk downhill for a long time, your toes get sore. Who knew? Fortunately, we have had several sunny days and no all-day rainy ones. The trail was much harder those first few days when it was muddy from rain the week before we arrived here and much more hilly than we expected. Now it has flattened and having the sun shine most of the time is as good for the spirits as it is for the trail underfoot.

We’re in the town of Navarette. To satisfy your curiosity, I’ll touch on some of the highlights of the past days.

Not long after leaving Pamplona we joined a Roman road, which was still more or less serviceable after apparently having not been maintained for the past 1,500 years or so. We walked over a bridge that Caesar Augustus crossed in 27 B.C. on his way to the Cantabrian wars.

One of the mornings we stopped at a roadside water station. They are common here and useful for stocking up on potable water along the way. This one was different—unique in fact—because there were two spigots and they were on the outside wall of a bodega—a large winery. The second spigot was dispensing free wine to walkers. Unfortunately it was still quite early and, tempting as it was, we resisted the urge to drain out our water bottles and refill them with wine. Too bad more places like that haven’t shown up.

The countryside has been hilly with some low mountains, which can be remarkably challenging when the ascent and descent are steep. The more moderate hills are covered with fields of grain. The scenery is not spectacular, but consistently nice with wild poppies often lining the trail. At one point we came upon an incongruity in the form of a Kraft Foods factory. We couldn’t tell what it was producing, but it probably wasn’t cheese, and must have had something to do with grain because no dairying is evident in this part of the country.

Shortly before Logroño there was a natural area that featured a restored wetland and nice storyboards about the birds and other wildlife that are benefiting from it. A short distance down the trail another sign announced that witchcraft was common in the area in the sixteenth century, and the field that was flooded to form the lake was famous as a gathering place for witches.

We entered Logroño and simultaneously the La Rioja district, famous worldwide for production of top-quality and well-regarded wines. We had a nice long day there because the walk from the monastery where we stayed (more about that below) was only about six miles. We were ready for a partial rest day and there is much to see there, including a Gothic cathedral built on a Romanesque base. We strolled the plazas and looked at the shops. Since there are good train and bus connections to Logroño, we could have bailed out and headed for the beach for the rest of the time. But gluttons for punishment, we decided neither of us was ready to bail just yet. I surprised myself by deciding to keep going. I was happy that my walking companion wanted to stick with it too. In those first few jet-lagged days I felt that she was disappointed in this grand plan she concocted. I guess she is back to normal now.

A little more about the night before last. We had a quite remarkable monastery experience. Helen had found a little-known monastery not far from town and we decided to give it a try. Unlike the monastery in Roncesvalles, this one was a trip back to the Middle Ages, replete with an antique nun questioning marital status of guests. The monastery also provided an intriguing pilgrim blessing by the whole congregation of nuns, who ranged in age from about 85 to 95 with the exception of one about 30 or more years their junior. I decided she is going to be the last nun standing and own the whole place in a few years.

When we left the city, we followed a long pedestrian way through a park. There were miles of hiking-cycling trail with no cars, trucks, buses, or motorcycles. Not that bicycles aren’t serious hazards to pedestrians, but at least they are less noisy than cars. Men and boys here are into cycling. Very few women and girls do it. The trail took us to a lake where many were fishing and picnicking. Lots of cars there, but luckily they did not share our route. They were also giving hot-air balloon rides at the park. We kept our feet on the ground.

Soon after the park we were out of the city. I was grateful to the city fathers (mothers?) for giving us that lovely walk instead of making us walk through suburban streets for hours.

The landscape that had been dominated by wheat fields before Logroño was transformed into one dominated by vineyards. The walking was pleasant, although despite all my training and preparation, by the end of a day’s walk my feet are very sore. My pack fits well, but the extra weight has made itself known by the stress it has put on my knees. The walking poles help a lot, but my left knee in particular feels as if it could give out on me at any time. Until that happens, I’ll keep on.

As you can tell from the above, a few nice experiences have tended to balance the hardships somewhat. I’m hoping for more highlights in the days to come, and to overcome my persistent physical infirmities. I would not yet recommend this vacation to a friend, so stay tuned and I’ll let you know after I’ve had more time to adapt. I can say that walking 500 miles probably isn’t for everyone, so if cruise ships appeal to you, don’t even think about this.

I appreciate your not bothering me with phone calls, Team, but I am continuing to monitor all the e-mails on my Blackberry, and I’ll be available whenever needed. I did like Ted’s suggestion about the filtering protocol and have a few more thoughts to share whenever he has time to listen to them.

Still walking,

Bert

PS. The Maureen and Donna who are copied on this message are Helen’s sisters. Helen asked me to include them since my description is so perfect she couldn’t tell our story any better. I trust that using my government e-mail account for these essentially personal messages isn’t a breach of the rules. If it is, I will leave it to one of you or somebody in the IT office to let me know. How’s that for a proactive c.y.a.?

___________

Sunday, May 22 6:12 PM

To: Maureen327@midnet.net, Donna121@midnet.net

From: Helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Not quite perfect

Maureen and Donna,

Bert really did write a great description of our journey so far, not that it was as perfect as he thinks. I would second everything he wrote about the trail and the monastery. On the other hand, I can’t imagine what made him think I was so discouraged those first few days. At any rate, wrong though he was about that, he is right that we are both feeling stronger and finding the walking less difficult. We are off now to meet some hiker friends for dinner, an Australian biology professor and a couple from England.

Helen the hiker

__________

Sunday, May 22 6:26 PM

To: Dan@northpinerefuge.gov

From: Helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Checking In

Dan,

Now that you have the gang up off their duffs, I am sure all is going well under your leadership. I appreciate your willingness to take over while I am away. I am able to check e-mail every few days, and if you need something, I will respond as quickly as possible. The hike is going well. We have covered about a hundred miles so far. Funny that it takes a whole day to go as far as you could drive in half an hour, but you certainly see a lot more on foot. We might even know what birds we were looking at if we had an identification guide. You know . . . all those little brown birds you see out the window when driving sixty miles per hour.

Helen

They arrived at a lake, crowded with families enjoying a Sunday of fishing and picnicking. On the far side, the route climbed. Bert was pleased that his body did not rebel.

They came to a café with a terrace looking down on the lake. He was more than content to rest a bit and agreed immediately when Helen suggested they get a café con leche and something to eat. A French couple they had spoken with earlier wandered in their direction and Bert motioned them to join him, but they explained in their labored English that their destination was a pharmacy a few streets over.

Helen went to get their coffee while he stayed with their packs. He was gazing blankly at a group of hikers sitting outside the café when a young woman on a bench opposite him caught his attention. He couldn’t imagine how she managed it, but somehow she was changing out of a pair of long pants and into shorts in plain sight, while he had been looking in her direction. Fascinated, he tried to take in the scene while appearing not to be looking, although it seemed not to matter to her in the least that a man sat facing her not ten feet away. She probably knew exactly what she was doing, he concluded, because she wriggled out of one garment into another while showing a minimal amount of skin and nary a hint of underwear. She had a little Swedish flag stitched on her backpack. That made sense; it didn’t surprise him that a Swedish woman would undress in the open. On the other hand, he found it surprising and disappointing that she had been able to pull off the feat so modestly.

One thing that could be said about the Camino is that so far it had an unending ability to surprise in small and large ways.

As the Swedish woman had completed her change of wardrobe and was strapping herself into her heavy-looking pack, he noticed her long and muscular legs. Suspecting that she was an athletic hiker probably each day knocking down thirty or more kilometers—that would be at least twenty miles—he gave up any thought of seeing her again.

He enjoyed the rest and coffee. Before hitting the trail again, Helen wanted to visit the restroom, which at the moment had a three-person waiting line. He felt lucky knowing that if he needed a pit stop once they were on the trail, he would surely be able to find a convenient clump of tall shrubs with no waiting line. Her desire to take a bit of extra time did not make him unhappy because he saw ten more minutes of sitting as a means of further restoring life to his legs.

He was staring at his empty coffee cup when a man came over and asked in English if he might sit down at Helen’s vacated place, then the only available chair in the café. “Of course,” Bert replied, pushing Helen’s pack and walking poles to the side, “we’ve finished and will be leaving soon.”

They exchanged the usual pleasantries. Conrad was from Geneva in Switzerland. Apparently in his early sixties, he explained that his flawless English was the result of many years of study and many happy hours spent with his Irish daughter-in-law. Stocky, with tiny rimless glasses, and dressed in forest green, he could have played the part of an Alpine gentleman in a Hollywood movie. Bert did allow that his gold earring might have spoiled the effect.

It became almost immediately clear that Conrad was as much interested in conversation as in the cup of coffee he cradled between his hands.

“I have been noticing that the people I see here on the Camino are quite different from the people one sees in everyday life,” he said.

“I suppose they are a special breed,” Bert replied, readily agreeing but not quite sure what the other man meant.

“I am retired now, but in my career I was in social services. I worked with people who require assistance from the state. You know, the welfare office. We did a good job in helping out many deserving people who were just overcome by misfortune. But some of the people, they were—I am sure you have them in America also—they were hopeless. They were hopeless in two ways. First they never changed, and any hopes we in the office might have that our help would improve them were never met. We had no hope for them.

“Also they were hopeless because they had no hope for their own lives. I don’t mean to exaggerate, but this is how it was with all but the smallest percentage of those clients. They had, many of them anyway, had damaged lives. We tried to help them, of course, but we could do nothing that would really change their affairs. Whatever we tried to do, in the end their lives remained unchanged.”

“Yes, I’ve known some people like that, I guess. But I never thought of it the way you described it,” said Bert, his mind roaming to the fringes of his own family. A cousin on his mother’s side came to mind immediately.

“I think of them as ’poor people,’ but it is not about money. Not all people with too little money fit my category. Those I think of as ‘poor people’ seem to have a limited view of the world and their lives. They see their lives as they are, and they accept whatever they see. Their thinking seems to be: I have a drug problem, I am overweight, I am unemployed, my spouse isn’t good for me, and my children are making all the mistakes I made. Of course, they seem to think, that is just the way things are. They see all of these things and they say, ‘yes, that is my life,’ and they do nothing to change it.”

“I see what you mean,” Bert said, “but all the people who came into your office couldn’t have been like that, could they? I can’t imagine everyone who needed help was like that. Some must just have had a disaster that messed up their lives, like a business going bad or something. They need help to get back to normal. And what about mental illness? Aren’t some of them mentally ill?”

“Yes, some of them are ill or in a crisis,” replied Conrad, “but most of them are not. They are poor in spirit. It has very little to do with the idea of spirituality, the way the people here on the Camino consider it. Instead our clients were passive and seemed to be . . .Um—I don’t know—they might have good times or bad times, but that made no difference because they saw no connection between what they did, and what happened to them and their lives, or the lives of people around them.”

The Biblical saying about the poor in spirit inheriting the earth came to mind for Bert. Maybe that wasn’t it exactly; there was also something about the meek and seeing God. Somehow the Biblical idea of the poor in spirit inheriting the earth wasn’t comforting.

“So you’re saying . . . Let me try to say this right. Unlike people you’ve been talking about, those who feel no responsibility for what happens to them, the people you have met on the Camino may have problems of various kinds or find their lives lacking in some way, but they’re not being passive or indifferent because they are doing something about it. They are seeking some kind of answer or solution, and walking the Camino is a part of it.”

“Exactly,” said Conrad. “If all humans were like the people I have met on the Camino, then I would not have had a career, or at least I would have had a different one. Maybe I would have become a foot doctor. Ha, ha! But making jokes aside, the world would be a better place because it would be filled with people who are living better lives.”

“I don’t think everyone I have met here in Spain is dealing with a problem or feels something lacking in his or her life,” said Bert. “My friend Helen, for example, is celebrating having had a series of successes at work this year. But, I think you’re right that everyone is doing it for a reason, and the fact that they are doing it certainly indicates that they aren’t being passive. Willingly pulling on boots, often damp ones, every morning and trudging off to the trail, often a wet trail, on sore feet wouldn’t happen to them if they were passive people.”

“You’re right. We are not all here to work out problems. But we certainly would not be here if we were the passive types,” Conrad replied.

Bert easily followed the logic of what Conrad was saying about people walking the Camino, but his own situation didn’t seem to fit. The only reason he was here was that Helen had encouraged, almost demanded, that he do it. And, he still thought she probably needed him to make it possible for her to come. He couldn’t believe she would have done it alone. There must be many others just like him, walking because of a friend or family member.

Just then, Helen returned. Bert introduced Conrad while he and Helen were putting on their backpacks and getting ready to leave.

“I hope we’ll meet again and can continue our conversation,” said Bert as they parted.

“What was your conversation about?” They were back on the trail, and he couldn’t tell whether Helen was truly curious or just making small talk.

“It had to do with the temperament of people walking the Camino. It piqued my curiosity. I need to think about it more. I’d like to hear your take on it, but that’ll have to wait until I’ve thought about it a bit longer. Were there any interesting conversations to liven up your time with your colleagues in the queue for the W.C.?”

“I suppose I could have engaged them in speculation about the likelihood that toilet paper would be available once we reached our destination, but no one seemed particularly talkative, despite the liveliness and timeliness of the potential conversation topic. By the way, toilet paper was available and I didn’t have to use the stash I had in my pocket.”

Rejoicing in the lovely flat fields and vineyards they were crossing, Bert’s mind was at ease and freely wandered to thoughts about the cousin Conrad’s words had brought to mind. He couldn’t imagine what made Ellie the way she was, but she was surely one of life’s losers. He liked Conrad’s language about “poor in spirit.” That was kinder and less judgmental than “loser,”’ and he preferred to think about Ellie in a gentler way. She had been good enough to him, and surely she hadn’t wanted to be a loser, so some deeper cause must have been involved.

She had almost all the symptoms Conrad had mentioned. She apparently had multiple drug dependencies, was overweight, couldn’t or wouldn’t hold a job. Her house was a mess, and most of the time she was a mess. She had what these days we’d call a domestic partner who was prone to violence and currently was serving a jail term, and her four children clearly had not had good role models. Three of the children showed every indication of reliving the lifestyle pioneered by their mother. No one in the wider family doubted that more than one man was responsible for fathering her children, not the least because one daughter, Carla, had surprised everyone. She had broken with family tradition, and seemed on a trajectory to finish college with outstanding grades and bright prospects.

A slight smile crossed Bert’s lips when he remembered the old rural metaphor. Maybe inside whatever fence Ellie usually found herself there were only potential mates with unpromising genes. It would be nice to think she managed to “jump the fence” and for once after an unbroken series of unfortunate liaisons to link up with a man who was the source of some promising genes. On the other hand, he realized, the metaphor didn’t entirely fit, because Ellie seemed never to have been constrained by fences of any kind. Carla’s success was inspiring, all the more so because her mother’s successes were so few; after all, her average was only one in four when it came to finding suitable mating partners.

Who could ignore the contrast between Ellie, her incarcerated husband, and her train-wreck brood on one hand, and the overachiever Carla on the other? He liked imagining there could be a gene that was needed for success, and another gene or lack thereof that would condemn one to a lifetime of skidding along one downslope after another. Maybe it is all in the genes, he laughed to himself, aware as a biologist that few qualities of human lives are determined by one or even a few genes. He could think of no rational explanation for how things had developed for Ellie.

Enough fantasy! He would think about something else. Navarette was just ahead, and his mind turned to how nice it was that they planned another short day of walking.

Entering the town, they were treated to more stork nests, one on top of the large chimney of an old factory, and the others perched precariously on a ledge of a tall church steeple.

Later as they were sipping wine at one of the outdoor tables of a café on the plaza, he posed a question to Helen. “What does the term ‘poor in spirit’ mean to you?”

“You mean blessed are the poor in spirit because theirs is the kingdom of heaven?”

Puzzled, Bert wondered if the surprise showed in his face. He leaned forward so as not to miss the expected explanation.

“One more thing you don’t know about me, Mr. Charles! I was a nun in a former life.”

Not looking at him, she reached for one of the olives on the plate the waiter had set in front of them when he brought their wine.

“Okay, I wasn’t a nun, and as far as I know, I haven’t had a former life. I was just pretending to be Shirley MacLaine for a moment,” she said with a wink and a smile. “I took a course about the Bible in college—you know, a Bible as history and culture kind of course. That particular statement is a big one for Bible-study people, because it seems to make little sense. From what I remember, their explanation for the apparent contradiction is that ‘poor in spirit’ equates more or less to ‘humble.’ I suppose they see that in a good sense, like devout monks living in poverty and humility.”

She went on. “That would be a reasonable interpretation if you were trying to avoid an apparent paradox. But what if the words in the Bible mean exactly what they say? Many Christians insist that they do.”

“Conrad, the Swiss guy I talked to at the last café, used the term to apply to the clients he had when he was working for a social welfare agency. I’m dubbing him, Poor in Spirit Conrad. I think he uses it to mean that they are lacking something. I suppose you could call it spirit. I do wonder about people who can’t seem to live their lives properly, and I’ve got a not-too-distant example in my own family.”

“You and everybody else, I suppose.”

“My cousin Ellie is one of those people who have never gotten their acts together,” said Bert. “Nothing she has ever done appears to have made her happy. I don’t even think she expected the things she did would make her happy. If she had wanted to be happy, she would have followed a completely different path. She wouldn’t have taken wrong turns at every opportunity.”

“Bert, I don’t think we’ll ever know what motivates some people. We don’t even fully understand ourselves, I’d bet. Why do you think the idea resonates with you?”

He brushed two flies off the edge of the plate, ate a couple of olives, and sat back, drinking his wine. After a minute, Helen asked if he had heard her.

“Maybe Ellie didn’t think happiness was possible. Maybe she thought she could never be happy. So at some point, at some critical point in her life, she gave up trying. I don’t know about you, Helen, but to me that is really the meaning of poor in spirit.”

“I’d have to agree, for sure,” said Helen. “I’ve never heard you talk about your family before, other than to tell me that you weren’t particularly close to any of them. Have I been missing something? Is there more of a story than you led me to believe?”

“Not really,” Bert replied after another sip of his wine. “As you know, my folks were pretty old when I was born and my brother and sister had long ago left home. My mother used to visit her siblings and their families now and then, and sometimes she dragged me along. I suppose looking in at those people, they almost didn’t seem real. I was so much younger than any of them. Watching them and hearing about what they did—I don’t know—it was sort of like reading a novel. They didn’t seem connected to me. I just peeked into their lives. Like most people, I expect, I would get curious about what made them tick.”

“But you did care about them, at least a little bit?”

“I suppose, but I cared about the Hardy Boys too.”

They both laughed at that.

“Well, we figured out the Bible’s true meaning. We got our minds around Poor in Spirit Conrad’s use of a turn of phrase. We analyzed your cousin Ellie. And voila! We still have a half-bottle of wine sitting in front of us.”

Bert smiled and offered a toast.

“To Conrad, the Camino, and the two of us,” said Bert, holding up his wine glass. “Maybe by the time we get to Santiago we’ll be world-class philosophers.”

Helen’s eye caught a swinging ponytail, and then recognized a familiar hiker passing by. It was Ilsa, the Australian biologist they’d met in Puente la Reina. “Join us, Ilsa. It is good to see you again.”

“May we join you too,” asked a man with a British accent. “There is a shortage of tables.”

“Of course, plenty of chairs here,” replied Bert. Just then a white haired man wandered by, apparently also looking for a chair and they waved him into their little group.

“Je ne parle pas anglais,” he said.

“Je parle un peu de franςais,” Helen replied.

“Moi aussi,” said Ilsa. “Asseyez-vous.”

Ilsa’s French was excellent. Bert noticed that, while the others chatted in English, Helen appeared to enjoy being part of the conversation in French about the day’s walk. After a glass of wine, the Frenchman excused himself to meet up with some friends for dinner. The rest of them decided to find a restaurant together.

As the small group set off in search of a meal, it struck Bert that if he were one of those desperate people who walk the Camino in search of companionship, he would have found it tonight.

__________

Sunday, May 22 5:45 PM

To: task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Cc: Maureen327@midnet.net, Donna121@midnet.net

From: bert_task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Subject: Camino Report #2

Dear Fellow Task Force Members,

In the seven days since my last note I have learned many things. For one, when you spend your days walking, weather is really important. And for another, when you walk downhill for a long time, your toes get sore. Who knew? Fortunately, we have had several sunny days and no all-day rainy ones. The trail was much harder those first few days when it was muddy from rain the week before we arrived here and much more hilly than we expected. Now it has flattened and having the sun shine most of the time is as good for the spirits as it is for the trail underfoot.

We’re in the town of Navarette. To satisfy your curiosity, I’ll touch on some of the highlights of the past days.

Not long after leaving Pamplona we joined a Roman road, which was still more or less serviceable after apparently having not been maintained for the past 1,500 years or so. We walked over a bridge that Caesar Augustus crossed in 27 B.C. on his way to the Cantabrian wars.

One of the mornings we stopped at a roadside water station. They are common here and useful for stocking up on potable water along the way. This one was different—unique in fact—because there were two spigots and they were on the outside wall of a bodega—a large winery. The second spigot was dispensing free wine to walkers. Unfortunately it was still quite early and, tempting as it was, we resisted the urge to drain out our water bottles and refill them with wine. Too bad more places like that haven’t shown up.

The countryside has been hilly with some low mountains, which can be remarkably challenging when the ascent and descent are steep. The more moderate hills are covered with fields of grain. The scenery is not spectacular, but consistently nice with wild poppies often lining the trail. At one point we came upon an incongruity in the form of a Kraft Foods factory. We couldn’t tell what it was producing, but it probably wasn’t cheese, and must have had something to do with grain because no dairying is evident in this part of the country.

Shortly before Logroño there was a natural area that featured a restored wetland and nice storyboards about the birds and other wildlife that are benefiting from it. A short distance down the trail another sign announced that witchcraft was common in the area in the sixteenth century, and the field that was flooded to form the lake was famous as a gathering place for witches.

We entered Logroño and simultaneously the La Rioja district, famous worldwide for production of top-quality and well-regarded wines. We had a nice long day there because the walk from the monastery where we stayed (more about that below) was only about six miles. We were ready for a partial rest day and there is much to see there, including a Gothic cathedral built on a Romanesque base. We strolled the plazas and looked at the shops. Since there are good train and bus connections to Logroño, we could have bailed out and headed for the beach for the rest of the time. But gluttons for punishment, we decided neither of us was ready to bail just yet. I surprised myself by deciding to keep going. I was happy that my walking companion wanted to stick with it too. In those first few jet-lagged days I felt that she was disappointed in this grand plan she concocted. I guess she is back to normal now.

A little more about the night before last. We had a quite remarkable monastery experience. Helen had found a little-known monastery not far from town and we decided to give it a try. Unlike the monastery in Roncesvalles, this one was a trip back to the Middle Ages, replete with an antique nun questioning marital status of guests. The monastery also provided an intriguing pilgrim blessing by the whole congregation of nuns, who ranged in age from about 85 to 95 with the exception of one about 30 or more years their junior. I decided she is going to be the last nun standing and own the whole place in a few years.

When we left the city, we followed a long pedestrian way through a park. There were miles of hiking-cycling trail with no cars, trucks, buses, or motorcycles. Not that bicycles aren’t serious hazards to pedestrians, but at least they are less noisy than cars. Men and boys here are into cycling. Very few women and girls do it. The trail took us to a lake where many were fishing and picnicking. Lots of cars there, but luckily they did not share our route. They were also giving hot-air balloon rides at the park. We kept our feet on the ground.

Soon after the park we were out of the city. I was grateful to the city fathers (mothers?) for giving us that lovely walk instead of making us walk through suburban streets for hours.

The landscape that had been dominated by wheat fields before Logroño was transformed into one dominated by vineyards. The walking was pleasant, although despite all my training and preparation, by the end of a day’s walk my feet are very sore. My pack fits well, but the extra weight has made itself known by the stress it has put on my knees. The walking poles help a lot, but my left knee in particular feels as if it could give out on me at any time. Until that happens, I’ll keep on.

As you can tell from the above, a few nice experiences have tended to balance the hardships somewhat. I’m hoping for more highlights in the days to come, and to overcome my persistent physical infirmities. I would not yet recommend this vacation to a friend, so stay tuned and I’ll let you know after I’ve had more time to adapt. I can say that walking 500 miles probably isn’t for everyone, so if cruise ships appeal to you, don’t even think about this.

I appreciate your not bothering me with phone calls, Team, but I am continuing to monitor all the e-mails on my Blackberry, and I’ll be available whenever needed. I did like Ted’s suggestion about the filtering protocol and have a few more thoughts to share whenever he has time to listen to them.

Still walking,

Bert

PS. The Maureen and Donna who are copied on this message are Helen’s sisters. Helen asked me to include them since my description is so perfect she couldn’t tell our story any better. I trust that using my government e-mail account for these essentially personal messages isn’t a breach of the rules. If it is, I will leave it to one of you or somebody in the IT office to let me know. How’s that for a proactive c.y.a.?

___________

Sunday, May 22 6:12 PM

To: Maureen327@midnet.net, Donna121@midnet.net

From: Helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Not quite perfect

Maureen and Donna,

Bert really did write a great description of our journey so far, not that it was as perfect as he thinks. I would second everything he wrote about the trail and the monastery. On the other hand, I can’t imagine what made him think I was so discouraged those first few days. At any rate, wrong though he was about that, he is right that we are both feeling stronger and finding the walking less difficult. We are off now to meet some hiker friends for dinner, an Australian biology professor and a couple from England.

Helen the hiker

__________

Sunday, May 22 6:26 PM

To: Dan@northpinerefuge.gov

From: Helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Checking In

Dan,

Now that you have the gang up off their duffs, I am sure all is going well under your leadership. I appreciate your willingness to take over while I am away. I am able to check e-mail every few days, and if you need something, I will respond as quickly as possible. The hike is going well. We have covered about a hundred miles so far. Funny that it takes a whole day to go as far as you could drive in half an hour, but you certainly see a lot more on foot. We might even know what birds we were looking at if we had an identification guide. You know . . . all those little brown birds you see out the window when driving sixty miles per hour.

Helen

Regrets

Navarette to Najera

Monday, May 23

The ten-mile walk from Navarette to Nájera had been along a flat, wide clay trail that varied in color from yellow to red, with vineyards on both sides and a full open sky. The morning smiled sunshine and poppies. Almost perfect, thought Helen; a relatively short distance, beautiful weather, blue sky populated with occasional white clouds, and the promise of great local wine upon arrival.

"Wow, you can see for miles," said Bert. "I wonder if you can see all the way to that iron cross."

"You keep bringing up the Cruz de Ferro as if you expect it to be a really big deal. I hope you aren't disappointed when we finally get there."

__________

Now it was early afternoon and they were off to explore Nájera after dropping their gear at their pensión on the east side of the river. They headed over a footbridge toward a café on the river’s west side. Turning left, they passed the albergue, a single-story stone building. On the front wall was a colorful, larger-than-life mural of a classic pilgrim, replete with broad-brimmed hat decorated with a scallop shell, flowing robes, and a tall walking stick topped with a gourd to hold water. The mural wasn’t enough to counter the barracks look of its squat shape and small high windows. In addition, the guidebook said the modest structure accommodated more than 90 beds. The front courtyard reminded Helen of her grade school playground, hardpan, dusty, and lacking shade. They took a shortcut through the courtyard, past the mural and several folding clothes-drying racks.

“Kinda glad we decided not to stay here,” said Helen.

Bert nodded in agreement, looking back over his shoulder at the albergue.

They went a couple of blocks uphill and followed the familiar yellow arrows to the right along a narrow street lined with old stone houses and many shops nestled against a rock outcrop. The oldest section of town seemed to be mostly between the river and the outcrop. Helen had read that Nájera was the capital of the eleventh and twelfth century Kingdom of Navarra. Having its back to that outcrop no doubt was a protection in its heyday as the capital. The town appeared to have weathered the centuries well; a thousand years later it still had a population of 7,000 and vibrant residential and shopping districts. When they reached the far end of the historic center of town, they saw that the Camino turned and climbed along a relatively gentle rise over the outcrop.

Circling back, they took one of the other little streets that paralleled the river just downhill from them. This street too teemed with active little shops housing bakeries, tiendas, watchmakers, and farmacias. They walked back down toward the river passing a broad, grassy city park lined with sidewalk cafés. Stopping at a café-bar, they shared a two-liter bottle of water and then each ordered a large beer in their daily rehydration regimen. The river was apparently a nice trout stream. Bert called her attention to a dark green rectangular sign nailed to a post in the grass between them and the water. Actually it was two pieces of a sign that had been broken in the middle and re-nailed with not quite all the original letters intact.

The two words they could read were pesca and muerte. There was a letter “S” between them and an icon below showing a flappy-tailed fish enclosed within an oblong formed by two C-shaped arrows, one around either end of him. “We each need a second beer to figure this out,” Helen decided. The second beer was all it took.

“Catch and release!” Bert guessed.

“That sounds like a Bingo,” said Helen. “The ‘S’ probably used to be ‘sin.’ Catch without killing.”

“Today was a far cry from the exhausting, discouraging walk into Zubiri our first day,” said Helen. “Any day I’ll take yellow clay path, red poppies, vineyards, cobalt blue sky, and cotton-ball white clouds. And instead of having the only restaurant closed for fumigation, here we sit, beers in hand, looking out at a beautiful trout stream. And there are happy people all around us. I’m feeling pleasantly far removed from when I had that boulder-sized stone in my boot.

“Look,” she said. “There’s Ilsa coming along the walk toward us.” They waved her over to their table, exchanged brief greetings, and decided to meet later for dinner. Ilsa said she had spotted a small restaurant and had asked what time it opened. Most places in Nájera were not open until nine in the evening, but they could eat at this place at seven thirty.

“Wonderful!” Bert said. “We’ll meet you there.”

“She’s become a regular feature of our Camino,” Bert said, when Ilsa went off to continue her tour of the town.

“I am very comfortable with her. You like her too, don’t you? Maybe it’s because she’s a biologist, do you think? Something about her feels like we’re all cut from a similar cloth. I’m glad it is not some of the other folks we’ve met, like Nosy Sore Feet Lady or Trudi and Heinrich the Friend Collectors, who keep crossing our path,” Helen said.

“Oh, I’ve been meaning to mention a guy I overheard at the next table a few days ago when you were getting the coffee. He was an awful Mr. Know-It-All from Texas, who thought he invented the Camino. He was going on and on with unsolicited advice for anyone who couldn’t escape. Very ugly American kinda guy.

“Back to Ilsa though, I never told you but when we first met her I reacted about the way you did to Nosy Sore Feet Lady.”

“In Puente la Reina?” Helen asked.

“No, I remember her from Day One or Two, somewhere between Roncesvalles and Pamplona. I was still getting my hiking legs under me and feeling off balance in my backpack—in my whole body for that matter. She came up behind me with a ‘Buen camino’ greeting and asked me something like was I having trouble with my pack. She said it was riding to the right. She might have been right, but I found it annoying, and really none of her business. I can almost laugh about it now, but at the time I preferred not to have someone reminding me that I looked off balance. I was in a bad mood. In case you didn’t notice.”

“Bad mood? Who, You? Nuh, couldn’t be. I don’t remember the part about Ilsa,” Helen said. “But I guess I’m not surprised that it would stick in your memory.”

“Another of the several surprises of the Camino for me,” Bert said, “is how comfortable it is to be in this flow of people. Everybody is doing the hike in his or her own way, and I’m thankful nobody insists that we join their group.”

Later, when the three of them were gathered at the restaurant and seated, Bert leaned across the table toward Ilsa and asked the perfectly normal question. “Why did you decide to hike the Camino?”

Helen felt awful. Bert had missed what she’d seen the night before in Navarette when they’d all had dinner together, and she hadn’t thought to tell him about it. It’s going to be like that first night in Roncesvalles when he asked that Mexican woman, she thought. He is going to feel so bad, but it’s too late now.

When tears welled in Ilsa’s silvery eyes, Bert was visibly shocked. He took a quick breath and sat up straight, moving away from her. “I don’t mean to pry. Please don’t think I expect you to answer that,” he said in a flash.

“No wait, wait,” said Ilsa. “I am not upset with you. I really want to talk about it and have not felt comfortable with anyone until now.”

Ilsa told them she had been widowed in the Gulf War when her daughters were pre-teens. Her husband was a military doctor, and after Baghdad had capitulated he was deployed as part of the Australian humanitarian mission to the Kurds called Operation Comfort. He had died in an automobile accident in northern Iraq. He was not considered a war casualty, but it was a family casualty for sure. It was after his death that she went back to school to get her degree.

Helen realized that she had noticed a sense of enterprise in Ilsa. It was part of what she liked about her, she decided.

“I made a bad choice. I thought that as a professor I’d be able to give the girls the kind of life they would have had if David had lived. But it was a hard time for them. I was gone most of the time when I could have been helping them. They fought with each other endlessly. They never got over it,” she said. “They stopped speaking to each other as teenagers and are still estranged. I don’t know what I might have done differently, but I deeply regret that I was unable to prevent this outcome. I know I am at least partly to blame.

“For years, I’ve thought that hiking the Camino might give me time to sort this out, and maybe even make things be different. And here I am.”

No one said anything for what seemed like a very long minute.

Finally, Bert raised his glass and offered a toast, “To a successful Camino!” They touched glasses and all smiled. Helen felt sure Ilsa would be a long-time friend to them. The conversation turned to plans for the next day’s walk.

As Helen and Bert were walking back across the bridge to their pensión, she told him about the night before. When they, Ilsa, and the British couple went to dinner in Navarette, the Frenchman had joined them at the last minute because his friends were too tired to eat. Bert’s side of the table was deep in English conversation about the advantages and disadvantages of albergues, pensións, hostals, and casas rurales. On Helen and Ilsa’s side, the Frenchman asked them what had made them decide to walk the Camino?”

Helen had been able to respond fairly easily. Since the question was asked so often, she had already responded in French a couple of times. She had gotten enough French vocabulary in her head by then to give an adequate reply. She said she wasn’t really sure what brought her here. She had heard that the Camino changes people’s lives in positive and almost magical ways, and who could resist that? She hoped her choice of words was adequate to convey her meaning.

When they turned to Ilsa to hear her story, her eyes had welled up. She said only that it started with an accident, smiling in contradiction to the near tears.

Helen changed the subject to talk about trees, plants, and birds she and Bert had been noting along the trail during the day. Her shared interest with Ilsa in natural history made the shift an easy one, even in French.

Of course, Bert wouldn’t have noticed the brief incident.

Helen apologized for failing to tell him about it and inadvertently putting him in tonight’s awkward situation. She had meant to tell him, but by the time they returned to the albergue, her mind was elsewhere, and she never thought about it again.

“Oh, well,” Bert replied with a shrug, “maybe she’s better off for having told someone about it. But I can’t believe I’ve put my foot in my mouth twice, and both times with widows. Maybe my awkward question was one of the surprising and unlikely gifts of the Camino for Ilsa.”

“I don’t know quite what to make of it,” Helen said, “but I feel bad that I didn’t respond to what Ilsa said. I wanted to help her, but something in me just wouldn’t let me get any more involved than we already are. I can’t think what I should have said or done. Still, it bothers me that I didn’t do more.

“Anyway, I guess I am lucky. It must be awful to carry such a big regret. I’m so lucky not to have anything that makes me so sad . . . anything. Unlike Ilsa, I can think of nothing I’d so like to go back and do differently.”

“She got me wondering about regrets too,” said Bert. “It seems like everybody must have some by our stage in life. Maybe she is just more conscious of hers than we are of ours. I hope the Camino works its magic on whatever subconscious regrets the rest of us have as well as on Ilsa’s.”

Helen mustered a half-smile but didn’t say a word. Sometimes he drives me nuts, she thought. What did he mean about being sure that both of them have regrets? Did that have something to do with not being able to help Ilsa? She had only said she wanted to be more helpful. Then he practically accused her of hiding or failing to acknowledge some big regret. He knows full well why I’m walking the Camino. He is the one who can’t figure out what he is supposed to be doing here. How could he possibly jump to the conclusion that I have some big regret?

__________

Friday, May 27 4:15 PM

To: task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Cc: Maureen327@midnet.net, Donna121@midnet.net

From: bert_task_force_alpha@doe.gov

Subject: Camino Report #3

Dear Friends,

We arrived here in Atapuerca shortly after noon and learned that we wouldn’t be able to get into our hostal until two thirty. So we had a cup of café con leche at a little café-tienda, and while there we picked up our usual afternoon fare of cheese, sausage, bread, and wine.

We did get into our room a bit before one—a good thing because there was a crowd waiting and the place filled up soon afterward. We promptly washed out our dirty clothes and hung them on the line. It’s cool and damp, but the wind is strong, and we hope they will be mostly dry by the time we take them in.

This hostal is quite nice, a two-story, very old stone building lovingly restored with wood beams exposed and plaster walls painted vivid blues, yellows, and greens. The doors to the rooms are made of thick wood planks and the doorways are shorter than in modern construction, so I find myself ducking through, although I really don’t need to. It just feels like I might bump my head.

I am using the computer in the common room, where the yellow walls are decorated with antique farm tools no doubt typical of this rural area. This computer has an unfamiliar keyboard and some of the symbols on the keys are worn off, complicating the problem of finding the right one. So if I write something stupid or that doesn’t seem to make sense, you can be sure that the computer is at fault.

As I recall, I sent my last note from Navarette. There have been no real blockbuster sights or experiences to relate in the last several days, except some of the most spectacular scenery imaginable. We’ve walked through rolling hills covered with wheat fields as far as the eye can see. And as the road winds ahead of us, we can see to where we’ll be walking an hour later. This part of Spain is called the Meseta, and the grain production is amazing. Somebody told us this area was considered the breadbasket of the Roman Empire. If true, that would mean the fields we are passing have probably been growing wheat for well over 1,000 years. How can they do that?

Now that I have scrolled back through my photos, I realize that the scenery hasn’t all been as I’ve described above. One town, Nájera, had a trout stream running through it. (The Spanish seem to be crazy for trout and it’s often a choice with our boring peregrino meals. I almost wish I liked it.) That town was nestled among sandstone cliffs and looked like a scene from New Mexico. Then today we walked along a bleak ridge mostly given to pine plantations. The guidebook indicated that it was a wild and lawless place for medieval pilgrims, and that was easy to imagine when a cool mist closed around us.

Last night we again had dinner at a communal table at our hostal. We met a woman who told us that the Meseta has a bad name among hikers. Many prefer to cover it by bus, rather than put up with the monotony. To understand this attitude, she said, one has to be here when the grain has been harvested. Then, instead of endless waves of green, one overlooks a sea of ugly stubble. She also decried the way that farming has been so industrialized. I didn’t challenge her, but suspect that these fields were never worked by small land holders. There are no ruins of farmhouses or cottages about, and historically the land was probably owned by nobles and worked by local people from the villages. The pattern seems to have remained unchanged, although the nobles have likely been replaced by corporations.

I’m feeling stronger in my walking, although it may be that I’m just getting used to the aches and pains and no longer find them to be unexpected visitors. Helen and I have been getting reacquainted, and we’ve met some interesting people. Still, now and then I feel a bit like Dorothy in the Land of Oz, and long to be back working with the good folks on the task force. Believe it or not, that’s still mostly true, despite the cruel joke you all played on me with that e-mail. Good thing I’m such a forgiving fellow.

By the way, even though you are in my fondest thoughts, and despite my kind words, don’t expect me to bring back any trinkets. Carrying one more ounce is unthinkable, and we have hundreds of miles yet to go.

Your footsore colleague,

Bert

___________

Friday, May 27 4:45 PM

To: Maureen327@midnet.net, Donna121@midnet.net

From: Helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: More on the joke

Dear Maureen and Donna,

Not much to add to Bert’s report, except that I too am finding the walking to be less difficult. And the cruel joke? They tricked him into opening an e-mail labeled “Urgent!” that they’d made up just to bring home the message that he was too chained to his Blackberry. I told him he should have left the thing at the office! Tomorrow we arrive in Burgos. We are thinking of spending an extra day there to see the city and rest our legs and feet.

Helen the hiker

"Wow, you can see for miles," said Bert. "I wonder if you can see all the way to that iron cross."

"You keep bringing up the Cruz de Ferro as if you expect it to be a really big deal. I hope you aren't disappointed when we finally get there."

__________

Now it was early afternoon and they were off to explore Nájera after dropping their gear at their pensión on the east side of the river. They headed over a footbridge toward a café on the river’s west side. Turning left, they passed the albergue, a single-story stone building. On the front wall was a colorful, larger-than-life mural of a classic pilgrim, replete with broad-brimmed hat decorated with a scallop shell, flowing robes, and a tall walking stick topped with a gourd to hold water. The mural wasn’t enough to counter the barracks look of its squat shape and small high windows. In addition, the guidebook said the modest structure accommodated more than 90 beds. The front courtyard reminded Helen of her grade school playground, hardpan, dusty, and lacking shade. They took a shortcut through the courtyard, past the mural and several folding clothes-drying racks.

“Kinda glad we decided not to stay here,” said Helen.

Bert nodded in agreement, looking back over his shoulder at the albergue.

They went a couple of blocks uphill and followed the familiar yellow arrows to the right along a narrow street lined with old stone houses and many shops nestled against a rock outcrop. The oldest section of town seemed to be mostly between the river and the outcrop. Helen had read that Nájera was the capital of the eleventh and twelfth century Kingdom of Navarra. Having its back to that outcrop no doubt was a protection in its heyday as the capital. The town appeared to have weathered the centuries well; a thousand years later it still had a population of 7,000 and vibrant residential and shopping districts. When they reached the far end of the historic center of town, they saw that the Camino turned and climbed along a relatively gentle rise over the outcrop.

Circling back, they took one of the other little streets that paralleled the river just downhill from them. This street too teemed with active little shops housing bakeries, tiendas, watchmakers, and farmacias. They walked back down toward the river passing a broad, grassy city park lined with sidewalk cafés. Stopping at a café-bar, they shared a two-liter bottle of water and then each ordered a large beer in their daily rehydration regimen. The river was apparently a nice trout stream. Bert called her attention to a dark green rectangular sign nailed to a post in the grass between them and the water. Actually it was two pieces of a sign that had been broken in the middle and re-nailed with not quite all the original letters intact.

The two words they could read were pesca and muerte. There was a letter “S” between them and an icon below showing a flappy-tailed fish enclosed within an oblong formed by two C-shaped arrows, one around either end of him. “We each need a second beer to figure this out,” Helen decided. The second beer was all it took.

“Catch and release!” Bert guessed.

“That sounds like a Bingo,” said Helen. “The ‘S’ probably used to be ‘sin.’ Catch without killing.”

“Today was a far cry from the exhausting, discouraging walk into Zubiri our first day,” said Helen. “Any day I’ll take yellow clay path, red poppies, vineyards, cobalt blue sky, and cotton-ball white clouds. And instead of having the only restaurant closed for fumigation, here we sit, beers in hand, looking out at a beautiful trout stream. And there are happy people all around us. I’m feeling pleasantly far removed from when I had that boulder-sized stone in my boot.

“Look,” she said. “There’s Ilsa coming along the walk toward us.” They waved her over to their table, exchanged brief greetings, and decided to meet later for dinner. Ilsa said she had spotted a small restaurant and had asked what time it opened. Most places in Nájera were not open until nine in the evening, but they could eat at this place at seven thirty.

“Wonderful!” Bert said. “We’ll meet you there.”

“She’s become a regular feature of our Camino,” Bert said, when Ilsa went off to continue her tour of the town.

“I am very comfortable with her. You like her too, don’t you? Maybe it’s because she’s a biologist, do you think? Something about her feels like we’re all cut from a similar cloth. I’m glad it is not some of the other folks we’ve met, like Nosy Sore Feet Lady or Trudi and Heinrich the Friend Collectors, who keep crossing our path,” Helen said.

“Oh, I’ve been meaning to mention a guy I overheard at the next table a few days ago when you were getting the coffee. He was an awful Mr. Know-It-All from Texas, who thought he invented the Camino. He was going on and on with unsolicited advice for anyone who couldn’t escape. Very ugly American kinda guy.

“Back to Ilsa though, I never told you but when we first met her I reacted about the way you did to Nosy Sore Feet Lady.”

“In Puente la Reina?” Helen asked.

“No, I remember her from Day One or Two, somewhere between Roncesvalles and Pamplona. I was still getting my hiking legs under me and feeling off balance in my backpack—in my whole body for that matter. She came up behind me with a ‘Buen camino’ greeting and asked me something like was I having trouble with my pack. She said it was riding to the right. She might have been right, but I found it annoying, and really none of her business. I can almost laugh about it now, but at the time I preferred not to have someone reminding me that I looked off balance. I was in a bad mood. In case you didn’t notice.”

“Bad mood? Who, You? Nuh, couldn’t be. I don’t remember the part about Ilsa,” Helen said. “But I guess I’m not surprised that it would stick in your memory.”

“Another of the several surprises of the Camino for me,” Bert said, “is how comfortable it is to be in this flow of people. Everybody is doing the hike in his or her own way, and I’m thankful nobody insists that we join their group.”

Later, when the three of them were gathered at the restaurant and seated, Bert leaned across the table toward Ilsa and asked the perfectly normal question. “Why did you decide to hike the Camino?”

Helen felt awful. Bert had missed what she’d seen the night before in Navarette when they’d all had dinner together, and she hadn’t thought to tell him about it. It’s going to be like that first night in Roncesvalles when he asked that Mexican woman, she thought. He is going to feel so bad, but it’s too late now.

When tears welled in Ilsa’s silvery eyes, Bert was visibly shocked. He took a quick breath and sat up straight, moving away from her. “I don’t mean to pry. Please don’t think I expect you to answer that,” he said in a flash.

“No wait, wait,” said Ilsa. “I am not upset with you. I really want to talk about it and have not felt comfortable with anyone until now.”

Ilsa told them she had been widowed in the Gulf War when her daughters were pre-teens. Her husband was a military doctor, and after Baghdad had capitulated he was deployed as part of the Australian humanitarian mission to the Kurds called Operation Comfort. He had died in an automobile accident in northern Iraq. He was not considered a war casualty, but it was a family casualty for sure. It was after his death that she went back to school to get her degree.

Helen realized that she had noticed a sense of enterprise in Ilsa. It was part of what she liked about her, she decided.