|

Second Wind on the Way of St. James

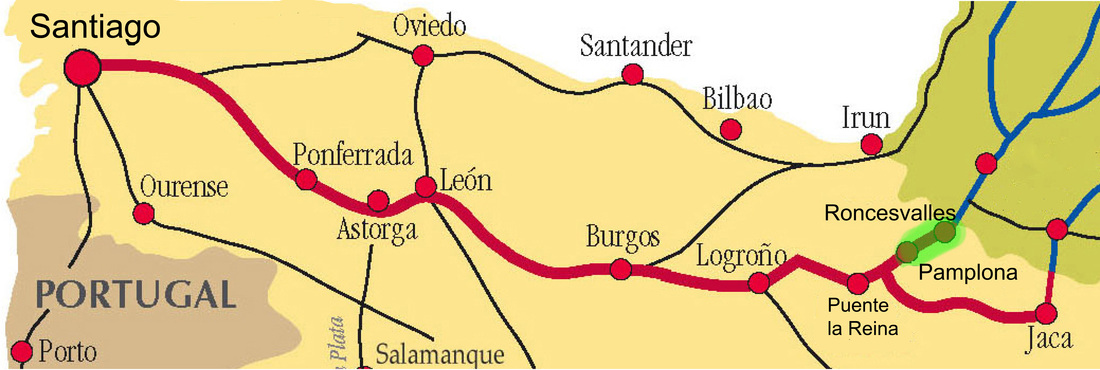

© 2013 by Russell J Hall and Peg Rooney Hall Published by: Lighthall Books P.O. Box 357305 Gainesville, Florida 32635-7305 http://www.lighthallbooks.com Orders: gem@lighthallbooks.com No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, either electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, except as specified by the authors. Electronic versions made available free of charge are intended for personal use, and may not be offered for sale in any form except by the authors. Excluded from copyright are the maps, which are based on the work of Manfred Zentgraf of Volkach, Germany. Like the original, our adaptations of his map remain in the public domain. Second Wind is a work of fiction. Many experiences of the authors on the Camino have inspired and informed themes of the book, but people and events depicted are products of the authors’ imaginations; any resemblance to real persons living or dead is purely coincidental. |

Acknowledgments We gratefully acknowledge the help and encouragement of Phyllis Hall Haislip, who read the manuscript with an author’s eye and with skills honed by writing and publishing many successful and award-winning books. We learned from her critiques and recommendations. This book is much better because of her. We also benefited greatly from the work of our editor Gaye Saucier Farris. Her corrections, comments, and suggestions, both on technical and artistic matters, helped immeasurably. Five years in the making, this project has been strengthened by many other people, especially Peggy Crevasse Ellison, who read parts of the manuscripts and provided comments and advice. We thank all of them, and also the veteran, novice, and want-to-be pilgrims we have met. They have taught us much, and in doing so they have contributed much to Second Wind. |

Episode 1

Prologue and First Steps

La Cruz de Ferro

Wednesday, June 16

Snarky conclusions? Virginal heights? I never should have thrown those words at her. I guess I’ve failed one more time at the relationship thing. She’s my best hope for figuring out the rest of my life, and I may have blown it. I should have kept my mouth shut.

He stuffed his sleeping bag into its sack, stowed the rest of his gear, hoisted the pack onto his back, and started toward the albergue’s porch to wait for Helen, who had showered after him.

Helen joined him without a word. Yesterday she had spotted a little place where she wanted to have breakfast, and the morning was still quite dark as they walked to it. Bert was not looking forward to their conversation.

Breakfast went better than he expected, however. He was surprised and relieved that she never brought it up. They talked about the day’s route. They drank their coffee and ate their tortillas españolas as if last night never happened. That was fine with him, and pretty much typical of them, he thought. Ignore the snags and after a while they sort of go away.

When they stepped out after breakfast, the sun was low and bright. Their shadows walked ahead of them on the trail, leading them across an open field.

The light was striking. It spilled like liquid gold across the panorama. A crumbling stone wall with an opening that used to be a window caught the light just ahead to their right. His eye followed the field down the hill to the left of the ruin and then up to the snowcapped mountains in the distance. He couldn’t remember ever having seen light like this before.

He expected following the trail up to the Cruz de Ferro to be a struggle, even without the snarky comments hanging over them. Their first miles of the day would bring them over the highest point on the Camino Francés—higher even than where it crosses the Pyrenees or at O’Cebreiro in the Cordillera Cantábrica. But the ascent was reasonably gentle. The golden light softened the edges of the climb, as well as of the scenery and his mood.

He began scanning the pine-covered horizon to the west, looking for the cross. Finally it appeared, perhaps a quarter of a mile ahead, a thin column over the treetops. The sun illuminated the scene like a floodlight with a pale gold filter.

A short distance beyond, they broke out of the curtain of trees that had been shielding the lower parts of the cross, and it suddenly came into full view. The tall wooden pole reached up out of a huge mound of rocks. It looked bronze in the morning’s light. Closer still, they were able to make out the namesake iron cross on the top of the pole. Colorful streamers and ribbons were attached to the lower part, as high as people could reach. The banners waved in a steady cool breeze, their blues, reds, and greens disrupting the yellow sun-drenched glow.

While still in the distance, they saw people climbing up on the rock pile to reach the base of the cross.

In his jacket pocket, Bert felt the crab apple-size stone he had picked up yesterday. How had they managed to walk almost three hundred and fifty miles and thirty days before learning of one of the most repeated bits of Camino lore? When they finally heard that people carry a stone symbolically loaded with their troubles and leave it at the iron cross, they’d each decided to give it a try. He loaded last night’s spat onto his.

He looked ahead at the huge rock pile. He liked the idea that it was made up of small stones carried up here by untold numbers of people. He fingered his stone thinking, ruefully, that it wasn’t so much the troubles of the past that he wanted to leave behind. Rather it was the troubles lying ahead—in the abyss—that weighed on him. Could adding a stone to the rock pile do anything about those troubles? Maybe he shouldn’t be leaving a stone on the pile, but instead taking one and keeping it with him until he had worked things out.

They reached the open, park-like area around the cross. People were climbing up singly or in groups. It was a major photo-op, and he guessed that few come away from the spot without a picture. Friends on the ground, or perhaps strangers pressed into service, clicked away. Atop the mound, some people looked joyful for the camera, while others placed their stones with quiet reverence.

He and Helen found a picnic table off to the side a bit. They sat next to each other, resting from the walk and taking in the scene. The Cruz de Ferro was not a place to rush by. They seemed to have decided this without even needing to discuss it.

Bert felt Helen’s attention on two men waiting to climb to the pole. The first went up, touched the pole, kissed his stone, placed it gently on the pile, and came back down with tears flowing on his ruddy cheeks. The second man stood with him a moment with an arm around his shoulder, then climbed to place his stone. Bert looked over to Helen and saw a tear in her eye. It made him want to put an arm around her. Instead he looked away, not wanting to embarrass her.

Soon they were ready to take their turns. Helen went up first. He got a good photo of her, arms outstretched, smiling broadly, short brown hair blowing in the wind. She looked triumphant and happy. Maybe she hadn’t taken last night’s words as seriously as he feared.

When it was his turn, he climbed the steep pile of loose rocks, feeling them slip under foot. Were other climbers this unsteady? As he reached the top and took out his stone, he noticed the many objects littering the place. Stones were in abundance, of course. Other mementos included messages written on the banners and streamers affixed to the pole, bits of paper wrapped with ribbons, a tiny teddy bear wearing glasses, and a stuffed angel named Jen, according to the tag on her wing. There was even a pack of cigarettes—a good burden to leave behind, he thought.

Ready to position his stone, he forced his stiff, reluctant body to bend over. Then he noticed something out of place, even in this eclectic mix. It looked like a wallet, and Bert’s first assumption was that it must have been dropped by one of the men they had just seen. If so, he could try to catch up with him and return it. Or he could leave it at an albergue, and the grapevine network might link it up with the owner.

He picked it up. It was plastic and seemed weather-beaten. Had it been out in the open for long, or was it just old and worn? Opening it, he found that it contained neither cash nor credit cards, but only a folded scrap of paper. Unfolding it, he read the words written in a large, shaky hand.

Peregrino

Solamente tú puedes salvar su propia vida

Ultreia!

He stared at the words, understanding their meaning almost at once, despite his rudimentary Spanish.

Was this message intended for him? How could that be? But it felt like it was. There was a lot of talk about the magic of the Camino, but he didn’t expect it would show itself like this.

And yet, as if magically, the message opened a door in his mind.

He had a fleeting thought that Helen might have left it for him to find. She had gone up before him. But her Spanish wasn’t good enough even for that simple message. And the style of the script had a definite European cast to it. Besides, it just didn’t seem like something she would say to him.

He looked at it again and then, looking toward the ground, saw others waiting to take their places on the rock pile. Folding the paper and sliding it into the wallet, he put it back where he had found it.

“What were you doing up there?” said Helen, when he was back on the ground.

He couldn’t imagine how to tell her what had changed. He was convinced she wouldn’t understand. “Oh, it was just that . . . something that looked like a wallet caught my eye. But it was something else. We can talk about it later . . . maybe by the time we get to Santiago. It’s hard to explain . . . really hard. And I’m ready to get walking again now.”

She didn’t press, which surprised him a little.

He wondered if he would find a way to explain it to her, even by the time they got to Santiago.

Putting on their backpacks, they retrieved their walking poles, and started along the wide path down from Monte Irago.

He stuffed his sleeping bag into its sack, stowed the rest of his gear, hoisted the pack onto his back, and started toward the albergue’s porch to wait for Helen, who had showered after him.

Helen joined him without a word. Yesterday she had spotted a little place where she wanted to have breakfast, and the morning was still quite dark as they walked to it. Bert was not looking forward to their conversation.

Breakfast went better than he expected, however. He was surprised and relieved that she never brought it up. They talked about the day’s route. They drank their coffee and ate their tortillas españolas as if last night never happened. That was fine with him, and pretty much typical of them, he thought. Ignore the snags and after a while they sort of go away.

When they stepped out after breakfast, the sun was low and bright. Their shadows walked ahead of them on the trail, leading them across an open field.

The light was striking. It spilled like liquid gold across the panorama. A crumbling stone wall with an opening that used to be a window caught the light just ahead to their right. His eye followed the field down the hill to the left of the ruin and then up to the snowcapped mountains in the distance. He couldn’t remember ever having seen light like this before.

He expected following the trail up to the Cruz de Ferro to be a struggle, even without the snarky comments hanging over them. Their first miles of the day would bring them over the highest point on the Camino Francés—higher even than where it crosses the Pyrenees or at O’Cebreiro in the Cordillera Cantábrica. But the ascent was reasonably gentle. The golden light softened the edges of the climb, as well as of the scenery and his mood.

He began scanning the pine-covered horizon to the west, looking for the cross. Finally it appeared, perhaps a quarter of a mile ahead, a thin column over the treetops. The sun illuminated the scene like a floodlight with a pale gold filter.

A short distance beyond, they broke out of the curtain of trees that had been shielding the lower parts of the cross, and it suddenly came into full view. The tall wooden pole reached up out of a huge mound of rocks. It looked bronze in the morning’s light. Closer still, they were able to make out the namesake iron cross on the top of the pole. Colorful streamers and ribbons were attached to the lower part, as high as people could reach. The banners waved in a steady cool breeze, their blues, reds, and greens disrupting the yellow sun-drenched glow.

While still in the distance, they saw people climbing up on the rock pile to reach the base of the cross.

In his jacket pocket, Bert felt the crab apple-size stone he had picked up yesterday. How had they managed to walk almost three hundred and fifty miles and thirty days before learning of one of the most repeated bits of Camino lore? When they finally heard that people carry a stone symbolically loaded with their troubles and leave it at the iron cross, they’d each decided to give it a try. He loaded last night’s spat onto his.

He looked ahead at the huge rock pile. He liked the idea that it was made up of small stones carried up here by untold numbers of people. He fingered his stone thinking, ruefully, that it wasn’t so much the troubles of the past that he wanted to leave behind. Rather it was the troubles lying ahead—in the abyss—that weighed on him. Could adding a stone to the rock pile do anything about those troubles? Maybe he shouldn’t be leaving a stone on the pile, but instead taking one and keeping it with him until he had worked things out.

They reached the open, park-like area around the cross. People were climbing up singly or in groups. It was a major photo-op, and he guessed that few come away from the spot without a picture. Friends on the ground, or perhaps strangers pressed into service, clicked away. Atop the mound, some people looked joyful for the camera, while others placed their stones with quiet reverence.

He and Helen found a picnic table off to the side a bit. They sat next to each other, resting from the walk and taking in the scene. The Cruz de Ferro was not a place to rush by. They seemed to have decided this without even needing to discuss it.

Bert felt Helen’s attention on two men waiting to climb to the pole. The first went up, touched the pole, kissed his stone, placed it gently on the pile, and came back down with tears flowing on his ruddy cheeks. The second man stood with him a moment with an arm around his shoulder, then climbed to place his stone. Bert looked over to Helen and saw a tear in her eye. It made him want to put an arm around her. Instead he looked away, not wanting to embarrass her.

Soon they were ready to take their turns. Helen went up first. He got a good photo of her, arms outstretched, smiling broadly, short brown hair blowing in the wind. She looked triumphant and happy. Maybe she hadn’t taken last night’s words as seriously as he feared.

When it was his turn, he climbed the steep pile of loose rocks, feeling them slip under foot. Were other climbers this unsteady? As he reached the top and took out his stone, he noticed the many objects littering the place. Stones were in abundance, of course. Other mementos included messages written on the banners and streamers affixed to the pole, bits of paper wrapped with ribbons, a tiny teddy bear wearing glasses, and a stuffed angel named Jen, according to the tag on her wing. There was even a pack of cigarettes—a good burden to leave behind, he thought.

Ready to position his stone, he forced his stiff, reluctant body to bend over. Then he noticed something out of place, even in this eclectic mix. It looked like a wallet, and Bert’s first assumption was that it must have been dropped by one of the men they had just seen. If so, he could try to catch up with him and return it. Or he could leave it at an albergue, and the grapevine network might link it up with the owner.

He picked it up. It was plastic and seemed weather-beaten. Had it been out in the open for long, or was it just old and worn? Opening it, he found that it contained neither cash nor credit cards, but only a folded scrap of paper. Unfolding it, he read the words written in a large, shaky hand.

Peregrino

Solamente tú puedes salvar su propia vida

Ultreia!

He stared at the words, understanding their meaning almost at once, despite his rudimentary Spanish.

Was this message intended for him? How could that be? But it felt like it was. There was a lot of talk about the magic of the Camino, but he didn’t expect it would show itself like this.

And yet, as if magically, the message opened a door in his mind.

He had a fleeting thought that Helen might have left it for him to find. She had gone up before him. But her Spanish wasn’t good enough even for that simple message. And the style of the script had a definite European cast to it. Besides, it just didn’t seem like something she would say to him.

He looked at it again and then, looking toward the ground, saw others waiting to take their places on the rock pile. Folding the paper and sliding it into the wallet, he put it back where he had found it.

“What were you doing up there?” said Helen, when he was back on the ground.

He couldn’t imagine how to tell her what had changed. He was convinced she wouldn’t understand. “Oh, it was just that . . . something that looked like a wallet caught my eye. But it was something else. We can talk about it later . . . maybe by the time we get to Santiago. It’s hard to explain . . . really hard. And I’m ready to get walking again now.”

She didn’t press, which surprised him a little.

He wondered if he would find a way to explain it to her, even by the time they got to Santiago.

Putting on their backpacks, they retrieved their walking poles, and started along the wide path down from Monte Irago.

Months Earlier

Sandpine Key, Florida

January

She knew she was clutching the phone too tightly. He answered before the third ring. She was sitting in the overstuffed reading chair next to her bed, where she’d plopped down and picked up the phone the minute she got home. She hadn’t even waited to get out of her uniform. The dogs were hovering, probably wondering why they hadn’t gotten their usual after-work treats.

“Well, Bert, how’d it go?” The meeting with his cardiologist had been much anticipated.

“I don’t have to go back for six months. Practically a clean bill of health. He said I’m good to go for most normal activities. Of course I might want to think twice before climbing Mt. Everest or attempting a triathlon. He even said he thinks I’m in better shape than lots of men my age who haven’t had heart problems.”

She let herself breathe again.

“Fantastic! You must feel like a huge weight has been lifted.”

“It’s kind of amazing. My life changed for the worse in an eye blink when the aneurism showed up. Then it changed back again with a few words from a doctor. Things are almost back where they were a year and a half ago. . . Where are you? I hear the dogs.”

“I’m home. Just got here.” She wondered where Bert was and how he looked, not having seen him since he got sick. She imagined him as she’d last seen him on a bright sunlight afternoon with a brisk breeze―sitting tall and lean at the bar table on his back deck, dark hair, trim matching beard with a tad of gray at the sideburns, blue eyes darting after flitting warblers even as he talked to her. The image didn’t fit on a January day in Maryland, she thought. She wondered if he lost much weight through all this. His frame wasn’t so large that he needed to weigh a lot, but he was too tall to drop to 160 or she feared, even less.

“Bert, I am so glad. You must feel great.”

“Funny, but I had a strange mix of feelings. It was completely unexpected. I was leaving the office, and Dr. Webster said now I could get on with living the rest of my life. That was disturbing. After months of thinking about nothing but my touch-and-go heart situation, all of a sudden I have to worry about what to do with the rest of my life! I know I’ll go back to work full-time. But it struck me—it still strikes me—that I have no plans for the rest of my life. Here I am. A doctor just handed me the rest of my life, and I have no inkling of what to do with it.”

“Don’t look at the dark side, Bert. This is a good news day for you. Take my word for it. We’ve been waiting for this for a long time. Enjoy it. I’ll call you in a few days and remind you in case you forget to be happy about it.”

Glancing up at the mirror over the dresser, she noticed a strand of hair out of place and pushed it behind her ear. It was still brown, but now was getting too long. She’d need to schedule an appointment soon.

__________

It was perhaps two hours later when, preparing to make herself a fried egg sandwich for supper, she recalled a conversation she had with Jeanne, a colleague from a Virginia refuge. They were at a training session at the National Conservation Training Center in West Virginia. Jeanne had said something about how the previous summer she and her husband had walked most of a 500-mile trail in Spain. Helen reached for the phone.

“Jeanne, that walk you told me about… You really walked 500 miles? You were kidding, right?” Helen said when her friend picked up the phone. “If that’s not crazy, at least it seems like a very odd vacation—especially at our age.”

Jeanne laughed. “Well, hello to you too, Helen. And how are things going at the North Pass National Wildlife Refuge? All is well here in Virginia. And, oh yes, about the Camino . . . It wasn’t exactly crazy, and it wasn’t quite a vacation. But, it was doing after fifty what I never would have dreamed of doing in my twenties.”

Helen returned Jeanne’s laugh. The idea of doing something at this stage in her life that would have seemed too challenging even decades ago was intriguing.

They chatted a bit more, their conversation bouncing around between that walk in Spain and recent events. Jeanne’s final words before the call ended were, “The Camino changed our lives.”

Those words lodged in Helen’s mind as her eggs sizzled in the pan.

Maybe that was what Bert needed—a life-changing experience.

__________

They heard the truck pull into the driveway. Helen was home. Ears raised, heads cocked, they were on alert. It was three days later.

“We’re off for a hike, best friends! I have more good news to share. This time it’s about me, not Bert. I can hardly believe it happened in the same week.”

She was already half out of her brown uniform shirt when she reached the bedroom and grabbed her shorts and Tee-shirt from the closet hook. A minute later, they were jumping in the front seat of the pickup beside her. She pointed the truck toward their special-hike trail. On the way, she gave them the news.

“I got a call about two hours ago from the Friends of Refuges Society. I’ve been named Refuge Manager of the Year. I’m embarrassed to say I blurted out, ‘How could that be!’ I never should have done that. I hope I didn’t sound as unprofessional to her as I did to me.”

All three of them jumped down into the parking lot, and the dogs waited for Helen to clip on their leashes. Then they turned toward the three-mile loop trail that goes down into a hammock, around a big sinkhole, and up the other side. Like furry bumper cars, the dogs darted off together, trying to surround a bush, one going to each side to scare out whatever was hiding. They pulled her along, barely avoiding a dense thicket of yaupon holly, enjoying the unusual outing and reflecting her excitement. It always amused her to watch them together in the woods. Who would think the two breeds would be a woods-sniffing team?

Helen continued her story. They tried to be attentive, in their springer and dachshund ways.

“What a thrill! I feel like I just hit the sky. The community gets visibility, the refuge gets recognition, and I do too. I love this job. I love being responsible for what happens and doesn’t happen in this place. This is why I’m in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This is why I’ve worked so hard. This is why I haven’t needed to take any vacation days in more than two years. This makes a difference. I am one happy refuge manager! Wahoo! I need to find some special way to celebrate.”

Only her four-legged friends and Bert would hear that version. She couldn’t wait to call him.

__________

Saturday, January 15 10:12 AM

To: helen.morgia@southnet.com

From: bchaz@hometown.net

Subject: Bravo

Helen,

I am so happy about your award! It was great to talk with you. I don’t think I came close to saying on the phone how pleased I am that they selected you. You deserve it and more. What excellent news. It has certainly been a good week for us, my friend.

Bert

__________

The Camino just wouldn’t let go of Helen’s brain. The more she thought about what Jeanne told her about the trek, the less crazy—even strangely appealing—it seemed. Maybe she’d really like to do it too. And, what a special way that would be to celebrate her award!

Finally, she decided to stop toying with the idea and figure out what she would need to do to make it happen. She e-mailed back and forth with Jeanne, getting details and becoming more and more convinced that this was the adventure-filled celebration she wanted. And she knew it would be good for Bert. Now to recruit him to the challenge.

__________

Friday, January 28 6:10 PM

To: bchaz@hometown.net

From: helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Talk tomorrow?

I’m calling you at noon tomorrow, if that works for you. I may need an hour because I plan to talk you into doing something neither of us ever would have dreamed of doing in a million years.

Helen

__________

Bert was even more shocked by the idea than had Helen expected.

After weeks of thinking about the Camino and e-mailing with Jeanne, Helen was well into a planning mode. It was difficult to remember the mental journey that had overcome her initial hesitation.

Bert reacted the way Helen had at first, and was stuck there. She got no vibes from him of intrigue or curiosity. She worried that he might actually not come around.

“Helen, hello! This is your friend, Bert, who just spent months of his life training his heart to work right again. You want me to walk five hundred miles—across a whole country—for adventure? What are you thinking?”

His response took her aback. She couldn’t think of what to say.

“Well . . . I told you when I e-mailed . . . it was something neither of us would ever have dreamed of doing in an entire lifetime,” she tried.

“I think you’re nuts. A great friend, but nuts. Honestly, Helen, you were right―I not only would never have dreamed of doing that in a million years, but in a million years, you could never talk me into doing it.”

Helen swallowed and caught her breath. She was certainly not going to push it after that comment.

“Okay, I hear you Bert. When Jeanne first told me about it, I had a milder version of your reaction. So, I kind of understand. But what happened with me was that the image of doing it just stuck to me and grew more and more intriguing. If Jeanne could do it, why not me? Please will you give the idea a chance? Please will you not push away any little glimmer of appeal that pokes at you about the possibility?

“I cannot imagine that will happen, Helen. But I promise if it does, I will hold an open mind, like a good scientist trying not to shut out other hypotheses.”

As he said it, she heard his voice drop back down to its normal low, light tone from the high intensity it had when he responded initially.

“If you can bring yourself to do it, take a look at the website of the American Pilgrims on the Camino, Bert,” she said. “It has an amazing amount of data. I’ll continue to hold onto a tiny hope that data will turn your head where my description of the adventure failed to do so.”

“Okay, Helen. We’ll talk in a few days.”

“Well, Bert, how’d it go?” The meeting with his cardiologist had been much anticipated.

“I don’t have to go back for six months. Practically a clean bill of health. He said I’m good to go for most normal activities. Of course I might want to think twice before climbing Mt. Everest or attempting a triathlon. He even said he thinks I’m in better shape than lots of men my age who haven’t had heart problems.”

She let herself breathe again.

“Fantastic! You must feel like a huge weight has been lifted.”

“It’s kind of amazing. My life changed for the worse in an eye blink when the aneurism showed up. Then it changed back again with a few words from a doctor. Things are almost back where they were a year and a half ago. . . Where are you? I hear the dogs.”

“I’m home. Just got here.” She wondered where Bert was and how he looked, not having seen him since he got sick. She imagined him as she’d last seen him on a bright sunlight afternoon with a brisk breeze―sitting tall and lean at the bar table on his back deck, dark hair, trim matching beard with a tad of gray at the sideburns, blue eyes darting after flitting warblers even as he talked to her. The image didn’t fit on a January day in Maryland, she thought. She wondered if he lost much weight through all this. His frame wasn’t so large that he needed to weigh a lot, but he was too tall to drop to 160 or she feared, even less.

“Bert, I am so glad. You must feel great.”

“Funny, but I had a strange mix of feelings. It was completely unexpected. I was leaving the office, and Dr. Webster said now I could get on with living the rest of my life. That was disturbing. After months of thinking about nothing but my touch-and-go heart situation, all of a sudden I have to worry about what to do with the rest of my life! I know I’ll go back to work full-time. But it struck me—it still strikes me—that I have no plans for the rest of my life. Here I am. A doctor just handed me the rest of my life, and I have no inkling of what to do with it.”

“Don’t look at the dark side, Bert. This is a good news day for you. Take my word for it. We’ve been waiting for this for a long time. Enjoy it. I’ll call you in a few days and remind you in case you forget to be happy about it.”

Glancing up at the mirror over the dresser, she noticed a strand of hair out of place and pushed it behind her ear. It was still brown, but now was getting too long. She’d need to schedule an appointment soon.

__________

It was perhaps two hours later when, preparing to make herself a fried egg sandwich for supper, she recalled a conversation she had with Jeanne, a colleague from a Virginia refuge. They were at a training session at the National Conservation Training Center in West Virginia. Jeanne had said something about how the previous summer she and her husband had walked most of a 500-mile trail in Spain. Helen reached for the phone.

“Jeanne, that walk you told me about… You really walked 500 miles? You were kidding, right?” Helen said when her friend picked up the phone. “If that’s not crazy, at least it seems like a very odd vacation—especially at our age.”

Jeanne laughed. “Well, hello to you too, Helen. And how are things going at the North Pass National Wildlife Refuge? All is well here in Virginia. And, oh yes, about the Camino . . . It wasn’t exactly crazy, and it wasn’t quite a vacation. But, it was doing after fifty what I never would have dreamed of doing in my twenties.”

Helen returned Jeanne’s laugh. The idea of doing something at this stage in her life that would have seemed too challenging even decades ago was intriguing.

They chatted a bit more, their conversation bouncing around between that walk in Spain and recent events. Jeanne’s final words before the call ended were, “The Camino changed our lives.”

Those words lodged in Helen’s mind as her eggs sizzled in the pan.

Maybe that was what Bert needed—a life-changing experience.

__________

They heard the truck pull into the driveway. Helen was home. Ears raised, heads cocked, they were on alert. It was three days later.

“We’re off for a hike, best friends! I have more good news to share. This time it’s about me, not Bert. I can hardly believe it happened in the same week.”

She was already half out of her brown uniform shirt when she reached the bedroom and grabbed her shorts and Tee-shirt from the closet hook. A minute later, they were jumping in the front seat of the pickup beside her. She pointed the truck toward their special-hike trail. On the way, she gave them the news.

“I got a call about two hours ago from the Friends of Refuges Society. I’ve been named Refuge Manager of the Year. I’m embarrassed to say I blurted out, ‘How could that be!’ I never should have done that. I hope I didn’t sound as unprofessional to her as I did to me.”

All three of them jumped down into the parking lot, and the dogs waited for Helen to clip on their leashes. Then they turned toward the three-mile loop trail that goes down into a hammock, around a big sinkhole, and up the other side. Like furry bumper cars, the dogs darted off together, trying to surround a bush, one going to each side to scare out whatever was hiding. They pulled her along, barely avoiding a dense thicket of yaupon holly, enjoying the unusual outing and reflecting her excitement. It always amused her to watch them together in the woods. Who would think the two breeds would be a woods-sniffing team?

Helen continued her story. They tried to be attentive, in their springer and dachshund ways.

“What a thrill! I feel like I just hit the sky. The community gets visibility, the refuge gets recognition, and I do too. I love this job. I love being responsible for what happens and doesn’t happen in this place. This is why I’m in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This is why I’ve worked so hard. This is why I haven’t needed to take any vacation days in more than two years. This makes a difference. I am one happy refuge manager! Wahoo! I need to find some special way to celebrate.”

Only her four-legged friends and Bert would hear that version. She couldn’t wait to call him.

__________

Saturday, January 15 10:12 AM

To: helen.morgia@southnet.com

From: bchaz@hometown.net

Subject: Bravo

Helen,

I am so happy about your award! It was great to talk with you. I don’t think I came close to saying on the phone how pleased I am that they selected you. You deserve it and more. What excellent news. It has certainly been a good week for us, my friend.

Bert

__________

The Camino just wouldn’t let go of Helen’s brain. The more she thought about what Jeanne told her about the trek, the less crazy—even strangely appealing—it seemed. Maybe she’d really like to do it too. And, what a special way that would be to celebrate her award!

Finally, she decided to stop toying with the idea and figure out what she would need to do to make it happen. She e-mailed back and forth with Jeanne, getting details and becoming more and more convinced that this was the adventure-filled celebration she wanted. And she knew it would be good for Bert. Now to recruit him to the challenge.

__________

Friday, January 28 6:10 PM

To: bchaz@hometown.net

From: helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Talk tomorrow?

I’m calling you at noon tomorrow, if that works for you. I may need an hour because I plan to talk you into doing something neither of us ever would have dreamed of doing in a million years.

Helen

__________

Bert was even more shocked by the idea than had Helen expected.

After weeks of thinking about the Camino and e-mailing with Jeanne, Helen was well into a planning mode. It was difficult to remember the mental journey that had overcome her initial hesitation.

Bert reacted the way Helen had at first, and was stuck there. She got no vibes from him of intrigue or curiosity. She worried that he might actually not come around.

“Helen, hello! This is your friend, Bert, who just spent months of his life training his heart to work right again. You want me to walk five hundred miles—across a whole country—for adventure? What are you thinking?”

His response took her aback. She couldn’t think of what to say.

“Well . . . I told you when I e-mailed . . . it was something neither of us would ever have dreamed of doing in an entire lifetime,” she tried.

“I think you’re nuts. A great friend, but nuts. Honestly, Helen, you were right―I not only would never have dreamed of doing that in a million years, but in a million years, you could never talk me into doing it.”

Helen swallowed and caught her breath. She was certainly not going to push it after that comment.

“Okay, I hear you Bert. When Jeanne first told me about it, I had a milder version of your reaction. So, I kind of understand. But what happened with me was that the image of doing it just stuck to me and grew more and more intriguing. If Jeanne could do it, why not me? Please will you give the idea a chance? Please will you not push away any little glimmer of appeal that pokes at you about the possibility?

“I cannot imagine that will happen, Helen. But I promise if it does, I will hold an open mind, like a good scientist trying not to shut out other hypotheses.”

As he said it, she heard his voice drop back down to its normal low, light tone from the high intensity it had when he responded initially.

“If you can bring yourself to do it, take a look at the website of the American Pilgrims on the Camino, Bert,” she said. “It has an amazing amount of data. I’ll continue to hold onto a tiny hope that data will turn your head where my description of the adventure failed to do so.”

“Okay, Helen. We’ll talk in a few days.”

February

Helen hoped Bert would come around, and was not just stalling and putting off giving her a final refusal. He called on Wednesday evening just as she and the dogs returned from their after-work walk.

Always as good as his word, he had read through the website.

“Even for an analytical research guy like me, it had a lot of information,” Bert admitted. “Now I have a much richer appreciation of how crazy this idea of yours is.”

Then he moved to a new tack―from talking her out of the idea, to suggesting he was not the right person to go with her. He was too old to sleep in dormitories with bunk beds. Just the thought of carrying a backpack made his legs hurt. Why not find someone who really wanted to do this and would match her own enthusiasm?

“You’re coming around, Bert,” said Helen. “You just don’t know it yet. I hear you asking the same questions I did before deciding I wanted to do it. Talk to them at your next rehab session, just to be sure. I bet after that you’ll be ready to say yes.”

“Not likely,” he replied. “But okay. I’ll call you on the weekend so you’ll have plenty of time to find somebody else to go with you.”

__________

He called Saturday morning. “Well, drat,” he began. “My rehab coach had actually heard of the Camino before and wasted no time in telling me I should do it.”

“Hurrah!” Helen was pleased. She could picture his eyes smiling at her reaction, but also knew his “Drat” was not fully in jest. “Tell me more,” she said. “He didn’t just say go for it, did he?”

“No,” said Bert. "He actually said that he thought there wasn’t much more he could do for me. So, the training to get ready and then the walking itself could be just what was needed to put me totally back at the top of my game, so to speak. These rehab types are way too into sports analogies for me,” he complained.

“I’d be better off than most other hikers having worked so hard at my fitness over the past months,” he told me. "Then he added that almost no one dies of exhaustion on the trail. He thought that was funnier than I did.”

“Bert, I am so happy to hear all that. What do you think? Will you consider going with me?”

“I really don’t share your enthusiasm for the challenge,” he replied. “And there is a sticking point I cannot see a way around.”

“I’m listening. I hope I can see the way around,” she said.

“Okay, here it is. The Camino is a pilgrim trail. I can’t imagine you on a pilgrimage. More to the point, given how contentedly unchurched I am, I could never be a pilgrim, Helen.”

“Oh dear, that’s a problem that I too have found almost impossible to deal with. I don‘t think I can be a pilgrim, either. But from what Jeanne told me, it’s not a really a churchy thing. I decided that would have to be enough for me because I so want to try it.”

“Well, it just isn’t enough for me. I can’t be a fake pilgrim for five hundred miles. Let me see what I can learn about the facts of Jeanne’s claim.”

“Thanks Bert, that would be good for both of us.”

__________

Wednesday, February 9 9:13 PM

To: helen.morgia@southnet.com

From: bchaz@hometown.net

Subject: Pilgrims…Not

Helen,

Finally I found some information to address our problem.

Pretending to be a pilgrim was an insurmountable barrier for me. I now see that neither of us would have to do that. Unfortunately this means I may be free to agree to your invitation.

It turns out that, based on its origin, the word pilgrim had a far less restrictive meaning in the beginning than it does currently. The Latin root is commonly translated as ‘foreigners’ or ‘wanderers.’ It is not difficult to see how the name might be applied to strangers showing up in northern Spain in the Middle Ages. Eventually it came to refer not to just any strangers, but specifically to those walking to Santiago.

Well, okay, I can be a wanderer with you, a stranger, or a foreigner. I’ll agree to come if you agree never to call me a pilgrim.

Bert

__________

She picked up the phone impulsively the minute she saw his e-mail on her laptop as she was having her morning coffee.

“Yes! Let the adventure begin,” she said when he answered. “Hope I didn’t wake you, Bert, but I just had to call. I went to bed early and didn’t see your message until right now.”

“No, you didn’t wake me. And, I am glad that since I have agreed to come, reluctant though I am, you are pleased to have me along,” he said.

“Thanks Bert. I really wanted to take on this adventure, and to take it on with you. I’ll design us a training schedule and start thinking about what else we need. Talk to you soon.”

__________

They e-mailed and talked on the phone all through the spring, trading impressions about their training and comparing notes on buying all the gear they would need.

Shortly before it was time for them to leave, Helen received another unexpected phone call in the office.

Always as good as his word, he had read through the website.

“Even for an analytical research guy like me, it had a lot of information,” Bert admitted. “Now I have a much richer appreciation of how crazy this idea of yours is.”

Then he moved to a new tack―from talking her out of the idea, to suggesting he was not the right person to go with her. He was too old to sleep in dormitories with bunk beds. Just the thought of carrying a backpack made his legs hurt. Why not find someone who really wanted to do this and would match her own enthusiasm?

“You’re coming around, Bert,” said Helen. “You just don’t know it yet. I hear you asking the same questions I did before deciding I wanted to do it. Talk to them at your next rehab session, just to be sure. I bet after that you’ll be ready to say yes.”

“Not likely,” he replied. “But okay. I’ll call you on the weekend so you’ll have plenty of time to find somebody else to go with you.”

__________

He called Saturday morning. “Well, drat,” he began. “My rehab coach had actually heard of the Camino before and wasted no time in telling me I should do it.”

“Hurrah!” Helen was pleased. She could picture his eyes smiling at her reaction, but also knew his “Drat” was not fully in jest. “Tell me more,” she said. “He didn’t just say go for it, did he?”

“No,” said Bert. "He actually said that he thought there wasn’t much more he could do for me. So, the training to get ready and then the walking itself could be just what was needed to put me totally back at the top of my game, so to speak. These rehab types are way too into sports analogies for me,” he complained.

“I’d be better off than most other hikers having worked so hard at my fitness over the past months,” he told me. "Then he added that almost no one dies of exhaustion on the trail. He thought that was funnier than I did.”

“Bert, I am so happy to hear all that. What do you think? Will you consider going with me?”

“I really don’t share your enthusiasm for the challenge,” he replied. “And there is a sticking point I cannot see a way around.”

“I’m listening. I hope I can see the way around,” she said.

“Okay, here it is. The Camino is a pilgrim trail. I can’t imagine you on a pilgrimage. More to the point, given how contentedly unchurched I am, I could never be a pilgrim, Helen.”

“Oh dear, that’s a problem that I too have found almost impossible to deal with. I don‘t think I can be a pilgrim, either. But from what Jeanne told me, it’s not a really a churchy thing. I decided that would have to be enough for me because I so want to try it.”

“Well, it just isn’t enough for me. I can’t be a fake pilgrim for five hundred miles. Let me see what I can learn about the facts of Jeanne’s claim.”

“Thanks Bert, that would be good for both of us.”

__________

Wednesday, February 9 9:13 PM

To: helen.morgia@southnet.com

From: bchaz@hometown.net

Subject: Pilgrims…Not

Helen,

Finally I found some information to address our problem.

Pretending to be a pilgrim was an insurmountable barrier for me. I now see that neither of us would have to do that. Unfortunately this means I may be free to agree to your invitation.

It turns out that, based on its origin, the word pilgrim had a far less restrictive meaning in the beginning than it does currently. The Latin root is commonly translated as ‘foreigners’ or ‘wanderers.’ It is not difficult to see how the name might be applied to strangers showing up in northern Spain in the Middle Ages. Eventually it came to refer not to just any strangers, but specifically to those walking to Santiago.

Well, okay, I can be a wanderer with you, a stranger, or a foreigner. I’ll agree to come if you agree never to call me a pilgrim.

Bert

__________

She picked up the phone impulsively the minute she saw his e-mail on her laptop as she was having her morning coffee.

“Yes! Let the adventure begin,” she said when he answered. “Hope I didn’t wake you, Bert, but I just had to call. I went to bed early and didn’t see your message until right now.”

“No, you didn’t wake me. And, I am glad that since I have agreed to come, reluctant though I am, you are pleased to have me along,” he said.

“Thanks Bert. I really wanted to take on this adventure, and to take it on with you. I’ll design us a training schedule and start thinking about what else we need. Talk to you soon.”

__________

They e-mailed and talked on the phone all through the spring, trading impressions about their training and comparing notes on buying all the gear they would need.

Shortly before it was time for them to leave, Helen received another unexpected phone call in the office.

April

“Helen, this is Donald.”

She had met the Assistant Director only once, but knew right away who he was. Use of first names was the norm in the organization.

“Congratulations on getting the Refuge Manager of the Year Award. Headquarters couldn’t be more pleased that you are the one they recognized this year. We wanted to wait until after the ceremony and official conferring of the honor before calling you about it. But, we have all been talking about how you’ve done an amazing job at North Pass Refuge.”

“Thank you,” she replied weakly.

“This really puts you on the fast track. You have a lot to contribute, and we’re thinking that we need you back to Washington to provide policy and oversight guidance for all the refuges. I don’t know just what the position will be or when. I know you have scheduled some well-deserved leave time. Sooner rather than later after you return from your trip would be our target. Start packing. Well, not really, just know how excited we are to get you up here with us.”

That was all he said. She momentarily felt good to be considered valuable to the whole Refuge System. It was another affirmation of her hard work and success. She responded cautiously again with a professional thank you.

The minute she hung up she knew the news couldn’t be worse. She’d spent her whole life working to get to where she was now. Being the refuge manager was hands-on, in the field, make-it-happen work. She was in charge. The refuge was her own little world. If something broke, she fixed it. If opportunity arose, she grabbed it. Her life was exactly what she wanted it to be. Moving to the Washington Office would ruin everything. She couldn’t tell the dogs. She wouldn’t tell Bert. She was in celebration mode. She resolved to forget the call happened, at least until after the Camino.

She had met the Assistant Director only once, but knew right away who he was. Use of first names was the norm in the organization.

“Congratulations on getting the Refuge Manager of the Year Award. Headquarters couldn’t be more pleased that you are the one they recognized this year. We wanted to wait until after the ceremony and official conferring of the honor before calling you about it. But, we have all been talking about how you’ve done an amazing job at North Pass Refuge.”

“Thank you,” she replied weakly.

“This really puts you on the fast track. You have a lot to contribute, and we’re thinking that we need you back to Washington to provide policy and oversight guidance for all the refuges. I don’t know just what the position will be or when. I know you have scheduled some well-deserved leave time. Sooner rather than later after you return from your trip would be our target. Start packing. Well, not really, just know how excited we are to get you up here with us.”

That was all he said. She momentarily felt good to be considered valuable to the whole Refuge System. It was another affirmation of her hard work and success. She responded cautiously again with a professional thank you.

The minute she hung up she knew the news couldn’t be worse. She’d spent her whole life working to get to where she was now. Being the refuge manager was hands-on, in the field, make-it-happen work. She was in charge. The refuge was her own little world. If something broke, she fixed it. If opportunity arose, she grabbed it. Her life was exactly what she wanted it to be. Moving to the Washington Office would ruin everything. She couldn’t tell the dogs. She wouldn’t tell Bert. She was in celebration mode. She resolved to forget the call happened, at least until after the Camino.

May

Wednesday, May 11, 11:51 AM

To: helen.morgia@southnet.com

From: bchaz@hometown.net

Subject: Being Ready

Dear Helen,

In our first conversation about this crazy idea of yours, you suggested that even if we never went, it would be good to do the training. I have to admit that you were right about that. I’m feeling better about my physical strength than I have in two years. For that I thank you.

Now can we forget about really doing the Camino and just go hang out on a beach in Costa Rica for a month? Friday the 13th is no day to begin an adventure, for crying out loud! B

____________

Thursday, May 12, 3:22 PM

To: bchaz@hometown.net

From: helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Re: Being Ready

Hell no, Old Man. I’m just back from a 12-miler and I am not wasting this woman power on a beach. I’ll meet you at the gate at Dulles tomorrow. Don’t worry. I’ll make sure it is Saturday the 14th when we arrive in Spain. The time has come. We are off to the Camino. Fate is calling.

Helen

To: helen.morgia@southnet.com

From: bchaz@hometown.net

Subject: Being Ready

Dear Helen,

In our first conversation about this crazy idea of yours, you suggested that even if we never went, it would be good to do the training. I have to admit that you were right about that. I’m feeling better about my physical strength than I have in two years. For that I thank you.

Now can we forget about really doing the Camino and just go hang out on a beach in Costa Rica for a month? Friday the 13th is no day to begin an adventure, for crying out loud! B

____________

Thursday, May 12, 3:22 PM

To: bchaz@hometown.net

From: helen.morgia@southnet.com

Subject: Re: Being Ready

Hell no, Old Man. I’m just back from a 12-miler and I am not wasting this woman power on a beach. I’ll meet you at the gate at Dulles tomorrow. Don’t worry. I’ll make sure it is Saturday the 14th when we arrive in Spain. The time has come. We are off to the Camino. Fate is calling.

Helen

Dulles International Airport

Friday, May 13

Bert had taken an airport limousine so as not to leave his car parked at Dulles for almost two months. He had come early so he would be there when Helen arrived on her flight from Florida. Waiting by her arrival gate, he wondered why he had bothered to come early to keep her company for the couple of hours before the flight to Madrid. After all, they’d be together constantly for weeks once they got there.

He couldn’t believe he was doing this. How had she talked him into it?

He watched all the people scurrying by to catch flights, or pacing around to ward off boredom while waiting for them. He thought about how, despite the give and take that preceded his decision to do it and the months of training, finding himself actually on his way to Spain seemed disconcerting. Now events were in charge, and like all these other travelers, he would probably have little or no opportunity to control what happened.

Perhaps he had given her too hard a time in his protracted reluctance to come along with her on this adventure. His health concerns had been real enough. Two summers ago he and Helen were at her camp in Orebed Lake in the Adirondacks. He was at the old Orebed Mine looking over a ledge to try to spot whether some loons were nesting below. He fell, far and hard. At the tiny ten-bed hospital in town, the doctors told him that although he recovered well from the immediate effects of the fall, such a massive trauma might cause an aneurism to form. Indeed he was among the unlucky for whom that was true. It helped that having been forewarned, he had monitored his condition.

After the fright and his lengthy recovery, the idea of walking for two months did not sit comfortably. In the end he’d decided that the experience might indeed do him some good, although right now he couldn’t imagine how or why. Perhaps because it was so different from anything he’d done before, it felt like a first step into the abyss Dr. Webster’s words had opened before him.

He wondered how many of these other people were traveling today only because someone asked them to do it. After her being such a good friend through his recovery, his lack of enthusiasm for the venture had left him with a twinge of guilt. He could see why she wanted to do something so extraordinary as a way of congratulating herself for getting the award. Being named Refuge Manager of the Year was no small feat, he knew. Still, this whole trip was very unlike her. He wondered if there might be more to this Camino thing of hers.

He looked around again at all the travelers moving about. He felt himself becoming part of that other-worldly travel zone where nothing is real except that you are completely at the mercy of the system. Maybe his dislike for travel had fed his reluctance. He remembered one of the moments that changed his mind. She had said something about how she didn’t know why she wanted to celebrate by walking the Camino, but she knew she wanted to take it on. And, she had added in a very uncharacteristically personal comment—she wanted to take it on with him. He could picture her big dark brown eyes as she spoke into the phone. Thinking of them reminded him of that long-ago weekend when it seemed possible a flame could ignite. It didn’t happen then. A few times since when their eyes had met, he had renewed hope that something might be there for them. But it was her saying she wanted to take on the Camino with him that sent a warm, familiar surge of blood through his chest. It rushed in like adrenalin and his resistance collapsed. Still, it troubled him that things would almost certainly go awry, as they had in the past.

He checked his Blackberry for the time. Automatically he looked to see if he had any e-mails. Of course, he didn’t. It was only Friday, his first day of vacation, and nobody was likely to need him yet.

He half-heard an announcement that could have been her flight’s arrival. Looking at the message board, he saw that her plane had landed.

He scanned the cluster of people coming through the arrival gate, and didn’t see her. Of course, she was no taller than five and a half feet, he guessed, and wouldn’t stand out in the crowd entering the gate area. Indeed, she was well out into the arrival lounge before she appeared from behind a group of other passengers.

Had he forgotten what a great looking woman she was? Or perhaps, the aneurism had done something to his vision. Already, in May, her face was tanned, and he realized that he was quite pale by comparison. She had obviously been spending more time outdoors than him.

Helen’s dark eyes, her whole expression when she spotted him watching her, showed a mixture of pleasure, shock, and puzzlement. Then a little smile appeared on her face.

“You shaved off your beard!”

He rubbed his chin and smiled back at her. “Yeah, I wore the thing for twenty-five years. About a year ago I realized I didn’t like the color. It had decided to turn gray. Of course, after I shaved the gray beard the rest of my hair began turning. I imagine the beard would be almost white now, so I’m in no hurry to let it grow back. But you, my friend, you don’t seem to have a single gray hair. And your brown locks are shorter, but they haven’t gotten straight or begun to fall out. Of course I could be mistaken. Maybe you just have an uncommonly talented hairdresser.”

“Well, grayer hair and all, you look good too, but it might be hard to get used to that half-naked face of yours. Glad you kept the mustache. Without the beard your face is more angular and square-jawed, but you haven’t lost too much weight with all that rehab.”

Bert would have liked her to notice the compliment about her dark hair, but he settled for her thinking he looked good after the long illness.

They swung their backpacks on and headed for the international gates. “You look remarkably fit and trim,” he said. “In those boots, you might even be able to walk five hundred miles.”

“And I plan to do just that. After all our training, maybe I’ll skip the whole way.”

Some of his worry about this adventure faded under the spell of her enthusiasm. As they walked in the stream of passengers moving between gates, and were bombarded by the noise, tension, boredom, and cinnamon aroma omnipresent in airport terminals, he looked at her again and realized that he didn’t know how old Helen was. He’d always assumed they were about the same age, but he wasn’t sure. If she were also in her fifties, she had definitely managed to stay youthful. Her weight was right and she looked strong. As refuge manager, he guessed she walked on dirt roads, mowed fields, tossed around bales of straw, as well as desk-jockeying all the phone calls with the public. Maybe that was it, maybe it wasn’t her physical features, but instead her vitality that came across when he looked at her. She did look good. He hadn’t exactly forgotten it, but it was good to be reminded again how her smile warmed him.

He thought they must be quite fashionable. Neither was a clothes horse. But they had both enjoyed shopping for their hiking garb. He was wearing his dark gray titanium hiking pants—the kind with zip-off legs that convert them to shorts. Even with all their hidden pockets and their self-belt, they fitted his well-trained body. His long-sleeved Tee-shirt was also a quick-dry synthetic material and more fitted than he would usually choose a shirt. But with all his rehab and training, he felt he looked good in it. After all, he was heading off on a hike, not going to an office party. The airport was typically cold so he also had on his ultra-lightweight jacket. It hung loosely on his shoulders for layering over an extra shirt on really cold days. Had he been more attuned to apparel, he would have noted that it matched his blue eyes.

Helen looked even better in her hiking clothes than he felt in his. Like his, her outfit had no hint of slow-to-dry cotton. She too was one hundred percent synthetic material. Instead of a Tee-shirt, she was wearing a short-sleeved one with a collar. Her dark green jacket and convertible pants skimmed over her toned shape. He recalled a passage in a memoir about the Camino Helen had sent him. The author, a Canadian woman, had complained that stylish hiking clothes simply weren’t available. Her idea of stylish sure differs from mine, he thought. He and Helen were dressing up to take to the trails, unlike that author, who lamented having to dress down.

They arrived at their gate and settled in for the two-hour wait. He was comfortable to be in her company again and quietly terrified by what they were about to take on.

He looked at the time on his Blackberry every now and then. Before long, it was time to begin boarding. Once they were seated, he liked feeling her shoulder next to his on the shared arm rest.

The long flight went as planned, and they arrived in Madrid before the sun came up.

Their first task was to ascertain that their checked bag arrived with them. Bert had packed a small duffel with his and Helen’s walking poles, scissors, jackknife, and a month-long supply of shampoos and other liquids that couldn’t be brought into the cabin. They’d brought all the other gear they could in their backpacks to limit what they’d have to replace if their checked duffel didn’t make it.

“There it is,” she called out. “I claim its arrival as a good omen for the trip.”

He too was relieved when it appeared on the carousel. He grabbed it and they headed for the shuttle bus to the RENFE station, where they would get their train to Pamplona.

“The bus leaves in twenty minutes,” he said. “I can’t believe I’m doing this, but here we are, and the coming disaster has yet to reveal itself.”

The shuttle bus took them to the Atocha station where they got a high-speed train to Pamplona and then a bus to Roncesvalles. Bert watched Helen fall asleep. He checked his Blackberry and noted it had updated itself to Spanish time. Of course he had no e-mails. He felt himself nodding off, oblivious to the Spanish landscape rolling by.

He couldn’t believe he was doing this. How had she talked him into it?

He watched all the people scurrying by to catch flights, or pacing around to ward off boredom while waiting for them. He thought about how, despite the give and take that preceded his decision to do it and the months of training, finding himself actually on his way to Spain seemed disconcerting. Now events were in charge, and like all these other travelers, he would probably have little or no opportunity to control what happened.

Perhaps he had given her too hard a time in his protracted reluctance to come along with her on this adventure. His health concerns had been real enough. Two summers ago he and Helen were at her camp in Orebed Lake in the Adirondacks. He was at the old Orebed Mine looking over a ledge to try to spot whether some loons were nesting below. He fell, far and hard. At the tiny ten-bed hospital in town, the doctors told him that although he recovered well from the immediate effects of the fall, such a massive trauma might cause an aneurism to form. Indeed he was among the unlucky for whom that was true. It helped that having been forewarned, he had monitored his condition.

After the fright and his lengthy recovery, the idea of walking for two months did not sit comfortably. In the end he’d decided that the experience might indeed do him some good, although right now he couldn’t imagine how or why. Perhaps because it was so different from anything he’d done before, it felt like a first step into the abyss Dr. Webster’s words had opened before him.

He wondered how many of these other people were traveling today only because someone asked them to do it. After her being such a good friend through his recovery, his lack of enthusiasm for the venture had left him with a twinge of guilt. He could see why she wanted to do something so extraordinary as a way of congratulating herself for getting the award. Being named Refuge Manager of the Year was no small feat, he knew. Still, this whole trip was very unlike her. He wondered if there might be more to this Camino thing of hers.

He looked around again at all the travelers moving about. He felt himself becoming part of that other-worldly travel zone where nothing is real except that you are completely at the mercy of the system. Maybe his dislike for travel had fed his reluctance. He remembered one of the moments that changed his mind. She had said something about how she didn’t know why she wanted to celebrate by walking the Camino, but she knew she wanted to take it on. And, she had added in a very uncharacteristically personal comment—she wanted to take it on with him. He could picture her big dark brown eyes as she spoke into the phone. Thinking of them reminded him of that long-ago weekend when it seemed possible a flame could ignite. It didn’t happen then. A few times since when their eyes had met, he had renewed hope that something might be there for them. But it was her saying she wanted to take on the Camino with him that sent a warm, familiar surge of blood through his chest. It rushed in like adrenalin and his resistance collapsed. Still, it troubled him that things would almost certainly go awry, as they had in the past.

He checked his Blackberry for the time. Automatically he looked to see if he had any e-mails. Of course, he didn’t. It was only Friday, his first day of vacation, and nobody was likely to need him yet.

He half-heard an announcement that could have been her flight’s arrival. Looking at the message board, he saw that her plane had landed.

He scanned the cluster of people coming through the arrival gate, and didn’t see her. Of course, she was no taller than five and a half feet, he guessed, and wouldn’t stand out in the crowd entering the gate area. Indeed, she was well out into the arrival lounge before she appeared from behind a group of other passengers.

Had he forgotten what a great looking woman she was? Or perhaps, the aneurism had done something to his vision. Already, in May, her face was tanned, and he realized that he was quite pale by comparison. She had obviously been spending more time outdoors than him.

Helen’s dark eyes, her whole expression when she spotted him watching her, showed a mixture of pleasure, shock, and puzzlement. Then a little smile appeared on her face.

“You shaved off your beard!”

He rubbed his chin and smiled back at her. “Yeah, I wore the thing for twenty-five years. About a year ago I realized I didn’t like the color. It had decided to turn gray. Of course, after I shaved the gray beard the rest of my hair began turning. I imagine the beard would be almost white now, so I’m in no hurry to let it grow back. But you, my friend, you don’t seem to have a single gray hair. And your brown locks are shorter, but they haven’t gotten straight or begun to fall out. Of course I could be mistaken. Maybe you just have an uncommonly talented hairdresser.”

“Well, grayer hair and all, you look good too, but it might be hard to get used to that half-naked face of yours. Glad you kept the mustache. Without the beard your face is more angular and square-jawed, but you haven’t lost too much weight with all that rehab.”

Bert would have liked her to notice the compliment about her dark hair, but he settled for her thinking he looked good after the long illness.

They swung their backpacks on and headed for the international gates. “You look remarkably fit and trim,” he said. “In those boots, you might even be able to walk five hundred miles.”

“And I plan to do just that. After all our training, maybe I’ll skip the whole way.”

Some of his worry about this adventure faded under the spell of her enthusiasm. As they walked in the stream of passengers moving between gates, and were bombarded by the noise, tension, boredom, and cinnamon aroma omnipresent in airport terminals, he looked at her again and realized that he didn’t know how old Helen was. He’d always assumed they were about the same age, but he wasn’t sure. If she were also in her fifties, she had definitely managed to stay youthful. Her weight was right and she looked strong. As refuge manager, he guessed she walked on dirt roads, mowed fields, tossed around bales of straw, as well as desk-jockeying all the phone calls with the public. Maybe that was it, maybe it wasn’t her physical features, but instead her vitality that came across when he looked at her. She did look good. He hadn’t exactly forgotten it, but it was good to be reminded again how her smile warmed him.

He thought they must be quite fashionable. Neither was a clothes horse. But they had both enjoyed shopping for their hiking garb. He was wearing his dark gray titanium hiking pants—the kind with zip-off legs that convert them to shorts. Even with all their hidden pockets and their self-belt, they fitted his well-trained body. His long-sleeved Tee-shirt was also a quick-dry synthetic material and more fitted than he would usually choose a shirt. But with all his rehab and training, he felt he looked good in it. After all, he was heading off on a hike, not going to an office party. The airport was typically cold so he also had on his ultra-lightweight jacket. It hung loosely on his shoulders for layering over an extra shirt on really cold days. Had he been more attuned to apparel, he would have noted that it matched his blue eyes.

Helen looked even better in her hiking clothes than he felt in his. Like his, her outfit had no hint of slow-to-dry cotton. She too was one hundred percent synthetic material. Instead of a Tee-shirt, she was wearing a short-sleeved one with a collar. Her dark green jacket and convertible pants skimmed over her toned shape. He recalled a passage in a memoir about the Camino Helen had sent him. The author, a Canadian woman, had complained that stylish hiking clothes simply weren’t available. Her idea of stylish sure differs from mine, he thought. He and Helen were dressing up to take to the trails, unlike that author, who lamented having to dress down.

They arrived at their gate and settled in for the two-hour wait. He was comfortable to be in her company again and quietly terrified by what they were about to take on.

He looked at the time on his Blackberry every now and then. Before long, it was time to begin boarding. Once they were seated, he liked feeling her shoulder next to his on the shared arm rest.

The long flight went as planned, and they arrived in Madrid before the sun came up.

Their first task was to ascertain that their checked bag arrived with them. Bert had packed a small duffel with his and Helen’s walking poles, scissors, jackknife, and a month-long supply of shampoos and other liquids that couldn’t be brought into the cabin. They’d brought all the other gear they could in their backpacks to limit what they’d have to replace if their checked duffel didn’t make it.

“There it is,” she called out. “I claim its arrival as a good omen for the trip.”

He too was relieved when it appeared on the carousel. He grabbed it and they headed for the shuttle bus to the RENFE station, where they would get their train to Pamplona.

“The bus leaves in twenty minutes,” he said. “I can’t believe I’m doing this, but here we are, and the coming disaster has yet to reveal itself.”

The shuttle bus took them to the Atocha station where they got a high-speed train to Pamplona and then a bus to Roncesvalles. Bert watched Helen fall asleep. He checked his Blackberry and noted it had updated itself to Spanish time. Of course he had no e-mails. He felt himself nodding off, oblivious to the Spanish landscape rolling by.

Stage One: First Steps

Roncesvalles to Pamplona

The Journey Begins

Roncesvalles

Saturday, May 14

The monastery wasn’t at all what Bert expected. They passed through the heavy wooden doors and entered the massive stone building. Stepping into a long hallway flanked by plush couches and antique furnishings, they were bathed in indirect light from modernistic lamps. The warm glow and rich mosaic flooring nicely balanced the rough stone walls and crude wood beams of the ceiling. The charm was unmistakable and almost overwhelming. Clearly the place had been remodeled to serve the needs of the present rather than restored to preserve a remnant of the past. His idea of what a monastery should look or feel like was cold, dank, cramped. He was pleased by its failure to be any of those things.

Following posted instructions, they paid and got their room key at the bar of the nearby Casa Sabina, one of the town’s two restaurants. Roncesvalles was tiny. They had gotten off the bus in a daze, having slept only sitting up and only briefly in the past thirty-some hours. Taking in Roncesvalles, they noted it seemed to consist of only about six or seven buildings mostly on the right side of the road. Those in the monastery complex, uphill on the right, were quite large. They had walked no more than a few dozen yards up the road from the bus stop to the monastery, then backtracked a bit to get the key, then back to the monastery.

Reaching their room by elevator, Bert found that it perfectly fit his recently upgraded expectations, being as pleasant and comfortable-looking as the downstairs common rooms. Bright indirect lighting, rough stone walls softened by plush mahogany-color drapes, twin beds, a sitting room with overstuffed chairs, a small kitchen area with microwave oven, warm radiators, and plenty of space where they could organize their gear. In the bathroom he noticed the thick white towels on heated racks, and thought at once that those racks would be put to good use after they finished washing the clothes they’d worn for the past two days of traveling.

“Let’s not tell any of our friends what this place is really like,” said Helen. “Let’s just say we stayed in an old monastery. They can think we were stuffed into tiny cubicles with iron cots and horsehair mattresses.”

”I won’t let on. It would spoil everything for them. Let them imagine us enduring all sorts of medieval discomfort.”

Helen had booked them into the monastery on the advice of Jeanne, who told her that Roncesvalles was said to have a new albergue, but advised that the monastery better fit what they would need to recover from their travel. Bert was thankful for the advice. This night at least, he wasn’t ready for all the coughing, snoring, and wandering around at night he’d heard are common in the albergues.

Exhausted and nearly numb after two days of airports, planes, trains, and buses, Bert felt as if the adventure should be nearly over. Helen appeared to be in no better shape than he was, although she had slept on the transatlantic flight, and he had not. Even on the train from Madrid to Pamplona, he doubted he had slept for more than an hour or so.

When they were settled in, Bert checked the time on his phone. It was already time to go back to the Casa Sabina for dinner. A table was set up inside the door and a young woman was stamping pilgrim passports. Bert had ordered theirs from the American Pilgrims on the Camino just after Helen had booked their plane tickets. Helen had learned from Jeanne that in addition to your official passport, you needed a pilgrim passport. Each overnight accommodation, as well as some churches and other landmarks along the Camino, stamps and dates the passport with a uniquely designed rubber stamp to provide a record of a walker’s progress. Brought to the pilgrim office in Santiago, the passport is examined by officials to assure the bearer has walked at least the final one hundred kilometers and qualifies for the official certificate of completion, the Compostela.

Bert and Helen got their first stamps and then Bert went to the bar and paid ten euros each for their dinner. He was happy he had gotten a hundred dollars’ worth of euros before leaving home; nothing in Roncesvalles resembled a bank. He had suggested and she agreed that they would take turns paying for meals. They queued up, waiting for the doors to the dining room to be opened. When they got in, a woman led them to a four-person table in a corner where they were joined by a young woman. The room was bright, with red and white checkered tablecloths and curtains, and it echoed with the friendly buzz of conversations in several languages. When all were seated, Bert guessed that this must be his lucky day. The three of them sat at a table with bread and a bottle of wine set up for four. Feeling famished after not having had a real meal in days, he savored the thought of sharing an extra portion of bread and also looked forward to an extra portion of wine.

Their table-mate introduced herself as Maria. She appeared to be in her thirties, was attractive in an understated way with short dark hair framing a round face and a smile that came more from her brown eyes than her small mouth. Her English was only slightly accented. She explained that she was a provincial government scientist from Mexico on a leave of absence. She was walking alone, and had begun walking the day before, across the French border in the town of Saint Jean Pied de Port.