|

You can read this section of the book here on screen, or use the buttons to download it as a PDF or Word file to read on another devise. |

|

Second Wind on the Way of St. James

© 2013 by Russell J Hall and Peg Rooney Hall Published by: Lighthall Books P.O. Box 357305 Gainesville, Florida 32635-7305 http://www.lighthallbooks.com Orders: gem@lighthallbooks.com No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, either electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, except as specified by the authors. Electronic versions made available free of charge are intended for personal use, and may not be offered for sale in any form except by the authors. Excluded from copyright are the maps, which are based on the work of Manfred Zentgraf of Volkach, Germany. Like the original, our adaptations of his map remain in the public domain. Second Wind is a work of fiction. Many experiences of the authors on the Camino have inspired and informed themes of the book, but people and events depicted are products of the authors’ imaginations; any resemblance to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental. |

Episode 2

Stage 2: New Worlds to Discover

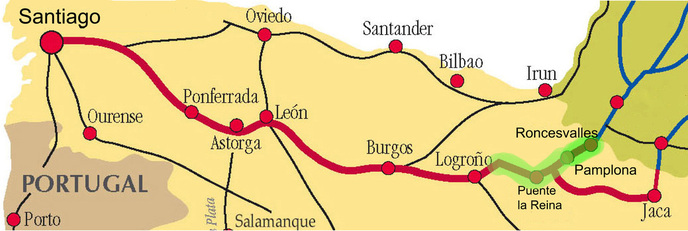

Pamplona to Logrono

The Blackberry

Pamplona to Puente la Reina

Tuesday, May 17

Even though the day before Bert had admitted that he wasn’t yet ready to give up on the Camino, a couple of big concerns nagged at him.

For the last couple of hours of each day’s walk, his legs had felt like they were made of wood, and he found this to be a disturbing development. He did not tell Helen and he hoped that before he had to tell her, the problem would have resolved itself. The first morning they had been on that not-too-difficult trail as they left Roncesvalles. In the beginning he was handling it just fine. He supposed his gait was springy, but didn’t know, because there was little reason to pay attention to it. The walking had felt natural, and he didn’t give it a thought. But soon the downhill sections were joined by the others leading upward, and he began very gradually to notice the muscles in his legs. At first it was only a feeling—he could sense a tightness developing. It wasn’t really a pain, but it was an awareness of his legs that he hadn’t noticed in the beginning. Within a couple of hours the feeling more and more resembled a pain. In fact, each step became painful, not only in his legs, but in his feet also.

Stopping to rest helped immensely. After a twenty-minute stop for coffee, the feeling of tiredness all but disappeared. He had experienced the same improvement on the second day. No surprise there—as a biologist he knew that pain in the muscles is caused by accumulation of lactic acid, and the acid begins to be converted to carbon dioxide as soon as enough oxygen can be pumped into the muscle fibers. While resting, lactic acid is no longer being produced, and more and more oxygen is reaching the cells. After each rest period, he found it difficult to stand up and to resume walking, but once underway he felt much better than he had before stopping.

He didn’t have a firm notion based on only two days’ data, but guessed that each twenty-minute stop may have gained for him forty-five minutes’ delay in the progressing soreness in his legs. The pain did eventually return, however, and as each day wore on it seemed worse than ever. Climbing hills certainly didn’t help, but after a while the downslopes felt just as bad, shifting the discomfort slightly, but in no way lessening the overall effect.

The worst of it came late in yesterday’s walk when his legs felt like they were made of wood. He was happy when Helen stopped to talk to the Nosy Sore Feet Lady so he could sit on a bench and recover without having to say anything to her about why. He wasn’t sure the wood metaphor described adequately what he felt, but what had been pains in one muscle or one part of the leg or other began to lack resolution, and each leg felt to him as if it were one large, all-encompassing pain. Almost a numbness, the sensation was nevertheless acutely painful. What concerned him most was that his wooden legs seemed to have lost much of their ability to respond to the trail and its many little hazards. Where earlier a quick adjustment or deft move on the part of the body might forestall added stress or injury, his legs had become dull and clumsy tools able to interact with their environment only in the crudest way.

What would happen today and in the days to come? Would the trail get so much easier that wooden legs wouldn’t be a problem? Would rapidly gained strength save him from repeats of the first few days’ problem—or conversely would tomorrow’s stresses pile on top of those from today and the days before? Would he learn to rest often and long enough so that sufficient oxygen was able to get to his legs? However things worked out, he knew he would need to pay attention. Whatever he had to do to keep going, somehow he would have to find a way to keep from ruining Helen’s Camino.

His problems were not all about sore legs; he had to struggle to stay in touch with his work colleagues, and Helen really seemed not to understand. Having faithfully kept his government-issued Blackberry charged and turned on, he had gotten some general information e-mails, and was thankful for being kept in the loop. Though they were not the latest in smart phones, many government agencies favored Blackberries because of their reputation as no-nonsense tools for voice and e-mail communication. But it had rung only twice since he left the United States.

The first call had come just after they boarded the bus in Pamplona for the ride to Roncesvalles. A crisis, he thought, and felt a surge of excitement as he picked up the call. But it was just Eddie the technician checking to make sure that the SIM card and changeover to the European GSM system had been executed properly.

Ironically, the second call also came in Pamplona, after they had walked in from Zubiri. They’d already fallen asleep, when the Blackberry vibrated on the nightstand between them. It didn’t wake Helen, but he did when he answered. Silly idea, he thought, that using vibrate-only would keep Helen from waking.

The call was from his colleague Kim. She must have known from his voice that she’d awakened him, even though it was only ten at night in Spain. Surprised to be talking with him, she apologized profusely.

“I must have clicked on the wrong icon,” she said. “I was trying to reach Brian and he is just below you on the list.”

“It’s all right,” he assured her. “I don’t mind. In fact, it is good to hear your voice. Guess things have been pretty quiet over there. No one has sent me any issues to deal with.”

“We’re doing fine, Bert. Maybe my errant call to you was subconscious and had something to do with how much we all enjoyed your e-mail this morning. You know what this place is like, but we haven’t been able to imagine what it is like to do what you’re doing. Now we know for sure it’s much more interesting than what we’re up to. Keep the e-mails coming! Good night.”

“Bert, what are you doing with that thing turned on in the middle of the night?” Helen said.

“I’m really sorry, Helen. I should have known it would wake us both. But I promised I would be available to the task force while I was here. So it didn’t feel right turning it off when they’re six hours behind us and even now their work day isn’t over.”

“As crazy as we both are about our jobs, I think you get the prize for being closest to obsessed,” she replied. “Let’s go back to sleep.”

Bert ignored Helen’s comment and thought about Kim’s. Maybe the team did think what he was doing is more interesting than work, but how was he to know when they weren’t sharing enough with him? Was it worth giving up his place on the task force for this? He had expected they’d keep him involved, at least to the extent he could hold up his part of their shared responsibilities.

He scanned the latest batch of their e-mails. Once again, nothing was there for him to deal with. He thought it was almost as if they were intentionally cutting him out. He switched it off.

In the morning, he awoke rested despite the nocturnal interruption. Helen didn’t bring up the Blackberry and seemed in a good mood as she dressed. He decided to put both his concerns aside for now and see what the day would bring. He thought how nice it was to watch her come out from her shower in just her underwear and blue tee-shirt she’d taken in with her and pull on her hiking pants. The rain was gone. He looked out the west-facing window at a small plaza and the Parque de la Taconera. This large, leafy park was just outside the city walls and not far from the center of the ancient city. The Camino ran through it and off into the suburbs.

He was grateful the hotel provided breakfast. They had noted in the guidebook that there were no cafés in the first few miles, so they’d decided to pick up some picnic food to carry. Helen reminded him of the advice of the Irish man who set them onto the river walk that their legs would be getting stronger by Day Three. Bert hoped he was right because they needed to cross over the Alto del Perdon, which meant they would be climbing about 1,200 feet in a three-mile stretch of the trail early today.

“Think we can take that Hill of Forgiveness?” he asked as they found their first yellow arrow painted on the sidewalk.

“It is a beautiful day, thank goodness,” she replied. “I think we’re ready for some forgiveness, and we really don’t have any choice. At least I have a better sense of what I can do without keeling over. After yesterday, I am more confident that my training wasn’t useless.”

He pushed away the wooden-legs concern that her comment conjured up.

The early miles were city walking, easy and flat but required a lot of attention to not miss a yellow arrow and thus a turn. They passed through the suburbs and the university town of Cizor Menor. The arrows were painted on pavement, lamp posts, bridge abutments, the backs of traffic signs, all over. It seemed it could be easy to miss an important one. Near the university they stopped at a church and albergue run by the Knights of Malta. The day had warmed up, and they took off their jackets. Bert felt relatively strong, so far. His pack was riding well.

Beyond the town, the trail was about ten feet wide, flat, solid, limestone color. It cut through expansive fields of grain, growing strongly from all the recent rains. The climb was gentle for a while; then the real ascent began. Ahead, the steep rise to the top of the ridge was covered with trees. Along the ridge itself, a long row of wind turbines beckoned, white-winged metal machines reaching a hundred or so feet toward the clear blue sky. He took the uphill slowly and deliberately, willing oxygen to his muscles. He appreciated the help he was getting from his walking sticks. Carrying some of his weight, they made him imagine what it would feel like to be a four-legged animal. Helen was struggling more than he with the uphill and fell behind. A cold breeze came up as they climbed. He looked forward to reaching the line of trees ahead, so they would break up the unrelenting wind.

When they stopped to rest, they both put their jackets back on. They continued climbing slowly. Where the trail went through the trees, it seemed to him they produced more chilling shade than windbreak. As they neared the ridgeline, the terrain had neither crops nor trees. It was quite barren. Bert looked back, over the cluster of trees on the steep hill they’d climbed, and could see the vastness of the valley sweeping east to Pamplona. The grinding of the turbines distracted a bit from the stress the hill put on his legs. Well, his eyes were not as miserable as his legs were, he thought. It was a spectacular vista. More than a bit out of breath, he marveled that every now and then they encountered hikers resting beside the trail, or even climbing, while smoking cigarettes.

When they got to the top, like everybody else on the trail, they collapsed onto one of the stone benches. Helen smiled at him.

“Wahoo! Look where we climbed,” she shouted over the wind and the noise of the turbines as she pointed back to Pamplona and the Pyrenees, a dim chain of peaks towering over the city. “Now I see why we were tired that first day! Look at that! You should be looking at the scenery and not at that stupid Blackberry!”

He put it away sheepishly, having taken it out while resting to see if he should respond to anything. Nothing. Following her eyes, he rejoiced again in the accomplishment of getting up here and in the beauty around them. It eased the sense that the task force was almost forcing him be a slacker.

They got coffee from a vendor selling snacks from a truck parked along a dirt road on the west side of the ridge top.

“I didn’t see that road when we were climbing up here,” Bert said. “We could have driven up to see this gorgeous view. I wonder if we’d feel the same about it. By the way, where’s the iron cross?”

“Sorry, Bert, we’re not there yet. I’ll look it up when we get in, but I bet our climb to that Cruz de Ferro will make this one seem like a bump in the road.”

As if the natural panorama around them weren’t enough, the north side of the little rest area at the crest of the Alto was adorned by life-size sculptures. They were bronze-color, cutout steel silhouettes of pilgrims in traditional garb, some riding horses, some leading donkeys, and even a dog following along.

“Every person who ever climbed this hill since the camera was invented must have a picture of these,” said Helen. “Let’s get someone to take the two of us with the sculptures.”

“I’ll do it,” said a man with flushed cheeks who got to the top just in time to overhear her, “if you’ll take mine.”

After the photo shoot, they focused for the first time on the route ahead of them. The vista was as panoramic to the west as to the east. Miles of farm fields, outlined by rows of windbreak trees, spilled over the valley spread before them from the north to the south. Looking down, they saw the sand-color trail going miles to the west, through three villages arrayed like beads on a string along the meandering line they would follow.

“Looks like we have a ways yet to go,” Bert said.

“Let’s go tackle those towns,” Helen replied. “If there really is no café-bar in that first one, like we heard, let’s stop there for our picnic lunch.”

The trail leading downhill was again about ten feet wide. It was so steep that railroad ties had been used to terrace it. It was littered with stones and rubble. Bert’s toes painfully jammed the ends of his boots with each step, and he expected that the later result would be one or more bruised and blackened toenails. More than once he kicked a loose stone, typically one about the size of a golf ball. The kick was only the prologue, however, because sometimes kicked stones came to rest just where they needed to be in order to be stepped on or kicked again. I suppose it’s possible to trip three times over the same stone, he thought, half expecting to prove his supposition before long.

The trail began to flatten at the first town. He looked back at Helen and thought something didn’t seem quite right with her.

“You okay?,” he asked.

“Maybe not,” she replied, scaring him. “I feel sort of light-headed.”

She stopped and rested against her poles. She looked too pale to him. Her hair was stuck to her face by her sweat, but he was sweating too. Her lips were almost white. It was hot now that they were down off the ridge and the wind had disappeared. She ought to look rosy.

“Bert, I need to sit and rest. This feels awful. I think I might faint.”

Luckily there was a flat rock at the side of the trail. She hobbled over and sat.

“Help me take off my pack,” she said.

He unfastened the chest strap as she undid the hip belt. He slid the pack away from her and she lay back on the rock.

“What is the matter with me?” she asked. “I felt fine and then all of a sudden I felt like this.”

“Maybe water will help,” Bert said, getting out a bottle from her pack.

She sipped slowly, raising her head just a little each time she took a sip and then leaning back on the rock and looking up at the sky. It seemed to Bert to be a long time before she looked at him again.

“I think that may be it,” she said. “All that climbing and sweating. Maybe I got dehydrated. I feel a bit better. I’m going to roll over on my side for a minute. Then I’ll see if I can sit up without feeling worse.”

“Take your time, I don’t know what to do with a fainting superwoman,” Bert said. “Don’t rush. Your color is coming back. I like you better when you don’t look like a ghost. Let’s stay here awhile and eat our picnic. Maybe food and more water will turn you back into yourself. I’m glad we brought extra water for this stretch. I’ll dig out our picnic food.”

Their guess seemed to be right. Water and food brought back her color and after another fifteen minutes or so, she seemed almost fully recovered.

“It must have been a water, or maybe blood sugar, thing,” Bert said. “You seem fine now. Do you feel as good as you look? We need to establish mandatory water breaks every hour. We should drink more than we have been.”

“You’re right. That’s a good idea. I think I feel fine again. I’m happy to sit here another few minutes to be sure. Actually, I must be back to normal because I am reminded, Bert, that your task force woke us up in the middle of the night. But now we’re over the Alto and forgiven of that, and whatever, and everything else. While we rest another minute, tell me; how did you come to be a Blackberry-carrying man?”

“Thanks for not being upset about last night, Helen. The agency issued me the Blackberry when I got the assignment to the interagency task force. After the surgery, it was going to be months before I could work full-time again and when the half-time task force position came up I jumped at it.”

“Why go part-time? You could have just taken sick-leave,” she said.

“Oh no, I couldn’t just stay out of work for all those months! I’m a scientist. I couldn’t stay away from my projects. They’re important and need someone paying attention. And, by the time I came back I’d really be out of the loop. How would I ever find a really substantive position if I just walked away like that?”

“Couldn’t you do your regular job on a part-time basis?”

“No, that wouldn’t have worked in the endangered species job. I couldn’t have managed that program properly as a part-timer. And, actually, I didn’t mind doing something different. I never felt that job was quite right for me. In some ways I’ve never felt that any of my jobs have given me the chance to do as much as I think I could.”

“Hmm, you don’t feel like you have ever had the right job, but still you didn’t want to walk away? Well, until this refuge manager job, I always felt a bit under-employed, so maybe I get what you mean,” she said.

“We’re off track. How did you get so chained to that Blackberry?”

“Ah, yes. Back to the question. Are you ready to hit the trail again?”

“Yes, I feel fine now. Let’s go on.”

They packed the remnants of the picnic and resumed walking.

“Maybe that Irish guy was right about Day Three or maybe we’re getting the hang of this, Helen. You look all cured, and the rest seems to have really worked for me, too. Ok, back to the Blackberry.”

“Yes, I still want to know!” Helen said.

“The task force’s job is to advise about the siting of the permanent nuclear waste repository everyone’s been wanting for decades. The other members are full-timers, geologists and engineers. They plug away at the data and when they need me, it is to ascertain that sites they’re considering don’t include critical habitats of endangered species, or that construction and operation of proposed facilities might damage habitats or affect federally protected wildlife species.

“With my Blackberry at the ready, they could contact me regardless of where I was. Working out on the treadmills, having my sore body stretched and massaged, whatever, I found that being able to be available exactly when needed was really great. And I always have access to the Internet and all my documents. Really, I’d hate to be without it and will have to get myself a smart phone of some kind when I turn this one in. I don’t think I could have come on the Camino and just left the team in the lurch. With the Blackberry, I’m still connected to the agency and the science.”

“Still sounds obsessive to me, Bert,” she replied. “At least I understand why you think a couple of hours a week in an Internet café wouldn’t work for you. And, since bringing it made it possible for you to come on the Camino with me, I won’t complain about it anymore.”

The conversation had carried them down the hill toward Puente la Reina. As they approached the last of the string of towns along their way, Bert saw the red light blinking on the Blackberry. Pressing the trackball, he opened the message list and saw that several had arrived. The latest one, the one on top, was titled Chilling Out? What caught his attention, however, was the one immediately below it, with the title URGENT! He clicked on it first, and got the following message:

Your colleagues (we miss you).

____________

Relieved and somewhat touched by this quirky bit of mischief, Bert opened the later note, the one at the top of the list. It said:

Please chill out and disregard the phony note with the title “URGENT!”

____________

He showed the messages to Helen. She laughed, but scolded him again, saying that he should have left his Blackberry at the office.

“Even your colleagues want you to forget work and enjoy the break from it,” she said. “Surely you didn’t miss the message in their humor.”

“Yes, I get it,” he said.

He appreciated the humor. It did not mitigate his nagging concern. What if an important scientific issue came up—one which needed his expertise? Would they consult him? The thought of them making a wrong-headed decision because he wasn’t there was disturbing. Despite Helen’s words, he liked the feeling that the Blackberry kept him connected to them.

A scene popped into his consciousness. He was sitting with his parents at the supper table. They were old for having a little kid like him. His siblings were already grown and gone. He had begun to tell them about the science project he had worked on in school that day, but neither of them looked up from the books they were reading. He wondered if he could have gotten their attention with an email to their Blackberries, which wouldn’t be invented until years after their deaths of course.

For no particular reason he remembered a long-ago conversation he’d had with Helen about each of their parents. His family was not like hers at all. They were good to him in all the important things, but mostly left him to his own devices, as if they had forgotten all the subtler responsibilities of parenthood. By the time he was an adult they were both dead. He guessed that he had never really gotten to know them very well.

Helen found his family story surprising. He remembered her saying that she thought he must have missed an important part of his life, not being connected to his parents or siblings when he was young. Nevertheless, remembering them now, they seemed to have something to do with work and his Blackberry. Maybe his subconscious wanted to send his parents an e-mail. He laughed to himself. The thought was absurd, of course, but it led him to wonder whether the Blackberry was his main connection to other people.

They arrived in Puente, found the albergue, and soon discovered that the choices for sleeping accommodations were limited.

“I’m too old to sleep in an upper bunk.”

“I am too. So what do we do about it?”

There was nothing to be done about it of course, so they’d agreed that Bert would be the first to take the upper, and Helen would take her turn the next time the situation arose. They had heard that upper and lower bunks have their respective disadvantages. Occupants of upper bunks have the athletic chore of climbing in and out of them and, of course, the fear that a tumble out of bed could have disastrous consequences. Occupants of lowers discover almost immediately that there is not enough headroom to sit up on the bunk, with the result that reading or putting on one’s shoes is a challenge. And while falling out of a lower bunk is not a great hazard, the possibility that the upper bunkmate might fall on or step on you cannot be discounted.

Also in crowded albergues the narrow aisles between beds offer too meager places to stow one’s gear, let alone organize it. Limited physical spaces, they had been told, were only the beginning of hardships likely to be encountered in crowded albergues.

The laws of probability seemed to dictate that when ten or more people are sleeping in a single room, at least one will be a snorer, one will be a light sleeper who gets up multiple times during the night, some surely will be early risers who will begin banging around before five o’clock in the morning, and one or more will want the windows open on nights when the temperature dips into the thirties. With effort, modest people could get by without indecently exposing themselves, but might find it difficult to avoid being offended by others who lacked reasonable modesty. It was not a frequent occurrence, but some pilgrims had tales of sharing quarters with persons who came in drunk and boisterous. Of course, close quarters can lead to annoyances that would simply be ignored in other circumstances.

Now they’d be able to experience first-hand what they’d only heard about.

For the last couple of hours of each day’s walk, his legs had felt like they were made of wood, and he found this to be a disturbing development. He did not tell Helen and he hoped that before he had to tell her, the problem would have resolved itself. The first morning they had been on that not-too-difficult trail as they left Roncesvalles. In the beginning he was handling it just fine. He supposed his gait was springy, but didn’t know, because there was little reason to pay attention to it. The walking had felt natural, and he didn’t give it a thought. But soon the downhill sections were joined by the others leading upward, and he began very gradually to notice the muscles in his legs. At first it was only a feeling—he could sense a tightness developing. It wasn’t really a pain, but it was an awareness of his legs that he hadn’t noticed in the beginning. Within a couple of hours the feeling more and more resembled a pain. In fact, each step became painful, not only in his legs, but in his feet also.

Stopping to rest helped immensely. After a twenty-minute stop for coffee, the feeling of tiredness all but disappeared. He had experienced the same improvement on the second day. No surprise there—as a biologist he knew that pain in the muscles is caused by accumulation of lactic acid, and the acid begins to be converted to carbon dioxide as soon as enough oxygen can be pumped into the muscle fibers. While resting, lactic acid is no longer being produced, and more and more oxygen is reaching the cells. After each rest period, he found it difficult to stand up and to resume walking, but once underway he felt much better than he had before stopping.

He didn’t have a firm notion based on only two days’ data, but guessed that each twenty-minute stop may have gained for him forty-five minutes’ delay in the progressing soreness in his legs. The pain did eventually return, however, and as each day wore on it seemed worse than ever. Climbing hills certainly didn’t help, but after a while the downslopes felt just as bad, shifting the discomfort slightly, but in no way lessening the overall effect.

The worst of it came late in yesterday’s walk when his legs felt like they were made of wood. He was happy when Helen stopped to talk to the Nosy Sore Feet Lady so he could sit on a bench and recover without having to say anything to her about why. He wasn’t sure the wood metaphor described adequately what he felt, but what had been pains in one muscle or one part of the leg or other began to lack resolution, and each leg felt to him as if it were one large, all-encompassing pain. Almost a numbness, the sensation was nevertheless acutely painful. What concerned him most was that his wooden legs seemed to have lost much of their ability to respond to the trail and its many little hazards. Where earlier a quick adjustment or deft move on the part of the body might forestall added stress or injury, his legs had become dull and clumsy tools able to interact with their environment only in the crudest way.

What would happen today and in the days to come? Would the trail get so much easier that wooden legs wouldn’t be a problem? Would rapidly gained strength save him from repeats of the first few days’ problem—or conversely would tomorrow’s stresses pile on top of those from today and the days before? Would he learn to rest often and long enough so that sufficient oxygen was able to get to his legs? However things worked out, he knew he would need to pay attention. Whatever he had to do to keep going, somehow he would have to find a way to keep from ruining Helen’s Camino.

His problems were not all about sore legs; he had to struggle to stay in touch with his work colleagues, and Helen really seemed not to understand. Having faithfully kept his government-issued Blackberry charged and turned on, he had gotten some general information e-mails, and was thankful for being kept in the loop. Though they were not the latest in smart phones, many government agencies favored Blackberries because of their reputation as no-nonsense tools for voice and e-mail communication. But it had rung only twice since he left the United States.

The first call had come just after they boarded the bus in Pamplona for the ride to Roncesvalles. A crisis, he thought, and felt a surge of excitement as he picked up the call. But it was just Eddie the technician checking to make sure that the SIM card and changeover to the European GSM system had been executed properly.

Ironically, the second call also came in Pamplona, after they had walked in from Zubiri. They’d already fallen asleep, when the Blackberry vibrated on the nightstand between them. It didn’t wake Helen, but he did when he answered. Silly idea, he thought, that using vibrate-only would keep Helen from waking.

The call was from his colleague Kim. She must have known from his voice that she’d awakened him, even though it was only ten at night in Spain. Surprised to be talking with him, she apologized profusely.

“I must have clicked on the wrong icon,” she said. “I was trying to reach Brian and he is just below you on the list.”

“It’s all right,” he assured her. “I don’t mind. In fact, it is good to hear your voice. Guess things have been pretty quiet over there. No one has sent me any issues to deal with.”

“We’re doing fine, Bert. Maybe my errant call to you was subconscious and had something to do with how much we all enjoyed your e-mail this morning. You know what this place is like, but we haven’t been able to imagine what it is like to do what you’re doing. Now we know for sure it’s much more interesting than what we’re up to. Keep the e-mails coming! Good night.”

“Bert, what are you doing with that thing turned on in the middle of the night?” Helen said.

“I’m really sorry, Helen. I should have known it would wake us both. But I promised I would be available to the task force while I was here. So it didn’t feel right turning it off when they’re six hours behind us and even now their work day isn’t over.”

“As crazy as we both are about our jobs, I think you get the prize for being closest to obsessed,” she replied. “Let’s go back to sleep.”

Bert ignored Helen’s comment and thought about Kim’s. Maybe the team did think what he was doing is more interesting than work, but how was he to know when they weren’t sharing enough with him? Was it worth giving up his place on the task force for this? He had expected they’d keep him involved, at least to the extent he could hold up his part of their shared responsibilities.

He scanned the latest batch of their e-mails. Once again, nothing was there for him to deal with. He thought it was almost as if they were intentionally cutting him out. He switched it off.

In the morning, he awoke rested despite the nocturnal interruption. Helen didn’t bring up the Blackberry and seemed in a good mood as she dressed. He decided to put both his concerns aside for now and see what the day would bring. He thought how nice it was to watch her come out from her shower in just her underwear and blue tee-shirt she’d taken in with her and pull on her hiking pants. The rain was gone. He looked out the west-facing window at a small plaza and the Parque de la Taconera. This large, leafy park was just outside the city walls and not far from the center of the ancient city. The Camino ran through it and off into the suburbs.

He was grateful the hotel provided breakfast. They had noted in the guidebook that there were no cafés in the first few miles, so they’d decided to pick up some picnic food to carry. Helen reminded him of the advice of the Irish man who set them onto the river walk that their legs would be getting stronger by Day Three. Bert hoped he was right because they needed to cross over the Alto del Perdon, which meant they would be climbing about 1,200 feet in a three-mile stretch of the trail early today.

“Think we can take that Hill of Forgiveness?” he asked as they found their first yellow arrow painted on the sidewalk.

“It is a beautiful day, thank goodness,” she replied. “I think we’re ready for some forgiveness, and we really don’t have any choice. At least I have a better sense of what I can do without keeling over. After yesterday, I am more confident that my training wasn’t useless.”

He pushed away the wooden-legs concern that her comment conjured up.

The early miles were city walking, easy and flat but required a lot of attention to not miss a yellow arrow and thus a turn. They passed through the suburbs and the university town of Cizor Menor. The arrows were painted on pavement, lamp posts, bridge abutments, the backs of traffic signs, all over. It seemed it could be easy to miss an important one. Near the university they stopped at a church and albergue run by the Knights of Malta. The day had warmed up, and they took off their jackets. Bert felt relatively strong, so far. His pack was riding well.

Beyond the town, the trail was about ten feet wide, flat, solid, limestone color. It cut through expansive fields of grain, growing strongly from all the recent rains. The climb was gentle for a while; then the real ascent began. Ahead, the steep rise to the top of the ridge was covered with trees. Along the ridge itself, a long row of wind turbines beckoned, white-winged metal machines reaching a hundred or so feet toward the clear blue sky. He took the uphill slowly and deliberately, willing oxygen to his muscles. He appreciated the help he was getting from his walking sticks. Carrying some of his weight, they made him imagine what it would feel like to be a four-legged animal. Helen was struggling more than he with the uphill and fell behind. A cold breeze came up as they climbed. He looked forward to reaching the line of trees ahead, so they would break up the unrelenting wind.

When they stopped to rest, they both put their jackets back on. They continued climbing slowly. Where the trail went through the trees, it seemed to him they produced more chilling shade than windbreak. As they neared the ridgeline, the terrain had neither crops nor trees. It was quite barren. Bert looked back, over the cluster of trees on the steep hill they’d climbed, and could see the vastness of the valley sweeping east to Pamplona. The grinding of the turbines distracted a bit from the stress the hill put on his legs. Well, his eyes were not as miserable as his legs were, he thought. It was a spectacular vista. More than a bit out of breath, he marveled that every now and then they encountered hikers resting beside the trail, or even climbing, while smoking cigarettes.

When they got to the top, like everybody else on the trail, they collapsed onto one of the stone benches. Helen smiled at him.

“Wahoo! Look where we climbed,” she shouted over the wind and the noise of the turbines as she pointed back to Pamplona and the Pyrenees, a dim chain of peaks towering over the city. “Now I see why we were tired that first day! Look at that! You should be looking at the scenery and not at that stupid Blackberry!”

He put it away sheepishly, having taken it out while resting to see if he should respond to anything. Nothing. Following her eyes, he rejoiced again in the accomplishment of getting up here and in the beauty around them. It eased the sense that the task force was almost forcing him be a slacker.

They got coffee from a vendor selling snacks from a truck parked along a dirt road on the west side of the ridge top.

“I didn’t see that road when we were climbing up here,” Bert said. “We could have driven up to see this gorgeous view. I wonder if we’d feel the same about it. By the way, where’s the iron cross?”

“Sorry, Bert, we’re not there yet. I’ll look it up when we get in, but I bet our climb to that Cruz de Ferro will make this one seem like a bump in the road.”

As if the natural panorama around them weren’t enough, the north side of the little rest area at the crest of the Alto was adorned by life-size sculptures. They were bronze-color, cutout steel silhouettes of pilgrims in traditional garb, some riding horses, some leading donkeys, and even a dog following along.

“Every person who ever climbed this hill since the camera was invented must have a picture of these,” said Helen. “Let’s get someone to take the two of us with the sculptures.”

“I’ll do it,” said a man with flushed cheeks who got to the top just in time to overhear her, “if you’ll take mine.”

After the photo shoot, they focused for the first time on the route ahead of them. The vista was as panoramic to the west as to the east. Miles of farm fields, outlined by rows of windbreak trees, spilled over the valley spread before them from the north to the south. Looking down, they saw the sand-color trail going miles to the west, through three villages arrayed like beads on a string along the meandering line they would follow.

“Looks like we have a ways yet to go,” Bert said.

“Let’s go tackle those towns,” Helen replied. “If there really is no café-bar in that first one, like we heard, let’s stop there for our picnic lunch.”

The trail leading downhill was again about ten feet wide. It was so steep that railroad ties had been used to terrace it. It was littered with stones and rubble. Bert’s toes painfully jammed the ends of his boots with each step, and he expected that the later result would be one or more bruised and blackened toenails. More than once he kicked a loose stone, typically one about the size of a golf ball. The kick was only the prologue, however, because sometimes kicked stones came to rest just where they needed to be in order to be stepped on or kicked again. I suppose it’s possible to trip three times over the same stone, he thought, half expecting to prove his supposition before long.

The trail began to flatten at the first town. He looked back at Helen and thought something didn’t seem quite right with her.

“You okay?,” he asked.

“Maybe not,” she replied, scaring him. “I feel sort of light-headed.”

She stopped and rested against her poles. She looked too pale to him. Her hair was stuck to her face by her sweat, but he was sweating too. Her lips were almost white. It was hot now that they were down off the ridge and the wind had disappeared. She ought to look rosy.

“Bert, I need to sit and rest. This feels awful. I think I might faint.”

Luckily there was a flat rock at the side of the trail. She hobbled over and sat.

“Help me take off my pack,” she said.

He unfastened the chest strap as she undid the hip belt. He slid the pack away from her and she lay back on the rock.

“What is the matter with me?” she asked. “I felt fine and then all of a sudden I felt like this.”

“Maybe water will help,” Bert said, getting out a bottle from her pack.

She sipped slowly, raising her head just a little each time she took a sip and then leaning back on the rock and looking up at the sky. It seemed to Bert to be a long time before she looked at him again.

“I think that may be it,” she said. “All that climbing and sweating. Maybe I got dehydrated. I feel a bit better. I’m going to roll over on my side for a minute. Then I’ll see if I can sit up without feeling worse.”

“Take your time, I don’t know what to do with a fainting superwoman,” Bert said. “Don’t rush. Your color is coming back. I like you better when you don’t look like a ghost. Let’s stay here awhile and eat our picnic. Maybe food and more water will turn you back into yourself. I’m glad we brought extra water for this stretch. I’ll dig out our picnic food.”

Their guess seemed to be right. Water and food brought back her color and after another fifteen minutes or so, she seemed almost fully recovered.

“It must have been a water, or maybe blood sugar, thing,” Bert said. “You seem fine now. Do you feel as good as you look? We need to establish mandatory water breaks every hour. We should drink more than we have been.”

“You’re right. That’s a good idea. I think I feel fine again. I’m happy to sit here another few minutes to be sure. Actually, I must be back to normal because I am reminded, Bert, that your task force woke us up in the middle of the night. But now we’re over the Alto and forgiven of that, and whatever, and everything else. While we rest another minute, tell me; how did you come to be a Blackberry-carrying man?”

“Thanks for not being upset about last night, Helen. The agency issued me the Blackberry when I got the assignment to the interagency task force. After the surgery, it was going to be months before I could work full-time again and when the half-time task force position came up I jumped at it.”

“Why go part-time? You could have just taken sick-leave,” she said.

“Oh no, I couldn’t just stay out of work for all those months! I’m a scientist. I couldn’t stay away from my projects. They’re important and need someone paying attention. And, by the time I came back I’d really be out of the loop. How would I ever find a really substantive position if I just walked away like that?”

“Couldn’t you do your regular job on a part-time basis?”

“No, that wouldn’t have worked in the endangered species job. I couldn’t have managed that program properly as a part-timer. And, actually, I didn’t mind doing something different. I never felt that job was quite right for me. In some ways I’ve never felt that any of my jobs have given me the chance to do as much as I think I could.”

“Hmm, you don’t feel like you have ever had the right job, but still you didn’t want to walk away? Well, until this refuge manager job, I always felt a bit under-employed, so maybe I get what you mean,” she said.

“We’re off track. How did you get so chained to that Blackberry?”

“Ah, yes. Back to the question. Are you ready to hit the trail again?”

“Yes, I feel fine now. Let’s go on.”

They packed the remnants of the picnic and resumed walking.

“Maybe that Irish guy was right about Day Three or maybe we’re getting the hang of this, Helen. You look all cured, and the rest seems to have really worked for me, too. Ok, back to the Blackberry.”

“Yes, I still want to know!” Helen said.

“The task force’s job is to advise about the siting of the permanent nuclear waste repository everyone’s been wanting for decades. The other members are full-timers, geologists and engineers. They plug away at the data and when they need me, it is to ascertain that sites they’re considering don’t include critical habitats of endangered species, or that construction and operation of proposed facilities might damage habitats or affect federally protected wildlife species.

“With my Blackberry at the ready, they could contact me regardless of where I was. Working out on the treadmills, having my sore body stretched and massaged, whatever, I found that being able to be available exactly when needed was really great. And I always have access to the Internet and all my documents. Really, I’d hate to be without it and will have to get myself a smart phone of some kind when I turn this one in. I don’t think I could have come on the Camino and just left the team in the lurch. With the Blackberry, I’m still connected to the agency and the science.”

“Still sounds obsessive to me, Bert,” she replied. “At least I understand why you think a couple of hours a week in an Internet café wouldn’t work for you. And, since bringing it made it possible for you to come on the Camino with me, I won’t complain about it anymore.”

The conversation had carried them down the hill toward Puente la Reina. As they approached the last of the string of towns along their way, Bert saw the red light blinking on the Blackberry. Pressing the trackball, he opened the message list and saw that several had arrived. The latest one, the one on top, was titled Chilling Out? What caught his attention, however, was the one immediately below it, with the title URGENT! He clicked on it first, and got the following message:

- Urgent! All task force members are to report to room 42A in the Sanders Building no later than 9 AM on Thursday May 19 for an urgent meeting to discuss an item of major and immediate importance.

- All leave is herewith cancelled, and persons presently on leave are to return to the Washington area and report to duty stations as soon as possible. Sick leave is likewise cancelled except in cases where reporting for work would pose an immediate threat to life.

- Several task force members have taken actions from which there is no retreat and no remediation, and the fallout may compromise the integrity of our mission.

- Data that were to be provided by a consortium of several state governments have not arrived in the expected time frame, and this has left the task force for several days with no meaningful work to do.

- Faced with idleness and boredom, task force members conspired to compose and send this bogus note to their valued colleague Bert Charles.

- They sent a later note and then engaged in wagering which note he would open first, some betting that he would have chilled out enough to open the later one, and others betting that he couldn’t resist the call of the “URGENT!” one.

- Hey, Bert, if you haven’t chilled out yet, we hope this will help you to do so.

Your colleagues (we miss you).

____________

Relieved and somewhat touched by this quirky bit of mischief, Bert opened the later note, the one at the top of the list. It said:

Please chill out and disregard the phony note with the title “URGENT!”

____________

He showed the messages to Helen. She laughed, but scolded him again, saying that he should have left his Blackberry at the office.

“Even your colleagues want you to forget work and enjoy the break from it,” she said. “Surely you didn’t miss the message in their humor.”

“Yes, I get it,” he said.

He appreciated the humor. It did not mitigate his nagging concern. What if an important scientific issue came up—one which needed his expertise? Would they consult him? The thought of them making a wrong-headed decision because he wasn’t there was disturbing. Despite Helen’s words, he liked the feeling that the Blackberry kept him connected to them.

A scene popped into his consciousness. He was sitting with his parents at the supper table. They were old for having a little kid like him. His siblings were already grown and gone. He had begun to tell them about the science project he had worked on in school that day, but neither of them looked up from the books they were reading. He wondered if he could have gotten their attention with an email to their Blackberries, which wouldn’t be invented until years after their deaths of course.

For no particular reason he remembered a long-ago conversation he’d had with Helen about each of their parents. His family was not like hers at all. They were good to him in all the important things, but mostly left him to his own devices, as if they had forgotten all the subtler responsibilities of parenthood. By the time he was an adult they were both dead. He guessed that he had never really gotten to know them very well.

Helen found his family story surprising. He remembered her saying that she thought he must have missed an important part of his life, not being connected to his parents or siblings when he was young. Nevertheless, remembering them now, they seemed to have something to do with work and his Blackberry. Maybe his subconscious wanted to send his parents an e-mail. He laughed to himself. The thought was absurd, of course, but it led him to wonder whether the Blackberry was his main connection to other people.

They arrived in Puente, found the albergue, and soon discovered that the choices for sleeping accommodations were limited.

“I’m too old to sleep in an upper bunk.”

“I am too. So what do we do about it?”

There was nothing to be done about it of course, so they’d agreed that Bert would be the first to take the upper, and Helen would take her turn the next time the situation arose. They had heard that upper and lower bunks have their respective disadvantages. Occupants of upper bunks have the athletic chore of climbing in and out of them and, of course, the fear that a tumble out of bed could have disastrous consequences. Occupants of lowers discover almost immediately that there is not enough headroom to sit up on the bunk, with the result that reading or putting on one’s shoes is a challenge. And while falling out of a lower bunk is not a great hazard, the possibility that the upper bunkmate might fall on or step on you cannot be discounted.

Also in crowded albergues the narrow aisles between beds offer too meager places to stow one’s gear, let alone organize it. Limited physical spaces, they had been told, were only the beginning of hardships likely to be encountered in crowded albergues.

The laws of probability seemed to dictate that when ten or more people are sleeping in a single room, at least one will be a snorer, one will be a light sleeper who gets up multiple times during the night, some surely will be early risers who will begin banging around before five o’clock in the morning, and one or more will want the windows open on nights when the temperature dips into the thirties. With effort, modest people could get by without indecently exposing themselves, but might find it difficult to avoid being offended by others who lacked reasonable modesty. It was not a frequent occurrence, but some pilgrims had tales of sharing quarters with persons who came in drunk and boisterous. Of course, close quarters can lead to annoyances that would simply be ignored in other circumstances.

Now they’d be able to experience first-hand what they’d only heard about.

Bridges

Puente la Reina to Estella

Wednesday, May 18

After a night that seemed to offer a complete tableau of all the undesired experiences an albergue can offer up, Helen and Bert found that they were both surprisingly upbeat.

“Despite everything, that was kind of fun,” said bleary-eyed Bert. “I didn’t come to Spain to sleep, so I guess I can’t claim to have been cheated.”

“Yeah, it wasn’t dull, and we have tales we can tell our friends. Plus we’ll have something to talk about if we bump into any of our bunkhouse fellows again. We’ll make some remark about how awful it was, and we’ll all have a good laugh together.”

“Wow! I have something in common with thirty people from the four corners of the earth! A bad night’s sleep! Ultreia!”

“I keep seeing and hearing that word,” said Helen. “Have you figured out what it means, exactly? It’s not in my dictionary.”

“Not really. But I think something like ‘onward’ or ‘keep it up’ is a good guess,” he replied. ”That fits the context of where I’ve seen it.”

“Good guess,” she said.

Helen indeed felt good as they left their Puente la Reina albergue and headed off on their way to Estella. They seemed to have left all rain behind. It was a sunny, cool morning. No jacket needed, just her tee-shirt with the long-sleeved shirt over it until it warmed up a bit. They walked down the narrow streets of the old town with Ilsa, who they’d met at the albergue. Coming up behind her, they recognized her at once by her long ponytail, blond and streaked with gray. She gave the same gold-and-silver impression from the front, with her fringe of blond hair and shining silver-gray eyes.

The twenty bunk beds in their basement room in the albergue had actually offered a tad of privacy because the beds were tucked into little cubicles. Ilsa was in the cubicle next to Bert and Helen. They all arrived at about the same time and went down into the dormitory together. Later they spotted her outside in the café-bar and asked if they could join her.

“I saw, when we all registered, that you’re from Australia,” Helen had said, sensing a companionable interlude. “It taxes my imagination to believe anyone comes all the way from Australia to hike the Camino!”

“Australia is so far from everywhere that many Australians, like me, prefer to get away on travel now and again. When you come to Europe, you do really want to stay a while. Walking the Camino is appealing because it isn’t being a tourist, it isn’t expensive, and it gives you time to think. I’m on winter break and walking by myself. I longed for some time to be really on my own, away from everything,” she said.

They had much in common and had spent a nice hour or so comparing career notes after they learned she taught zoology in Perth and she learned they were wildlife biologists. She hadn’t joined them at dinner but an interesting German couple did, and Helen enjoyed their company too.

Leaving Puente la Reina, the three of them crossed the namesake structure, a six-arch bridge built in the eleventh century to help pilgrims cross the Arga River. They each took photographs of the bridge and each other standing on it. Apparently preferring to walk alone, Ilsa bid them buen camino and headed off ahead on her own.

The countryside had a rugged aspect, but the trail was in very good shape—a wide clay path far from roads and traffic—and the walking was relatively easy. Vineyards and small wheat fields were tucked into the gentler slopes between the hills. The landscape was flooded with bright sunlight that gave it an almost luminescent quality.

Bert said he felt his body was, maybe, less resistant to the walking than it had been on the first two days. All wasn’t good, of course, and he went on to say something about a knee that wasn’t quite right and a sore back that he attributed to the sagging bunk in the albergue. Helen found herself still fussing with her pack, but only from time to time. It was riding better than on that hard first day. Another positive note was that her boots had mostly dried out, having been through stages of wetness, dampness, and near-dryness since the dunking they had taken on the way to Pamplona. They stopped in Mañeru for a rest and large cups of strong coffee, this time taken sin leche. This was not going to be a short day—nearly fourteen miles. Helen was inclined to stop and rest whenever the opportunity presented itself. Maybe resting often would be a way they could do this Camino after all, she thought.

A few miles beyond Mañeru they were overtaken and found themselves walking for a pleasant twenty minutes with the German couple they’d met at dinner the night before. Their names were Peter and Margot. They were walking alone, together, all the way from their home in Germany. Helen was pleased and realized she had begun to assemble her own little group of casual Camino friends. The thought that she and Bert might turn into the Friend Collectors Trudi and Heinrich was so absurd, it made her laugh to herself.

The conversation turned to rain gear. Peter remarked that their backpacks were still damp more than a day after they had experienced a torrential downpour approaching Zubiri. Finding no available lodging, they had been forced to walk on. They had worn waterproof jackets and put water repellant covers over their backpacks, but the driving rain had soaked the uncovered parts of their packs, including the shoulder straps and waist belt. Almost worse, it had dampened the inside of their packs—the parts that rested against their backs; water had cascaded off their hats and shoulders and invaded these spaces.

“We were lucky in two ways,” Bert said. “First, we had already settled into our hostal when the storm struck, and second, I received good advice about rain protection from the young man who sold me my pack. He said that most backpacks are not waterproof, and that he would gladly sell me a pack cover. He warned me about just what happened to you. He told me that the shower cap-like cover would protect only the back part of the pack, and the other parts, including the padded straps and waist belts would be vulnerable. Then he said he would happily sell me a slicker-like rain cape. A bit more expensive, it would cover pack and hiker, and provide unmatched protection from the rain.

“He went on to tell me of all the complaints he heard. Not only was the rain cape heavy, but its inside might frequently resemble a steam bath. It breathes poorly, and wearers often found themselves as wet as if they had no rain protection at all. His advice was to purchase a waterproof rain poncho, either a specialized one with a built-in hump for a backpack, or an inexpensive regular poncho. The less expensive one would cover the pack and upper body all right, but might not fully protect the back of one’s pant legs. Either one would avoid the steam-bath phenomenon by allowing air to circulate underneath. We haven’t tested our twenty-dollar ponchos in a really heavy thunderstorm, but they have worked well so far in light to moderate rainstorms, and are far lighter than rain capes.”

“You sure are a scientist,” remarked Peter. “All that analysis and inference; I couldn’t stand it. Oh, I would be happier right now if I wasn’t damp, but we prefer to go where the road takes us and deal with whatever nature serves up to us. I guess we told you that we began our Camino several years ago by walking out our front door. I think we locked it behind us, but I really don’t remember.”

Noting a look of chagrin on Bert’s face, Helen promptly changed the subject, remarking on the wildflowers along the trail.

The light chatter continued among the four of them until Peter and Margot decided to stop in Cirauqui. Bert said he wasn’t ready to stop again, but looked to Helen, since she’d suggested frequent breaks on this long day. She agreed that they should go on. It had been only a few miles since Mañeru.

“Will we see you again?” Helen asked at parting. The answer was equivocal. Peter had suffered an ankle injury, and would be deciding on a daily basis whether and how far they would be walking. They had no expectation of reaching Santiago this year. They had indeed walked out their front door in Germany several summers ago and walked for three weeks until it was time to go back to work. Each subsequent summer, they took a bus to where they had stopped the previous year and started again. Within the next week, they would catch a train or bus and return home. Maybe next year, they’d reach Santiago. The possibility of meeting again was a definite “maybe.” Just in case they didn’t, they exchanged e-mail addresses before their farewells.

On the far side of Cirauqui the trail followed the remains of an old Roman road and crossed a relatively well-preserved Roman bridge.

“Time for another bridge photo,” said Helen, and each photographed the other standing on the bridge. She had read that this very bridge was crossed by Caesar Augustus in 27 A.D., during the Cantabrian wars.

“Cool, but I’m disappointed in the road,” Bert said. “When we learned about Roman roads in Latin class, the diagram in the book showed them as having smooth surfaces. The edges on this one are smooth, but most of the roadbed is just filled with this rubble. I can feel the stones even through the Vibram soles of my boots. I can imagine that a Roman wearing leather sandals would feel them much more.”

“Maybe they packed gravel or soil around the stones to make it smooth. It’s easy to believe it could have managed to wash away in a couple of thousand years’ worth of rains,” she suggested.

A few kilometers further along the path they came to another notable bridge, this a two-arched medieval one with a heavily buttressed central pillar to deflect flood-borne debris. They took more photographs. Bert commented that building practices seemed to have improved in 1,000 years; although the surface of this bridge was paved with rough-cut cobblestones, it was far smoother than the Roman road.

Birds called around them, although they saw few, and recognized only one. That one—not seen, but often heard—would greet them with a loud “cu—koo.”

“Even the wildlife have developed an opinion on what mental condition led us to the Camino,” Bert said.

They were coming up behind another walker.

“Hello,” she said as they drew abreast. They slowed to match her pace.

The short, strongly built, woman with close-cropped gray hair, seemed to Helen to be unusually energetic for someone who was probably in her mid-sixties. Her name was Marta, and they learned that she was on sabbatical leave from her job as a professor of Social Sciences at Lund University in Sweden. She spoke rapidly, gesturing improbably with one of her walking poles. For several months she had been visiting colleagues at several universities in Europe as part of her ongoing research, and would be returning to Lund in time for the fall semester. Her academic consulting complete, a few days ago she had begun walking the Camino. She planned on continuing on to Santiago, taking her time along the way, but not so long that she couldn’t get back to the university in time for the new semester. Outgoing and direct, she had excellent English, and clearly was curious about them.

Bert filled her in on their basics, as he had practiced, taking pains to explain that they were not really a couple, but merely good friends. He said that they too had a deadline, but a far tighter one than hers, because each of them had to be back at work before running out of vacation time. He added that they might be able to walk in a more leisurely way when they retired, but neither of them had any plans to retire. When retirement became possible for them, in fact, they would probably opt to continue working.

Helen looked away so neither of them would notice her exasperated sigh. She wondered why he insisted on providing so much information to perfect strangers. In fact, she found it irksome.

“Ah, you are persons after my own heart! Is that the way you say it in America?”

“It sounds American enough to me,” said Bert.

“Well, I spent a good deal of time in America. Several times, maybe three years in all. I am also one of those persons for whom retirement is a foreign—maybe I should say forbidden—concept.”

“Welcome to the club. I think Helen likes her job a lot better than I like mine, probably because she actually gets to work out in nature some of the time. But even working in the city, I think what our agency is doing is worth the commitment. We’ll both probably stick with it as long as we are able.”

Their new companion did not reply immediately. They were walking along what looked like an old, unused farm road. It had paths worn in the dirt on either side of a row of weedy grasses. Short red flowers popped up here and there in the center patch. Helen followed Marta’s gaze to two horses, one brown and the other white, in the near distance across a barbed-wire fence to the left. The horses gave their full attention to grazing the tall, lush grasses and occasional red poppies in the pretty pasture. Helen wondered if the conversation was over, but after a while the woman continued.

“Maybe we really are not the same. I am different from you because it is not the nature of my work that keeps me from retiring. My work is all right, but of course there are always some problems. The academic world involves a good deal of politics, and I find much of it distasteful. I find some of the students easy to admire and to like, but as a group I do not find them sympathetic or interesting. Often they annoy me. And, after all these years my research no longer inspires me. It keeps me going, but does not pull me forward the way it once did. I am well known and respected in my field, and I do continue to enjoy the recognition I get from my colleagues in the international community of scholars. But lately even that has lost much of its luster. I must struggle to keep up. In my field, as in others as I suppose you know, one cannot simply glide along at the top because you are either struggling to stay ahead or falling behind.”

“Forgive me,” Helen said, trying to achieve a light-hearted tone, “but you sound like a walking, talking advertisement for retirement.”

“Oh, you don’t understand. I’m in a trap. My work is my life. I never intended it that way, but it happened. To give up my work will mean giving up my life, and if I weren’t working, there would be nothing. What would it be like to wake up each morning with nothing to plan and nothing to look forward to except the next meal or the next menial chore to be done?”

Marta’s words caused Helen to flash back to what Bert had said about peering into an abyss when the doctor told him he was fully recovered. She wondered how he reacted to what Marta said and was grateful she’d never felt that way.

“I think I’m extremely lucky, Marta,” she said. “I may be as dedicated to my profession and immersed in it as you are, but I’m fortunate in that my job with the Fish and Wildlife Service offers a continuous stream of new options and opportunities. Every job I’ve had has energized me and called me forward. I can’t see the end of the challenges and rewards.” She believed what she said, or at least wished her words to be true. But her optimistic statements seemed more than a bit hollow when she remembered being told she was on the fast track away from her perfect world at the refuge.

She expected Bert to support her comment, but he said nothing.

“I have a very dear friend,” Marta said. “What I just said about my career and my life I could not have told you if he had not shown it to me. He made me aware that I need to find more than my work if I am going to have a good life. It was he who encouraged me to try the Camino. Maybe you will find something there, he told me. Maybe you will discover some things missing from your life, or options that you have been denying. When you discover them it will free you from the captivity of your work.”

Helen overcame the urge to ask whether Marta had found any success, but Bert wasn’t so reluctant.

“I know it’s still early, but is the Camino working for you at all?” Bert asked. “Do you think you’ll find what you’ve been looking for?”

“No, not yet, but I have not given up hope. My hope is that by talking with people like you I will be able to acquire some of the wisdom that others have achieved in their own lives. It appears that neither of you have experienced the kind of crisis I am now facing, but still you have been helpful. I have learned from you that perhaps I have been too quick to feel I have achieved all I can in my career. Perhaps there is a way without retiring that I can build new things into my life based on past successes. I need to consider that possibility. But I am older than you and I worry that new career achievements may not be my right direction.”

They reached Villatuerta Puente and its café, and now Helen really was ready for coffee. Bert agreed it was time for a break. Marta said she would be walking on and thinking about their conversation.

“It seems that everyone I talk to along the trail has a different motivation and strategy. From you and from each of the others, I have learned and added new dimensions to my understanding of the human condition. That’s reason enough to walk the Camino,” Marta said waving goodbye.

When they each had a café con leche in hand, Bert returned to the conversation.

“That’s an interesting problem Marta is facing. Despite what we said, I suppose it’s something we could be looking at one of these days. Her problem wasn’t all that different from how I felt about my scary new lease on life.”

Helen didn’t like the drift of the conversation. She didn’t want to think about this. She couldn’t think of anything to say and just watched the ant walking across the table toward her cup.

“Marta’s problem isn’t just finding a hobby,” Bert went on, sipping his coffee. “From what she said, it’s about revisiting and reordering her life’s priorities. I sure don’t have an answer. Not for her, and not for me either. But it made me see my abyss differently somehow, I think.”

Helen didn’t want to tell Bert about the call from Donald and couldn’t think of a thing to say unless she did. She chose to let the topic drop. Bert was right, of course, but she rejected the idea of revisiting or reordering a life she had worked so hard to get to where it was. At any rate, retirement wasn’t an issue she would be addressing anytime soon. They sat in companionable silence as warm coffee and sticky, strawberry-filled pastries renewed their energy. Helen wondered aloud what Estella would be like, reminding Bert that in Iberia Michener had said it was his favorite Spanish city.

“As I recall,” said Bert, “Michener’s favorite towns were based heavily on the wines he sampled in them, and I don’t remember him saying he disliked any of them. Look at that dark cloud. It looks like we might get rained on.”

“I wonder if it ever rained on Michener,” Helen said as they hoisted their packs and returned to the trail. Before long they endured a few sprinkles.

Walking over another bridge, they crossed a river to enter the central historic district of Estella, where they would find their hostal. Bert said something about all the bridges they had crossed, and how they had not yet found one that would carry them over the abyss. She decided she wanted no part of that conversation.

The rain slacked off quickly, and they found and checked into the hostal. After a brief rest their curiosity about this Michener favorite drew them back out, blessedly pack-free, to take a drier look at Estella before dinner. Not much was happening because it was still siesta. Helen enjoyed the town nevertheless. Four- and five-story buildings of brick and stone surrounded the triangular plaza mayor, the town’s principal square, with its tiled surface, park benches, and pots of pink and red flowers. Above them loomed the tops of buildings on a streets built farther up on the hillside, and above all rose a rock outcrop topped by a large cross. Like much she had seen so far in Spain, the town didn’t look particularly planned, but was supremely adapted to accommodate people.

After dinner they noticed a stage where musicians were setting up large amplifiers, already surrounded by a crowd of flag-carrying people in the plaza mayor. Bert suggested it might be some kind of political rally. Despite the huge speakers surrounding the stage, she slept soundly. If any of the sound penetrated the thick stone walls of their hostal, she didn’t notice. Day Four had been exhausting.

“Despite everything, that was kind of fun,” said bleary-eyed Bert. “I didn’t come to Spain to sleep, so I guess I can’t claim to have been cheated.”

“Yeah, it wasn’t dull, and we have tales we can tell our friends. Plus we’ll have something to talk about if we bump into any of our bunkhouse fellows again. We’ll make some remark about how awful it was, and we’ll all have a good laugh together.”

“Wow! I have something in common with thirty people from the four corners of the earth! A bad night’s sleep! Ultreia!”

“I keep seeing and hearing that word,” said Helen. “Have you figured out what it means, exactly? It’s not in my dictionary.”

“Not really. But I think something like ‘onward’ or ‘keep it up’ is a good guess,” he replied. ”That fits the context of where I’ve seen it.”

“Good guess,” she said.

Helen indeed felt good as they left their Puente la Reina albergue and headed off on their way to Estella. They seemed to have left all rain behind. It was a sunny, cool morning. No jacket needed, just her tee-shirt with the long-sleeved shirt over it until it warmed up a bit. They walked down the narrow streets of the old town with Ilsa, who they’d met at the albergue. Coming up behind her, they recognized her at once by her long ponytail, blond and streaked with gray. She gave the same gold-and-silver impression from the front, with her fringe of blond hair and shining silver-gray eyes.

The twenty bunk beds in their basement room in the albergue had actually offered a tad of privacy because the beds were tucked into little cubicles. Ilsa was in the cubicle next to Bert and Helen. They all arrived at about the same time and went down into the dormitory together. Later they spotted her outside in the café-bar and asked if they could join her.

“I saw, when we all registered, that you’re from Australia,” Helen had said, sensing a companionable interlude. “It taxes my imagination to believe anyone comes all the way from Australia to hike the Camino!”

“Australia is so far from everywhere that many Australians, like me, prefer to get away on travel now and again. When you come to Europe, you do really want to stay a while. Walking the Camino is appealing because it isn’t being a tourist, it isn’t expensive, and it gives you time to think. I’m on winter break and walking by myself. I longed for some time to be really on my own, away from everything,” she said.

They had much in common and had spent a nice hour or so comparing career notes after they learned she taught zoology in Perth and she learned they were wildlife biologists. She hadn’t joined them at dinner but an interesting German couple did, and Helen enjoyed their company too.

Leaving Puente la Reina, the three of them crossed the namesake structure, a six-arch bridge built in the eleventh century to help pilgrims cross the Arga River. They each took photographs of the bridge and each other standing on it. Apparently preferring to walk alone, Ilsa bid them buen camino and headed off ahead on her own.

The countryside had a rugged aspect, but the trail was in very good shape—a wide clay path far from roads and traffic—and the walking was relatively easy. Vineyards and small wheat fields were tucked into the gentler slopes between the hills. The landscape was flooded with bright sunlight that gave it an almost luminescent quality.

Bert said he felt his body was, maybe, less resistant to the walking than it had been on the first two days. All wasn’t good, of course, and he went on to say something about a knee that wasn’t quite right and a sore back that he attributed to the sagging bunk in the albergue. Helen found herself still fussing with her pack, but only from time to time. It was riding better than on that hard first day. Another positive note was that her boots had mostly dried out, having been through stages of wetness, dampness, and near-dryness since the dunking they had taken on the way to Pamplona. They stopped in Mañeru for a rest and large cups of strong coffee, this time taken sin leche. This was not going to be a short day—nearly fourteen miles. Helen was inclined to stop and rest whenever the opportunity presented itself. Maybe resting often would be a way they could do this Camino after all, she thought.

A few miles beyond Mañeru they were overtaken and found themselves walking for a pleasant twenty minutes with the German couple they’d met at dinner the night before. Their names were Peter and Margot. They were walking alone, together, all the way from their home in Germany. Helen was pleased and realized she had begun to assemble her own little group of casual Camino friends. The thought that she and Bert might turn into the Friend Collectors Trudi and Heinrich was so absurd, it made her laugh to herself.

The conversation turned to rain gear. Peter remarked that their backpacks were still damp more than a day after they had experienced a torrential downpour approaching Zubiri. Finding no available lodging, they had been forced to walk on. They had worn waterproof jackets and put water repellant covers over their backpacks, but the driving rain had soaked the uncovered parts of their packs, including the shoulder straps and waist belt. Almost worse, it had dampened the inside of their packs—the parts that rested against their backs; water had cascaded off their hats and shoulders and invaded these spaces.

“We were lucky in two ways,” Bert said. “First, we had already settled into our hostal when the storm struck, and second, I received good advice about rain protection from the young man who sold me my pack. He said that most backpacks are not waterproof, and that he would gladly sell me a pack cover. He warned me about just what happened to you. He told me that the shower cap-like cover would protect only the back part of the pack, and the other parts, including the padded straps and waist belts would be vulnerable. Then he said he would happily sell me a slicker-like rain cape. A bit more expensive, it would cover pack and hiker, and provide unmatched protection from the rain.